Benedict of Nursia was a Christian saint venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, the Anglican Communion and Old Catholic Churches. He is a patron saint of Europe.

A sundial is a horological device that tells the time of day when direct sunlight shines by the apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the word, it consists of a flat plate and a gnomon, which casts a shadow onto the dial. As the Sun appears to move through the sky, the shadow aligns with different hour-lines, which are marked on the dial to indicate the time of day. The style is the time-telling edge of the gnomon, though a single point or nodus may be used. The gnomon casts a broad shadow; the shadow of the style shows the time. The gnomon may be a rod, wire, or elaborately decorated metal casting. The style must be parallel to the axis of the Earth's rotation for the sundial to be accurate throughout the year. The style's angle from horizontal is equal to the sundial's geographical latitude.

A diptych is any object with two flat plates which form a pair, often attached by hinge. For example, the standard notebook and school exercise book of the ancient world was a diptych consisting of a pair of such plates that contained a recessed space filled with wax. Writing was accomplished by scratching the wax surface with a stylus. When the notes were no longer needed, the wax could be slightly heated and then smoothed to allow reuse. Ordinary versions had wooden frames, but more luxurious diptychs were crafted with more expensive materials.

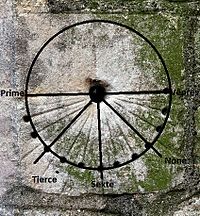

In the practice of Christianity, canonical hours mark the divisions of the day in terms of fixed times of prayer at regular intervals. A book of hours, chiefly a breviary, normally contains a version of, or selection from, such prayers.

Matins is a canonical hour in Christian liturgy, originally sung during the darkness of early morning.

The Bewcastle Cross is an Anglo-Saxon cross which is still in its original position within the churchyard of St Cuthbert's church at Bewcastle, in the English county of Cumbria. The cross, which probably dates from the 7th or early 8th century, features reliefs and inscriptions in the runic alphabet. The head of the cross is missing but the remains are 14.5 feet high, and almost square in section 22 × 21¼ inches at the base. The crosses of Bewcastle and Ruthwell have been described by the scholar Nikolaus Pevsner as "the greatest achievement of their date in the whole of Europe".

Nones, also known as None, the Ninth Hour, or the Midafternoon Prayer, is a fixed time of prayer of the Divine Office of almost all the traditional Christian liturgies. It consists mainly of psalms and is said around 3 pm, about the ninth hour after dawn.

Sext, or Sixth Hour, is a canonical hour of the Divine Office of almost all the traditional Christian liturgies. It consists mainly of psalms and is held around noon. Its name comes from Latin and refers to the sixth hour of the day after dawn. With Terce, None and Compline it belongs to the so-called "Little hours".

Bewcastle is a large civil parish in the City of Carlisle district of Cumbria, England. It is in the historic county of Cumberland.

Analemmatic sundials are a type of horizontal sundial that has a vertical gnomon and hour markers positioned in an elliptical pattern. The gnomon is not fixed and must change position daily to accurately indicate time of day. Hence there are no hour lines on the dial and the time of day is read only on the ellipse. As with most sundials, analemmatic sundials mark solar time rather than clock time.

St Michael and All Angels Church stands on Warhill overlooking the village of Mottram in Longdendale, Greater Manchester, England. The church is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II* listed building. It is an active Anglican parish church in the diocese of Chester, the archdeaconry of Macclesfield and the deanery of Mottram.

Nendrum Monastery was a Christian monastery on Mahee Island in Strangford Lough, County Down, Northern Ireland. Medieval records say it was founded in the 5th century, but this is uncertain. The monastery came to an end at some time between 974 and 1178, but its church served a parish until the site was abandoned in the 15th century. Some remains of the monastery can still be seen.

A sundial is a device that indicates time by using a light spot or shadow cast by the position of the Sun on a reference scale. As the Earth turns on its polar axis, the sun appears to cross the sky from east to west, rising at sun-rise from beneath the horizon to a zenith at mid-day and falling again behind the horizon at sunset. Both the azimuth (direction) and the altitude (height) can be used to create time measuring devices. Sundials have been invented independently in every major culture and became more accurate and sophisticated as the culture developed.

Sundial, Boy With Spider is an outdoor sculpture and functional sundial by American artist Willard Dryden Paddock (1873–1956). It is located within the Oldfields estate on the grounds of the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA), in Indianapolis, Indiana, United States. The bronze sculpture, cast by the Gorham Manufacturing Company, depicts a boy sitting cross-legged with an open scroll in his lap.

All Saints Church is a redundant Anglican church in the village of Little Wenham, Suffolk, England. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building, and is under the care of the Churches Conservation Trust. It stands in an isolated position close to Little Wenham Hall, about 0.6 miles (1 km) to the northwest of Capel St. Mary.

The Whitehurst & Son sundial was produced in Derby in 1812 by the nephew of John Whitehurst. It is a fine example of a precision sundial telling local apparent time with a scale to convert this to local mean time, and is accurate to the nearest minute. The sundial is now housed in the Derby Museum and Art Gallery.

St John's Church is situated on the south bank of the River Esk in the hamlet of Hall Waberthwaite in the former civil parish of Waberthwaite, Cumbria, England. It is an active Anglican parish church in the deanery of Calder, the archdeaconry of West Cumberland, and the diocese of Carlisle. Its benefice is united with those of St Paul, Irton; St Michael, Muncaster; and St Catherine, Boot. The church is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II* listed building.

A London dial in the broadest sense can mean any sundial that is set for 51°30′ N, but more specifically refers to a engraved brass horizontal sundial with a distinctive design. London dials were originally engraved by scientific instrument makers. The trade was heavily protected by the system of craft guilds.

A schema for horizontal dials is a set of instructions used to construct horizontal sundials using compass and straightedge construction techniques, which were widely used in Europe from the late fifteenth century to the late nineteenth century. The common horizontal sundial is a geometric projection of an equatorial sundial onto a horizontal plane.

Clone Church is a Romanesque medieval church and National Monument in County Wexford, Ireland.