Cryptic coloration and camouflage

Timema walking sticks are night-feeders who spend daytime resting on the leaves or bark of the plants they feed on. Timema colors (primarily green, gray, or brown) and patterns (which may be stripes, scales, or dots) match their typical background, a form of crypsis. [7] [8]

In 2008, researchers studying the presence or absence of a dorsal stripe suggested that it has independently evolved several times in Timema species and is an adaptation for crypsis on needle-like leaves. All of the eight Timema species with a dorsal stripe have at least one host plant with needle-like foliage. Of the thirteen unstriped species, seven feed only on broadleaf plants. Four (T. ritense, T. podura, T. genevievae, and T. coffmani) rest during the day on the host plant's trunk rather than its leaves and have bodies that are brown, gray, or tan. Only two species (T. nakipa and T. boharti) have green unstriped morphs that feed on needle-like foliage; both are generalist feeders that also feed on broadleaf hosts. [7]

The species Timema cristinae exhibits both striped and unstriped populations depending on the host plant, a form of polymorphism that clearly illustrates the camouflage function of the stripe. [7] The earliest ancestors of this species were generalists that fed on plants belonging to both the genera Adenostoma and Ceanothus . They eventually diverged into two distinct ecotypes with a more specialist host plant preference. One ecotype prefers to feed on Adenostoma while the other ecotype prefers to feed on Ceanothus. The Adenostoma ecotype possesses a white dorsal stripe, an adaptation to blend in with the needle-like leaves of the plant, while the Ceanothus ecotype does not (Ceanothus spp. have broad leaves). The Adenostoma ecotype is also smaller, with a wider head, and shorter legs. [9]

These characteristics are genetically inherited and has been interpreted as the early stages of the speciation process. The two ecotypes will eventually become separate species once reproductive isolation is achieved. At the moment, both ecotypes are still capable of interbreeding and producing viable offspring, as such they are still considered a single species. [9] [10]

Life cycle and reproduction

Timema eggs are soft, ellipsoidal, and about two mm long, with a lid-like structure at one end (the operculum) through which the nymph will emerge. [11] Timema females use particles of dirt, which they have previously ingested, to coat their eggs. [12]

The eggs of many stick insects, including Timema, are attractive to ants, who carry them away to their burrows to feed on the egg's capitulum, while leaving the rest of the egg intact to hatch. [13] [14] The emerging nymph passes through six or seven instars before reaching adulthood. [14]

Timema males, in sexual species of Timema, show a consistent pattern of courting behavior. The male climbs onto the back of the female and, after a short display of vibrating and waving, they proceed to mate. (Rejection by the female is possible but uncommon.) The male then rides on the female's back for up to five days, a behavior often referred to as "guarding" the female. [15]

Several species of Timema are parthenogenetic: [16] that is, females can reproduce asexually, producing viable eggs without male participation.

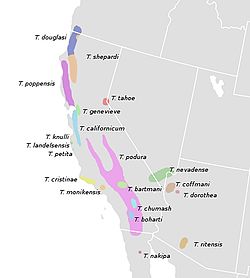

According to Tanja Schwander, "Timema are indeed the oldest insects for which there is good evidence that they have been asexual for long periods of time." [5] She heads a team of researchers who found that five Timema species (T. douglasi, T. monikense, T. shepardi, T. tahoe and T. genevievae) have used only asexual reproduction for more than 500,000 years, with T. tahoe and T. genevievae reproducing asexually for over one million years. [5] [17]

Genetic analysis, published in 2023, of four asexual Timema species suggested that males, which are rare but not entirely absent, do in fact engage in sexual reproduction with some females. [18]