Related Research Articles

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda, was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture first fought and allied with Spanish forces against Saint-Domingue Royalists, then joined with Republican France, becoming Governor-General-for-life of Saint-Domingue, and lastly fought against Bonaparte's republican troops. As a revolutionary leader, Louverture displayed military and political acumen that helped transform the fledgling slave rebellion into a revolutionary movement. Along with Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Louverture is now known as one of the "Fathers of Haiti".

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not enslaved. However, the term also applied to people born free who were primarily of black African descent with little mixture. They were a distinct group of free people of color in the French colonies, including Louisiana and in settlements on Caribbean islands, such as Saint-Domingue (Haiti), St. Lucia, Dominica, Guadeloupe, and Martinique. In these territories and major cities, particularly New Orleans, and those cities held by the Spanish, a substantial third class of primarily mixed-race, free people developed. These colonial societies classified mixed-race people in a variety of ways, generally related to visible features and to the proportion of African ancestry. Racial classifications were numerous in Latin America.

Obeah, also spelled Obiya or Obia, is a broad term for African diasporic religious, spell-casting, and healing traditions found primarily in the former British colonies of the Caribbean. These practices derive much from West African traditions but also incorporate elements of European and South Asian origin. Many of those who practice these traditions avoid the term Obeah due to the word's pejorative connotations in many Caribbean societies.

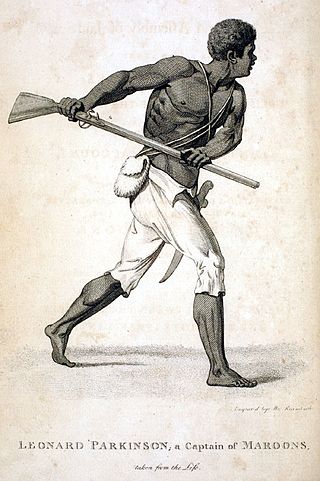

Maroons are descendants of Africans in the Americas and Islands of the Indian Ocean who escaped from slavery, through flight or manumission, and formed their own settlements. They often mixed with Indigenous peoples, eventually evolving into separate creole cultures such as the Garifuna and the Mascogos.

François Mackandal was a Haitian Maroon leader in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. He is sometimes described as a Haitian vodou priest, or houngan. For joining the Maroons to kill slave owners in Saint-Domingue, he was captured and burned alive by French colonial authorities. His actions were seen as a precursor to the Haitian Revolution.

Queen Nanny, Granny Nanny, or Nanny of the Maroons ONH, was an early-18th-century freedom fighter and leader of the Jamaican Maroons. She led a community of formerly-enslaved escapees, the majority of them West African in descent, called the Windward Maroons, along with their children and families. At the beginning of the 18th century, under the leadership of Nanny, the Windward Maroons fought a guerrilla war lasting many years against British authorities in the Colony of Jamaica, in what became known as the First Maroon War.

Afro-Caribbean or African Caribbeanpeople are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Africa. The majority of the modern Afro-Caribbean people descend from the Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the trans-Atlantic slave trade between the 15th and 19th centuries to work primarily on various sugar plantations and in domestic households. Other names for the ethnic group include Black Caribbean, Afro- or Black West Indian, or Afro- or Black Antillean. The term West Indian Creole has also been used to refer to Afro-Caribbean people, as well as other ethnic and racial groups in the region, though there remains debate about its use to refer to Afro-Caribbean people specifically. The term Afro-Caribbean was not coined by Caribbean people themselves but was first used by European Americans in the late 1960s.

The First Maroon War was a conflict between the Jamaican Maroons and the colonial British authorities that started around 1728 and continued until the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740. It was led by Indigenous Jamaican born to the land who helped liberated Africans to set up communities in the mountains who were coming off of slave ships. The name "Maroon" was given to these Africans, and for many years they fought the British colonial Government of Jamaica for their freedom. The maroons were skilled in guerrilla warfare. It was followed about half a century later by the Second Maroon War.

The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution is a 1938 book by Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James, and is a history of the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804.

Jamaican Maroons descend from Africans who freed themselves from slavery in the Colony of Jamaica and established communities of free black people in the island's mountainous interior, primarily in the eastern parishes. Africans who were enslaved during Spanish rule over Jamaica (1493–1655) may have been the first to develop such refugee communities.

Caribbean Americans or West Indian Americans are Americans who trace their ancestry to the Caribbean. Caribbean Americans are a multi-ethnic and multi-racial group that trace their ancestry further in time to Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. As of 2016, about 13 million — about 4% of the total U.S. population — have Caribbean ancestry.

Amy Ashwood Garvey was a Jamaican Pan-Africanist activist. She was a director of the Black Star Line Steamship Corporation, and along with her former husband Marcus Garvey she founded the Negro World newspaper.

The African diaspora in the Americas refers to the people born in the Americas with partial, predominant, or complete sub-Saharan African ancestry. Many are descendants of persons enslaved in Africa and transferred to the Americas by Europeans, then forced to work mostly in European-owned mines and plantations, between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. Significant groups have been established in the United States, in Canada, in the Caribbean (Afro-Caribbean), and in Latin America.

Black nationalism is a nationalist movement which seeks representation for Black people as a distinct national identity, especially in racialized, colonial and postcolonial societies. Its earliest proponents saw it as a way to advocate for democratic representation in culturally plural societies or to establish self-governing independent nation-states for Black people. Modern Black nationalism often aims for the social, political, and economic empowerment of Black communities within white majority societies, either as an alternative to assimilation or as a way to ensure greater representation and equality within predominantly Eurocentric cultures.

Cécile Fatiman was a Haitian Vodou priestess and revolutionary. Born to an enslaved African woman and a Corsican prince, she lived her early life in slavery, before being drawn to Enlightenment ideals of "liberté, égalité, fraternité" and Haitian Vodou, which shaped her desire to end the institution of slavery in Haiti. Together with Dutty Boukman, she led a Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman and incited enslaved people to rise up against slavery, in an event that marked the beginning of the Haitian Revolution. She later married fellow revolutionary leader Jean-Louis Pierrot, with whom she had a daughter. She was reported to have lived a long life, dying at the age of 112.

Slavery in Cuba was a portion of the larger Atlantic slave trade that primarily supported Spanish plantation owners engaged in the sugarcane trade. It was practiced on the island of Cuba from the 16th century until it was abolished by Spanish royal decree on October 7, 1886.

During the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), Haitian women of all social positions participated in the revolt that successfully ousted French colonial power from the island. The 1791 revolt of enslaved individuals in Saint-Domingue was the most extensive and prosperous slave rebellion in recent times. In spite of their various important roles in the Haitian Revolution, women revolutionaries have rarely been included within historical and literary narratives of the slave revolts. However, in recent years extensive academic research has been dedicated to their part in the revolution.

The city of Baltimore, Maryland includes a large and growing Caribbean-American population. The Caribbean-American community is centered in West Baltimore. The largest non-Hispanic Caribbean populations in Baltimore are Jamaicans, Trinidadians and Tobagonians, and Haitians. Baltimore also has significant Hispanic populations from the Spanish West Indies, particularly Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and Cubans. Northwest Baltimore is the center of the West Indian population of Baltimore, while Caribbean Hispanics in the city tend to live among other Latinos in neighborhoods such as Greektown, Upper Fell's Point, and Highlandtown. Jamaicans and Trinidadians are the first and second largest West Indian groups in the city, respectively. The neighborhoods of Park Heights and Pimlico in northwest Baltimore are home to large West Indian populations, particularly Jamaican-Americans.

The French revolutionary government granted citizenship and freedom to free people of color in May 1791, but white planters in Saint-Domingue refused to comply with this decision. This was the catalyst for the 1791 slave rebellion, a key event for the Haitian Revolution with which the new citizens demanded their granted rights.

References

- ↑ David M. Traboulay (1994). Columbus and Las Casas: the conquest and Christianization of America, 1492–1566. University Press of America. p. 44. ISBN 9780819196422 . Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ↑ Some historical account of Guinea: With an inquiry into the rise and progress of the slave trade , p. 48, at Google Books

- ↑ Stephen D. Behrendt, David Richardson, and David Eltis, W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research, Harvard University. Based on "records for 27,233 voyages that set out to obtain slaves for the Americas". Behrendt, Stephen (1999). "Transatlantic Slave Trade". Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience . New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 0-465-00071-1.

- ↑ Jerome S. Handler and John T. Pohlmann, "Slave Manumissions and Freedmen in Seventeenth-Century Barbados", in The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 41, No. 3, July 1984, pp. 390-408..

- ↑ "Government of Jamaica, national heroes listing". Archived from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ Patterson, Orlando (1970), "Slavery and Slave Revolts: A Sociohistorical Analysis of the First Maroon War, 1665-1740", in Richard Price, Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas, Anchor Books, 1973, ISBN 0-385-06508-6

- ↑ C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, Vintage Books, 1963, Penguin Books, 2001. ISBN 0-14-029981-5

- ↑ Philip Sherlock, 1998. Story of the Jamaican People, Central.

- ↑ Tony Martin, Race First: The Ideological and Organizational Struggle of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1976.

- ↑ Malela, Buata B., Aimé Césaire. Le fil et la trame: critique et figuration de la colonialité du pouvoir. Paris: Anibwe, 2009.

- ↑ Nigel C. Gibson, Fanon: The Postcolonial Imagination (2003: Oxford, Polity Press)

- ↑ Chen, Kuan-Hsing. "The Formation of a Diasporic Intellectual: An interview with Stuart Hall," collected in David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen (eds), Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. New York: Routledge, 1996.

- ↑ "Poverty, income inequality on the rise in Jamaica - report". jamaica-gleaner.com. October 9, 2011.

- ↑ Bogues, Anthony (2003). Black Heretics, Black Prophets: Radical Political Intellectuals. New York: Routledge. pp. 25–46.