Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating the body's adaptive immunity, they help prevent sickness from an infectious disease. When a sufficiently large percentage of a population has been vaccinated, herd immunity results. Herd immunity protects those who may be immunocompromised and cannot get a vaccine because even a weakened version would harm them. The effectiveness of vaccination has been widely studied and verified. Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases; widespread immunity due to vaccination is largely responsible for the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the elimination of diseases such as polio and tetanus from much of the world. However, some diseases, such as measles outbreaks in America, have seen rising cases due to relatively low vaccination rates in the 2010s – attributed, in part, to vaccine hesitancy. According to the World Health Organization, vaccination prevents 3.5–5 million deaths per year.

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins. The agent stimulates the body's immune system to recognize the agent as a threat, destroy it, and recognize further and destroy any of the microorganisms associated with that agent that it may encounter in the future.

Mercury poisoning is a type of metal poisoning due to exposure to mercury. Symptoms depend upon the type, dose, method, and duration of exposure. They may include muscle weakness, poor coordination, numbness in the hands and feet, skin rashes, anxiety, memory problems, trouble speaking, trouble hearing, or trouble seeing. High-level exposure to methylmercury is known as Minamata disease. Methylmercury exposure in children may result in acrodynia in which the skin becomes pink and peels. Long-term complications may include kidney problems and decreased intelligence. The effects of long-term low-dose exposure to methylmercury are unclear.

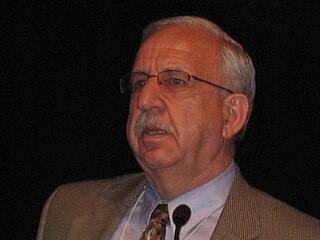

Bernard Rimland was an American research psychologist, writer, lecturer, and influential person in the field of developmental disorders. Rimland's first book, Infantile Autism, sparked by the birth of a son who had autism, was instrumental in changing attitudes toward the disorder. Rimland founded and directed two advocacy groups: the Autism Society of America (ASA) and the Autism Research Institute. He promoted several since disproven theories about the causes and treatment of autism, including vaccine denial, facilitated communication, chelation therapy, and false claims of a link between secretin and autism. He also supported the ethically controversial practice of using aversives on autistic children.

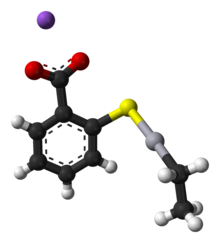

Ethylmercury (sometimes ethyl mercury) is a cation composed of an organic CH3CH2— species (an ethyl group) bound to a mercury(II) centre, making it a type of organometallic cation, and giving it a chemical formula C2H5Hg+. The main source of ethylmercury is thimerosal.

The 2000 Simpsonwood CDC conference was a two-day meeting convened in June 2000 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), held at the Simpsonwood Methodist retreat and conference center in Norcross, Georgia. The key event at the conference was the presentation of data from the Vaccine Safety Datalink examining the possibility of a link between the mercury compound thimerosol in vaccines and neurological problems in children who had received those vaccines.

Richard Carlton Deth is an American neuropharmacologist, a former professor of pharmacology at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, and is on the scientific advisory board of the National Autism Association. Deth has published scientific studies on the role of D4 dopamine receptors in psychiatric disorders, as well as the book, Molecular Origins of Human Attention: The Dopamine-Folate Connection. He has also become a prominent voice in the controversies in autism and thiomersal and vaccines, due to his hypothesis that certain children are more at risk than others because they lack the normal ability to excrete neurotoxic metals.

The Vaccine Safety Datalink Project (VSD) was established in 1990 by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to study the adverse effects of vaccines.

Thiomersal is a mercury compound which is used as a preservative in some vaccines. Anti-vaccination activists promoting the incorrect claim that vaccination causes autism have asserted that the mercury in thiomersal is the cause. There is no scientific evidence to support this claim. The idea that thiomersal in vaccines might have detrimental effects originated with anti-vaccination activists and was sustained by them and especially through the action of plaintiffs' lawyers.

A vaccine adverse event (VAE), sometimes referred to as a vaccine injury, is an adverse event believed to have been caused by vaccination. The World Health Organization (WHO) knows VAEs as Adverse Events Following Immunization (AEFI).

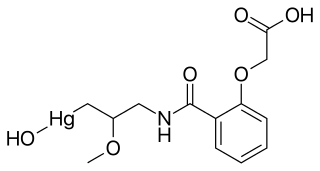

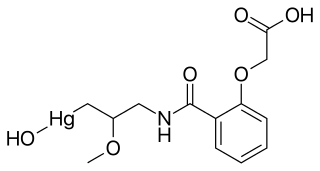

Mersalyl (Mersal) is an organomercury compound and mercurial diuretic. It is only rarely used as a drug, having been superseded by thiazides and loop diuretics that are less toxic because they do not contain mercury. It features a Hg(II) centre. Mersalyl was originally adapted from calomel (Hg2Cl2), a diuretic discovered by Paracelsus.

Organomercury chemistry refers to the study of organometallic compounds that contain mercury. Typically the Hg–C bond is stable toward air and moisture but sensitive to light. Important organomercury compounds are the methylmercury(II) cation, CH3Hg+; ethylmercury(II) cation, C2H5Hg+; dimethylmercury, (CH3)2Hg, diethylmercury and merbromin ("Mercurochrome"). Thiomersal is used as a preservative for vaccines and intravenous drugs.

The Office of Special Masters of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, popularly known as "vaccine court", administers a no-fault system for litigating vaccine injury claims. These claims against vaccine manufacturers cannot normally be filed in state or federal civil courts, but instead must be heard in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, sitting without a jury.

The 2009 swine flu pandemic vaccines were influenza vaccines developed to protect against the pandemic H1N1/09 virus. These vaccines either contained inactivated (killed) influenza virus, or weakened live virus that could not cause influenza. The killed virus was injected, while the live virus was given as a nasal spray. Both these types of vaccine were produced by growing the virus in chicken eggs. Around three billion doses were produced, with delivery in November 2009.

Nitromersol (metaphen) is a mercury-containing organic compound that is primarily used as an antiseptic and disinfectant. It is a brown-yellow solid that has no odor or taste, does not irritate the skin or mucous membranes, and has no impact on rubber or metallic instruments, including surgical and dental tools.

Michelle Cedillo v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, also known as Cedillo, was a court case involving the family of Michelle Cedillo, an autistic girl whose parents sued the United States government because they believed that her autism was caused by her receipt of both the measles-mumps-and-rubella vaccine and thimerosal-containing vaccines. The case was a part of the Omnibus Autism Proceeding, where petitioners were required to present three test cases for each proposed mechanism by which vaccines had, according to them, caused their children's autism; Cedillo was the first such case for the MMR-and-thimerosal hypothesis.

Frank DeStefano FACPM is a medical epidemiologist and researcher at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where he is director of the Immunization Safety Office.

Michael E. Pichichero is an American physician who is the Director of the Rochester General Hospital Research Institute, a Research Professor at Rochester Institute of Technology and a clinical professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Rochester Medical Center. He is the author of a number of scientific studies regarding the safety of thimerosal as a preservative in vaccines.

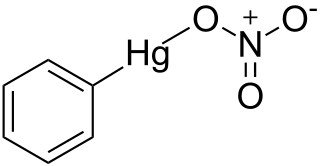

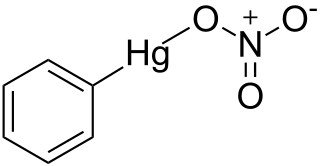

Phenylmercuric nitrate is an organomercury compound with powerful antiseptic and antifungal effects. It was once commonly used as a topical solution for disinfecting wounds, but as with all organomercury compounds it is highly toxic, especially to the kidneys, and is no longer used in this application. However it is still used in low concentrations as a preservative in eye drops for ophthalmic use, making it one of the few organomercury derivatives remaining in current medical use.

Extensive investigation into vaccines and autism has shown that there is no relationship between the two, causal or otherwise, and that vaccine ingredients do not cause autism. Vaccinologist Peter Hotez researched the growth of the false claim and concluded that its spread originated with Andrew Wakefield's fraudulent 1998 paper, with no prior paper supporting a link.