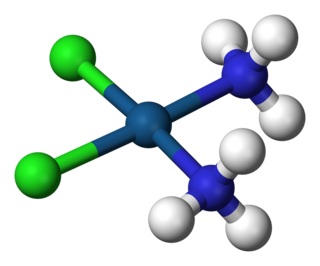

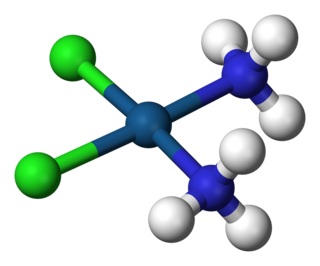

A coordination complex is a chemical compound consisting of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the coordination centre, and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn known as ligands or complexing agents. Many metal-containing compounds, especially those that include transition metals, are coordination complexes.

In chemistry, a transition metal is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table, though the elements of group 12 are sometimes excluded. The lanthanide and actinide elements are called inner transition metals and are sometimes considered to be transition metals as well.

In theoretical chemistry, a conjugated system is a system of connected p-orbitals with delocalized electrons in a molecule, which in general lowers the overall energy of the molecule and increases stability. It is conventionally represented as having alternating single and multiple bonds. Lone pairs, radicals or carbenium ions may be part of the system, which may be cyclic, acyclic, linear or mixed. The term "conjugated" was coined in 1899 by the German chemist Johannes Thiele.

The octet rule is a chemical rule of thumb that reflects the theory that main-group elements tend to bond in such a way that each atom has eight electrons in its valence shell, giving it the same electronic configuration as a noble gas. The rule is especially applicable to carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and the halogens; although more generally the rule is applicable for the s-block and p-block of the periodic table. Other rules exist for other elements, such as the duplet rule for hydrogen and helium, and the 18-electron rule for transition metals.

In chemistry and physics, valence electrons are electrons in the outermost shell of an atom, and that can participate in the formation of a chemical bond if the outermost shell is not closed. In a single covalent bond, a shared pair forms with both atoms in the bond each contributing one valence electron.

In organometallic chemistry, the isolobal principle is a strategy used to relate the structure of organic and inorganic molecular fragments in order to predict bonding properties of organometallic compounds. Roald Hoffmann described molecular fragments as isolobal "if the number, symmetry properties, approximate energy and shape of the frontier orbitals and the number of electrons in them are similar – not identical, but similar." One can predict the bonding and reactivity of a lesser-known species from that of a better-known species if the two molecular fragments have similar frontier orbitals, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). Isolobal compounds are analogues to isoelectronic compounds that share the same number of valence electrons and structure. A graphic representation of isolobal structures, with the isolobal pairs connected through a double-headed arrow with half an orbital below, is found in Figure 1.

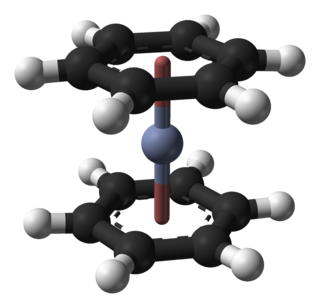

Nickelocene is the organonickel compound with the formula Ni(η5-C5H5)2. Also known as bis(cyclopentadienyl)nickel or NiCp2, this bright green paramagnetic solid is of enduring academic interest, although it does not yet have any known practical applications.

A quintuple bond in chemistry is an unusual type of chemical bond, first reported in 2005 for a dichromium compound. Single bonds, double bonds, and triple bonds are commonplace in chemistry. Quadruple bonds are rarer and are currently known only among the transition metals, especially for Cr, Mo, W, and Re, e.g. [Mo2Cl8]4− and [Re2Cl8]2−. In a quintuple bond, ten electrons participate in bonding between the two metal centers, allocated as σ2π4δ4.

In chemistry, the square planar molecular geometry describes the stereochemistry that is adopted by certain chemical compounds. As the name suggests, molecules of this geometry have their atoms positioned at the corners.

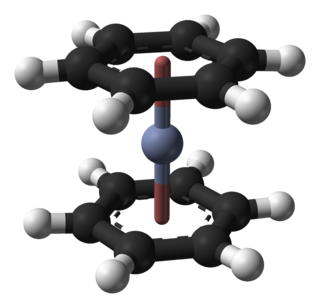

Bis(benzene)chromium is the organometallic compound with the formula Cr(η6-C6H6)2. It is sometimes called dibenzenechromium. The compound played an important role in the development of sandwich compounds in organometallic chemistry and is the prototypical complex containing two arene ligands.

An electric effect influences the structure, reactivity, or properties of a molecule but is neither a traditional bond nor a steric effect. In organic chemistry, the term stereoelectronic effect is also used to emphasize the relation between the electronic structure and the geometry (stereochemistry) of a molecule.

The d electron count or number of d electrons is a chemistry formalism used to describe the electron configuration of the valence electrons of a transition metal center in a coordination complex. The d electron count is an effective way to understand the geometry and reactivity of transition metal complexes. The formalism has been incorporated into the two major models used to describe coordination complexes; crystal field theory and ligand field theory, which is a more advanced version based on molecular orbital theory. However the d electron count of an atom in a complex is often different from the d electron count of a free atom or a free ion of the same element.

Spin states when describing transition metal coordination complexes refers to the potential spin configurations of the central metal's d electrons. For several oxidation states, metals can adopt high-spin and low-spin configurations. The ambiguity only applies to first row metals, because second- and third-row metals are invariably low-spin. These configurations can be understood through the two major models used to describe coordination complexes; crystal field theory and ligand field theory.

The Tolman electronic parameter (TEP) is a measure of the electron donating or withdrawing ability of a ligand. It is determined by measuring the frequency of the A1 C-O vibrational mode (ν(CO)) of a (pseudo)-C3v symmetric complex, [LNi(CO)3] by infrared spectroscopy, where L is the ligand of interest. [LNi(CO)3] was chosen as the model compound because such complexes are readily prepared from tetracarbonylnickel(0). The shift in ν(CO) is used to infer the electronic properties of a ligand, which can aid in understanding its behavior in other complexes. The analysis was introduced by Chadwick A. Tolman.

In inorganic chemistry, the cis effect is defined as the labilization of CO ligands that are cis to other ligands. CO is a well-known strong pi-accepting ligand in organometallic chemistry that will labilize in the cis position when adjacent to ligands due to steric and electronic effects. The system most often studied for the cis effect is an octahedral complex M(CO)

5X where X is the ligand that will labilize a CO ligand cis to it. Unlike the trans effect, which is most often observed in 4-coordinate square planar complexes, the cis effect is observed in 6-coordinate octahedral transition metal complexes. It has been determined that ligands that are weak sigma donors and non-pi acceptors seem to have the strongest cis-labilizing effects. Therefore, the cis effect has the opposite trend of the trans-effect, which effectively labilizes ligands that are trans to strong pi accepting and sigma donating ligands.

A borylene is the boron analogue of a carbene. The general structure is R-B: with R an organic moiety and B a boron atom with two unshared electrons. Borylenes are of academic interest in organoboron chemistry. A singlet ground state is predominant with boron having two vacant sp2 orbitals and one doubly occupied one. With just one additional substituent the boron is more electron deficient than the carbon atom in a carbene. For this reason stable borylenes are more uncommon than stable carbenes. Some borylenes such as boron monofluoride (BF) and boron monohydride (BH) the parent compound also known simply as borylene, have been detected in microwave spectroscopy and may exist in stars. Other borylenes exist as reactive intermediates and can only be inferred by chemical trapping.

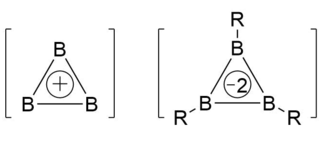

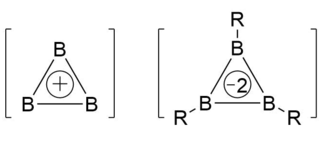

The triboracyclopropenyl fragment is a cyclic structural motif in boron chemistry, named for its geometric similarity to cyclopropene. In contrast to nonplanar borane clusters that exhibit higher coordination numbers at boron (e.g., through 3-center 2-electron bonds to bridging hydrides or cations), triboracyclopropenyl-type structures are rings of three boron atoms where substituents at each boron are also coplanar to the ring. Triboracyclopropenyl-containing compounds are extreme cases of inorganic aromaticity. They are the lightest and smallest cyclic structures known to display the bonding and magnetic properties that originate from fully delocalized electrons in orbitals of σ and π symmetry. Although three-membered rings of boron are frequently so highly strained as to be experimentally inaccessible, academic interest in their distinctive aromaticity and possible role as intermediates of borane pyrolysis motivated extensive computational studies by theoretical chemists. Beginning in the late 1980s with mass spectrometry work by Anderson et al. on all-boron clusters, experimental studies of triboracyclopropenyls were for decades exclusively limited to gas-phase investigations of the simplest rings (ions of B3). However, more recent work has stabilized the triboracyclopropenyl moiety via coordination to donor ligands or transition metals, dramatically expanding the scope of its chemistry.

Alkaline earth octacarbonyl complexes are a class of neutral compounds that have the general formula M(CO)8 where M is a heavy Group 2 element (Ca, Sr, or Ba). The metal center has a formal oxidation state of 0 and the complex has a high level of symmetry belonging to the cubic Oh point group. These complexes are isolable in a low-temperature neon matrix, but are not frequently used in applications due to their instability in air and water. The bonding within these complexes is controversial with some arguing the bonding resembles a model similar to bonding in transition metal carbonyl complexes which abide by the 18-electron rule, and others arguing the molecule more accurately contains ionic bonds between the alkaline earth metal center and the carbonyl ligands. Complexes of Be(CO)8 and Mg(CO)8 are not synthetically possible due to inaccessible (n-1)d orbitals. Beryllium has been found to form a dinuclear homoleptic carbonyl and magnesium a mononuclear heteroleptic carbonyl, both with only two carbonyl ligands instead of eight to each metal atom.

Carbones are a class of molecules containing a carbon atom in the 1D excited state with a formal oxidation state of zero where all four valence electrons exist as unbonded lone pairs. These carbon-based compounds are of the formula CL2 where L is a strongly σ-donating ligand, typically a phosphine (carbodiphosphoranes) or a N-heterocyclic carbene/NHC (carbodicarbenes), that stabilises the central carbon atom through donor-acceptor bonds. Carbones possess high-energy orbitals with both σ- and π-symmetry, making them strong Lewis bases and strong π-backdonor substituents. Carbones possess high proton affinities and are strong nucleophiles which allows them to function as ligands in a variety of main group and transition metal complexes. Carbone-coordinated elements also exhibit a variety of different reactivities and catalyse various organic and main group reactions.

While the first dinitrogen complex was discovered in 1965, reports of dinitrogen complexes of main group elements have been significantly limited relative to their transition metal complex analogues. Examples span both the s- and p- blocks, with particular breakthroughs in Groups 1, 2, 13, 14, and 15 in the periodic table. These complexes tend to involve somewhat weak interactions between N2 and the main group atoms it binds. The formation of such compounds is of interest to chemists who seek to extend transition metal reactivity into the main group elements and especially those interested in using main group-mediated N2 activation.