It has been requested that the title of this article be changed to 2017 Stockholm truck attack . Please see the relevant discussion on the discussion page. Do not move the page until the discussion has reached consensus for the change and is closed. |

| 2017 Stockholm attack | |

|---|---|

| Part of Terrorism in Sweden (Islamic terrorism in Europe (2014–present)) | |

The truck used in the attack being removed from the scene | |

| |

| Location | Drottninggatan, Stockholm |

| Coordinates | 59°19′58″N018°03′44″E / 59.33278°N 18.06222°E Coordinates: 59°19′58″N018°03′44″E / 59.33278°N 18.06222°E |

| Date | 7 April 2017 c. 14:53 Central European Summer Time (UTC+2) |

| Target | Swedish citizens, Tourists |

Attack type | Vehicle-ramming attack |

| Weapons | Hijacked Mercedes-Benz Actros [3] |

| Deaths | 5 [4] |

Non-fatal injuries | 14 serious [5] |

| Perpetrator | Rakhmat Akilov |

| Motive | Islamic terrorism Swedish government military training in Iraq |

On 7 April 2017, in central Stockholm, the capital of Sweden, a hijacked lorry was deliberately driven into crowds along Drottninggatan (Queen Street) before being crashed through a corner of an Åhléns department store. Five people were killed and 14 others were seriously injured.

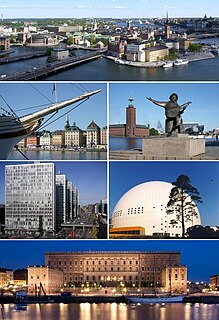

Stockholm is the capital of Sweden and the most populous urban area in the Nordic countries; 960,031 people live in the municipality, approximately 1.5 million in the urban area, and 2.3 million in the metropolitan area. The city stretches across fourteen islands where Lake Mälaren flows into the Baltic Sea. Just outside the city and along the coast is the island chain of the Stockholm archipelago. The area has been settled since the Stone Age, in the 6th millennium BC, and was founded as a city in 1252 by Swedish statesman Birger Jarl. It is also the capital of Stockholm County.

Sweden, officially the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Scandinavian Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north and Finland to the east, and is connected to Denmark in the southwest by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund, a strait at the Swedish-Danish border. At 450,295 square kilometres (173,860 sq mi), Sweden is the largest country in Northern Europe, the third-largest country in the European Union and the fifth largest country in Europe by area. Sweden has a total population of 10.2 million of which 2.4 million has a foreign background. It has a low population density of 22 inhabitants per square kilometre (57/sq mi). The highest concentration is in the southern half of the country.

A vehicle-ramming attack is an assault in which a perpetrator deliberately rams a vehicle into a building, crowd of people, or another vehicle. The earliest known use of a vehicle-ramming attack took place in 1973 in Prague, former Czechoslovakia, when Olga Hepnarová killed 8 people. According to Stratfor Global Intelligence analysts, this attack represented a new militant tactic which is less lethal but could prove more difficult to prevent than suicide bombings.

Contents

- Attack

- Casualties

- Aftermath

- Immediate response

- Reactions

- Suspect

- Legal proceedings

- Further investigation

- See also

- Notes

- References

- External links

Police considered the attack an act of terrorism. Rakhmat Akilov, a 39-year-old rejected asylum seeker born in the Soviet Union and a citizen of Uzbekistan, was apprehended the same day, suspected on probable cause of terrorist crimes through murder (a Swedish legal term). Swedish police said he has expressed sympathy with extremist organizations, among them the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), [6] and Uzbek authorities said he had allegedly joined ISIL before the attack. [7] According to the head prosecutor, Akilov had sworn his allegiance to the Islamic State in a self-recorded video the day before the attack. [8] Akilov admitted to carrying out the attack at a pre-trial hearing on 11 April.

An asylum seeker is a person who flees their home country, enters another country and applies for asylum, i.e. the right to international protection, in this other country. An asylum seeker is a type of migrant and may be a refugee, a displaced person, but not an economic migrant. Migrants are not necessarily asylum seekers. A person becomes an asylum seeker by making a formal application for the right to remain in another country and keeps that status until the application has been concluded. The applicant becomes an "asylee" if their claim is accepted and asylum is granted. The relevant immigration authorities of the country of asylum determine whether the asylum seeker will be granted protection and become an officially recognised refugee (asylee) or whether asylum will be refused and asylum seeker becomes an illegal immigrant who has to leave the country and may even be deported. The asylum seeker may be recognised as a refugee and given refugee status if the person's circumstances fall into the definition of "refugee" according to the 1951 Refugee Convention or other refugee laws, such as the European Convention on Human Rights – if asylum is claimed within the European Union. However signatories to the refugee convention create their own policies for assessing the protection status of asylum seekers, and the proportion of asylum applicants who are rejected varies from country to country and year to year.

The terms asylum seeker and refugee are often confused: an asylum-seeker is someone who says he or she is a refugee, but whose claim has not yet been definitively evaluated. On average, about 1 million people seek asylum on an individual basis every year.

The Soviet Union, officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), was a socialist state in Eurasia that existed from 30 December 1922 to 26 December 1991. Nominally a union of multiple national Soviet republics, its government and economy were highly centralized. The country was a one-party state, governed by the Communist Party with Moscow as its capital in its largest republic, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. Other major urban centres were Leningrad, Kiev, Minsk, Alma-Ata, and Novosibirsk.

Uzbekistan, officially also the Republic of Uzbekistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. The sovereign state is a secular, unitary constitutional republic, comprising 12 provinces, one autonomous republic, and a capital city. Uzbekistan is bordered by five landlocked countries: Kazakhstan to the north; Kyrgyzstan to the northeast; Tajikistan to the southeast; Afghanistan to the south; and Turkmenistan to the southwest. Along with Liechtenstein, it is one of the world's only two doubly landlocked countries.

Rakhmat Akilov was sentenced to life in prison and lifetime expulsion from Sweden on 7 June 2018. [9]

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted persons are to remain in prison either for the rest of their natural life or until paroled. Crimes for which, in some countries, a person could receive this sentence include murder, attempted murder, conspiracy to commit murder, blasphemy, apostasy, terrorism, severe child abuse, rape, child rape, espionage, treason, high treason, drug dealing, drug trafficking, drug possession, human trafficking, severe cases of fraud, severe cases of financial crimes, aggravated criminal damage in English law, and aggravated cases of arson, kidnapping, burglary, or robbery which result in death or grievous bodily harm, piracy, aircraft hijacking, and in certain cases genocide, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, certain war crimes or any three felonies in case of three strikes law. Life imprisonment can also be imposed, in certain countries, for traffic offenses causing death. The life sentence does not exist in all countries, and Portugal was the first to abolish life imprisonment, in 1884.