Coronaviruses are a group of related RNA viruses that cause diseases in mammals and birds. In humans and birds, they cause respiratory tract infections that can range from mild to lethal. Mild illnesses in humans include some cases of the common cold, while more lethal varieties can cause SARS, MERS and COVID-19. In cows and pigs they cause diarrhea, while in mice they cause hepatitis and encephalomyelitis.

Severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome–related coronavirus is a species of virus consisting of many known strains. Two strains of the virus have caused outbreaks of severe respiratory diseases in humans: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1, the cause of the 2002–2004 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of the pandemic of COVID-19. There are hundreds of other strains of SARSr-CoV, which are only known to infect non-human mammal species: bats are a major reservoir of many strains of SARSr-CoV; several strains have been identified in Himalayan palm civets, which were likely ancestors of SARS-CoV-1.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is an enzyme that can be found either attached to the membrane of cells (mACE2) in the intestines, kidney, testis, gallbladder, and heart or in a soluble form (sACE2). Both membrane bound and soluble ACE2 are integral parts of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) that exists to keep the body's blood pressure in check. mACE2 is cleaved by the enzyme ADAM17 in a process regulated by substrate presentation. ADAM17 cleavage releases the extracellular domain creating soluble ACE2 (sACE2). ACE2 enzyme activity opposes the classical arm of the RAAS by lowering blood pressure through catalyzing the hydrolysis of angiotensin II into angiotensin (1–7). Angiotensin (1-7) in turns binds to MasR receptors creating localized vasodilation and hence decreasing blood pressure. This decrease in blood pressure makes the entire process a promising drug target for treating cardiovascular diseases.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1), previously known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), is a strain of coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the respiratory illness responsible for the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that infects the epithelial cells within the lungs. The virus enters the host cell by binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. It infects humans, bats, and palm civets. The SARS-CoV-1 outbreak was largely brought under control by simple public health measures. Testing people with symptoms, isolating and quarantining suspected cases, and restricting travel all had an effect. SARS-CoV-1 was most transmissible when patients were sick, so its spread could be effectively suppressed by isolating patients with symptoms.

Human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63) is a species of coronavirus, specifically a Setracovirus from among the Alphacoronavirus genus. It was identified in late 2004 in patients in the Netherlands by Lia van der Hoek and Krzysztof Pyrc using a novel virus discovery method VIDISCA. Later on the discovery was confirmed by the researchers from the Rotterdam, the Netherlands The virus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to ACE2. Infection with the virus has been confirmed worldwide, and has an association with many common symptoms and diseases. Associated diseases include mild to moderate upper respiratory tract infections, severe lower respiratory tract infection, croup and bronchiolitis.

Furin is a protease, a proteolytic enzyme activated by substrate presentation that in humans and other animals is encoded by the FURIN gene. Some proteins are inactive when they are first synthesized, and must have sections removed in order to become active. Furin cleaves these sections and activates the proteins. It was named furin because it was in the upstream region of an oncogene known as FES. The gene was known as FUR and therefore the protein was named furin. Furin is also known as PACE. A member of family S8, furin is a subtilisin-like peptidase.

Murine coronavirus (M-CoV) is a virus in the genus Betacoronavirus that infects mice. Belonging to the subgenus Embecovirus, murine coronavirus strains are enterotropic or polytropic. Enterotropic strains include mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) strains D, Y, RI, and DVIM, whereas polytropic strains, such as JHM and A59, primarily cause hepatitis, enteritis, and encephalitis. Murine coronavirus is an important pathogen in the laboratory mouse and the laboratory rat. It is the most studied coronavirus in animals other than humans, and has been used as an animal disease model for many virological and clinical studies.

Transmembrane protease, serine 2 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the TMPRSS2 gene. It belongs to the TMPRSS family of proteins, whose members are transmembrane proteins which have a serine protease activity. The TMPRSS2 protein is found in high concentration in the cell membranes of epithelial cells of the lung and of the prostate, but also in the heart, liver and gastrointestinal tract.

Novel coronavirus (nCoV) is a provisional name given to coronaviruses of medical significance before a permanent name is decided upon. Although coronaviruses are endemic in humans and infections normally mild, such as the common cold, cross-species transmission has produced some unusually virulent strains which can cause viral pneumonia and in serious cases even acute respiratory distress syndrome and death.

The 3C-like protease (3CLpro) or main protease (Mpro), formally known as C30 endopeptidase or 3-chymotrypsin-like protease, is the main protease found in coronaviruses. It cleaves the coronavirus polyprotein at eleven conserved sites. It is a cysteine protease and a member of the PA clan of proteases. It has a cysteine-histidine catalytic dyad at its active site and cleaves a Gln–(Ser/Ala/Gly) peptide bond.

Betacoronavirus is one of four genera of coronaviruses. Member viruses are enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses that infect mammals, including humans. The natural reservoir for betacoronaviruses are bats and rodents. Rodents are the reservoir for the subgenus Embecovirus, while bats are the reservoir for the other subgenera.

Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) is a species of coronavirus which infects humans and bats. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the APN receptor. Along with Human coronavirus OC43, it is one of the viruses responsible for the common cold. HCoV-229E is a member of the genus Alphacoronavirus and subgenus Duvinacovirus.

Positive-strand RNA viruses are a group of related viruses that have positive-sense, single-stranded genomes made of ribonucleic acid. The positive-sense genome can act as messenger RNA (mRNA) and can be directly translated into viral proteins by the host cell's ribosomes. Positive-strand RNA viruses encode an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) which is used during replication of the genome to synthesize a negative-sense antigenome that is then used as a template to create a new positive-sense viral genome.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the provisional name 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), and has also been called human coronavirus 2019. First identified in the city of Wuhan, Hubei, China, the World Health Organization designated the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern from January 30, 2020, to May 5, 2023. SARS‑CoV‑2 is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus that is contagious in humans.

SHC014-CoV is a SARS-like coronavirus (SL-COV) which infects horseshoe bats. It was discovered in Kunming in Yunnan Province, China. It was discovered along with SL-CoV Rs3367, which was the first bat SARS-like coronavirus shown to directly infect a human cell line. The line of Rs3367 that infected human cells was named Bat SARS-like coronavirus WIV1.

Bat coronavirus RaTG13 is a SARS-like betacoronavirus identified in the droppings of the horseshoe bat Rhinolophus affinis. It was discovered in 2013 in bat droppings from a mining cave near the town of Tongguan in Mojiang county in Yunnan, China. In February 2020, it was identified as the closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, sharing 96.1% nucleotide identity. However, in 2022, scientists found three closer matches in bats found 530 km south, in Feuang, Laos, designated as BANAL-52, BANAL-103 and BANAL-236.

The COVID-19 lab leak theory, or lab leak hypothesis, is the idea that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic, came from a laboratory. This claim is highly controversial; most scientists believe the virus spilled into human populations through natural zoonosis, similar to the SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV outbreaks, and consistent with other pandemics in human history. Available evidence suggests that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was originally harbored by bats, and spread to humans from infected wild animals, functioning as an intermediate host, at the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan, Hubei, China, in December 2019. Several candidate animal species have been identified as potential intermediate hosts. There is no evidence SARS-CoV-2 existed in any laboratory prior to the pandemic, or that any suspicious biosecurity incidents happened in any laboratory.

Civet SARS-CoV is a coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), which infected humans and caused SARS events from 2002 to 2003. It infected the masked palm civet. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) is highly similar, with a genome sequence similarity of about 99.8%. Because several patients infected at the early stage of the epidemic had contact with fruit-eating Japanese raccoon dog in the market, tanuki may be a direct source of human SARS coronavirus. At the end of 2003, four more people in Guangzhou, China, were infected with the disease. Sequence analysis found that the similarity with the tanuki virus reached 99.9%, and the SARS coronavirus was also caused by cases of tanuki transmission.

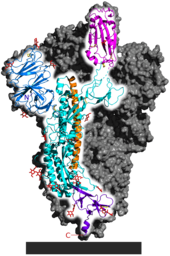

Spike (S) glycoprotein is the largest of the four major structural proteins found in coronaviruses. The spike protein assembles into trimers that form large structures, called spikes or peplomers, that project from the surface of the virion. The distinctive appearance of these spikes when visualized using negative stain transmission electron microscopy, "recalling the solar corona", gives the virus family its main name.

A universal coronavirus vaccine, also known as a pan-coronavirus vaccine, is a theoretical coronavirus vaccine that would be effective against all coronavirus strains. A universal vaccine would provide protection against coronavirus strains that have caused disease in humans, such as SARS-CoV-2, while also providing protection against future coronavirus strains. Such a vaccine has been proposed to prevent or mitigate future coronavirus epidemics and pandemics.