A catalytic converter is an exhaust emission control device which converts toxic gases and pollutants in exhaust gas from an internal combustion engine into less-toxic pollutants by catalyzing a redox reaction. Catalytic converters are usually used with internal combustion engines fueled by gasoline or diesel, including lean-burn engines, and sometimes on kerosene heaters and stoves.

Vehicle emissions control is the study of reducing the emissions produced by motor vehicles, especially internal combustion engines. The primary emissions studied include hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and sulfur oxides. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, various regulatory agencies were formed with a primary focus on studying the vehicle emissions and their effects on human health and the environment. As the worlds understanding of vehicle emissions improved, so did the devices used to mitigate their impacts. The regulatory requirements of the Clean Air Act, which was amended many times, greatly restricted acceptable vehicle emissions. With the restrictions, vehicles started being designed more efficiently by utilizing various emission control systems and devices which became more common in vehicles over time.

Exhaust gas or flue gas is emitted as a result of the combustion of fuels such as natural gas, gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, fuel oil, biodiesel blends, or coal. According to the type of engine, it is discharged into the atmosphere through an exhaust pipe, flue gas stack, or propelling nozzle. It often disperses downwind in a pattern called an exhaust plume.

Selective catalytic reduction (SCR) means of converting nitrogen oxides, also referred to as NO

x with the aid of a catalyst into diatomic nitrogen, and water. A reductant, typically anhydrous ammonia, aqueous ammonia, or a urea solution, is added to a stream of flue or exhaust gas and is reacted onto a catalyst. As the reaction drives toward completion, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide, in the case of urea use, are produced.

The New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) was a driving cycle, last updated in 1997, designed to assess the emission levels of car engines and fuel economy in passenger cars. It is also referred to as MVEG cycle.

Diesel exhaust fluid is a liquid used to reduce the amount of air pollution created by a diesel engine. Specifically, DEF is an aqueous urea solution made with 32.5% urea and 67.5% deionized water. DEF is consumed in a selective catalytic reduction (SCR) that lowers the concentration of nitrogen oxides in the diesel exhaust emissions from a diesel engine.

A driving cycle is a series of data points representing the speed of a vehicle versus time.

The European emission standards are vehicle emission standards for pollution from the use of new land surface vehicles sold in the European Union and European Economic Area member states and the United Kingdom, and ships in EU waters. The standards are defined in a series of European Union directives staging the progressive introduction of increasingly stringent standards.

The fuel economy of an automobile relates to the distance traveled by a vehicle and the amount of fuel consumed. Consumption can be expressed in terms of the volume of fuel to travel a distance, or the distance traveled per unit volume of fuel consumed. Since fuel consumption of vehicles is a significant factor in air pollution, and since the importation of motor fuel can be a large part of a nation's foreign trade, many countries impose requirements for fuel economy.

A portable emissions measurement system (PEMS) is a vehicle emissions testing device that is small and light enough to be carried inside or moved with a motor vehicle that is being driven during testing, rather than on the stationary rollers of a dynamometer that only simulates real-world driving.

The Not-To-Exceed (NTE) standard promulgated by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) ensures that heavy-duty truck engine emissions are controlled over the full range of speed and load combinations commonly experienced in use. NTE establishes an area under the torque curve of an engine where emissions must not exceed a specified value for any of the regulated pollutants. The NTE test procedure does not involve a specific driving cycle of any specific length. Rather it involves driving of any type that could occur within the bounds of the NTE control area, including operation under steady-state or transient conditions and under varying ambient conditions. Emissions are averaged over a minimum time of thirty seconds and then compared to the applicable NTE emission limits.

United States vehicle emission standards are set through a combination of legislative mandates enacted by Congress through Clean Air Act (CAA) amendments from 1970 onwards, and executive regulations managed nationally by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and more recently along with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). These standards cover tailpipe pollution, including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate emissions, and newer versions have incorporated fuel economy standards. However they lag behind European emission standards, which limit air pollution from brakes and tires.

Bharat stage emission standards (BSES) are emission standards instituted by the Government of India to regulate the output of air pollutants from compression ignition engines and Spark-ignition engines equipment, including motor vehicles. The standards and the timeline for implementation are set by the Central Pollution Control Board under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change.

The California Smog Check Program requires vehicles that were manufactured in 1976 or later to participate in the biennial smog check program in participating counties. The program's stated aim is to reduce air pollution from vehicles by ensuring that cars with excessive emissions are repaired in accordance with federal and state guidelines. With some exceptions, gasoline-powered vehicles, hybrid vehicles, and alternative-fuel vehicles that are eight model-years old or newer are not required to participate; instead, these vehicles pay a smog abatement fee for the first 8 years in place of being required to pass a smog check. The eight-year exception does not apply to nonresident vehicles being registered in California for the first time, diesel vehicles 1998 model or newer and weighing 14,000 lbs or less, or specially constructed vehicles 1976 and newer. The program is a joint effort between the California Air Resources Board, the California Bureau of Automotive Repair, and the California Department of Motor Vehicles.

The California Statewide Truck and Bus Rule was initially adopted in December 2008 by the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and requires all heavy-duty diesel trucks and buses that operate in California to retrofit or replace engines in order to reduce diesel emissions. All privately and federally owned diesel-fueled trucks and buses, and privately and publicly owned school buses with a gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) greater than 14,000 pounds, are covered by the regulation.

Mobile source air pollution includes any air pollution emitted by motor vehicles, airplanes, locomotives, and other engines and equipment that can be moved from one location to another. Many of these pollutants contribute to environmental degradation and have negative effects on human health. To prevent unnecessary damage to human health and the environment, environmental regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have established policies to minimize air pollution from mobile sources. Similar agencies exist at the state level. Due to the large number of mobile sources of air pollution, and their ability to move from one location to another, mobile sources are regulated differently from stationary sources, such as power plants. Instead of monitoring individual emitters, such as an individual vehicle, mobile sources are often regulated more broadly through design and fuel standards. Examples of this include corporate average fuel economy standards and laws that ban leaded gasoline in the United States. The increase in the number of motor vehicles driven in the U.S. has made efforts to limit mobile source pollution challenging. As a result, there have been a number of different regulatory instruments implemented to reach the desired emissions goals.

The Worldwide harmonized Light vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP) is a global driving cycle standard for determining the levels of pollutants, CO2 emission standards and fuel consumption of conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) and hybrid automobiles, as well as the all-electric range of plug-in electric vehicles.

The Volkswagen emissions scandal, sometimes known as Dieselgate or Emissionsgate, began in September 2015, when the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a notice of violation of the Clean Air Act to German automaker Volkswagen Group. The agency had found that Volkswagen had intentionally programmed turbocharged direct injection (TDI) diesel engines to activate their emissions controls only during laboratory emissions testing, which caused the vehicles' NOx output to meet US standards during regulatory testing. However, the vehicles emitted up to 40 times more NOx in real-world driving. Volkswagen deployed this software in about 11 million cars worldwide, including 500,000 in the United States, in model years 2009 through 2015.

A defeat device is any motor vehicle hardware, software, or design that interferes with or disables emissions controls under real-world driving conditions, even if the vehicle passes formal emissions testing. The term appears in the US Clean Air Act and European Union regulations, to describe anything that prevents an emissions control system from working, and applies as well to power plants or other air pollution sources, as to automobiles.

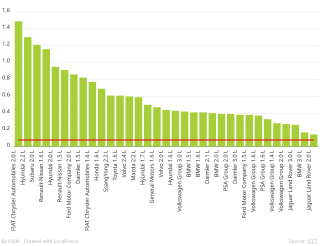

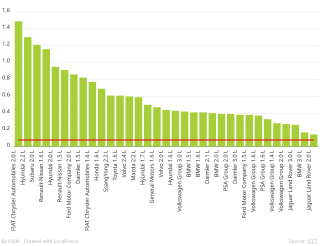

From 2014 onwards, software which manipulated air pollution tests was discovered in vehicles from some car makers; the software recognized when the standardized emissions test was being done, and adjusted the engine to emit less during the test. The cars emitted much higher levels of pollution under real-world driving conditions. Some cars' emissions were higher even though there was no manipulated software.