The economy of Angola remains heavily influenced by the effects of four decades of conflict in the last part of the 20th century, the war for independence from Portugal (1961–75) and the subsequent civil war (1975–2002). Poverty since 2002 is reduced over 50% and a third of the population relies on subsistence agriculture. Since 2002, when the 27-year civil war ended, government policy prioritized the repair and improvement of infrastructure and strengthening of political and social institutions. During the first decade of the 21st century, Angola's economy was one of the fastest-growing in the world, with reported annual average GDP growth of 11.1 percent from 2001 to 2010. High international oil prices and rising oil production contributed to strong economic growth, although with high inequality, at that time. 2022 trade surplus was $30 billion, compared to $48 billion in 2012.

Agriculture is a major sector of the Nigerian economy, accounting for up to 35% of total employment in 2020. According to the FAO, agriculture remains the foundation of the Nigerian economy, providing livelihood for most Nigerians and generating millions of jobs. Along with crude oil, Nigeria relies on the agricultural products it exports to generate most of its national revenue. The agricultural sector in Nigeria comprises four sub-sectors: crop production, livestock, forestry, and fishing.

The agriculture of Brazil is historically one of the principal bases of Brazil's economy. As of 2024 the country is the second biggest grain exporter in the world, with 19% of the international market share, and the fourth overall grain producer. Brazil is also the world's largest exporter of many popular agriculture commodities like coffee, soybeans, organic honey, beef, poultry, cane sugar, açai berry, orange juice, yerba mate, cellulose, tobacco, and the second biggest exporter of maize, pork, cotton, and ethanol. The country also has a significant presence as producer and exporter of rice, wheat, eggs, refined sugar, cocoa, beans, nuts, cassava, sisal fiber, and diverse fruits and vegetables.

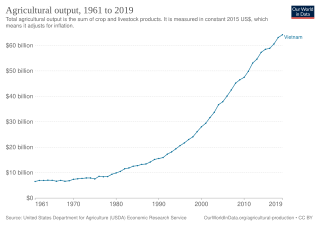

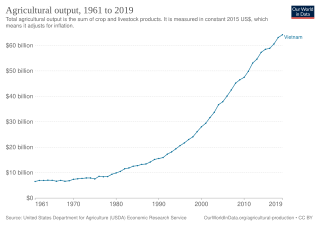

Agriculture's share of GDP has declined in recent years, falling from 42% in 1989, to 26% in 1999. In 2023, agriculture and forestry accounted for about 12% of Vietnam's gross domestic product (GDP). However, agricultural employment was much higher than agriculture's share of GDP; in 2005, approximately 60 percent of the employed labor force was engaged in agriculture, forestry, and fishing. Agricultural products accounted for 30 percent of exports in 2005. The relaxation of the state monopoly on rice exports transformed the country into the world's second or third largest rice exporter. Other cash crops are coffee, cotton, peanuts, rubber, sugarcane, and tea.

The People's Republic of China (PRC) primarily produces rice, wheat, potatoes, tomatoes, sorghum, peanuts, tea, millet, barley, cotton, oilseed, corn and soybeans.

Agriculture in Colombia refers to all agricultural activities, essential to food, feed, and fiber production, including all techniques for raising and processing livestock within the Republic of Colombia. Plant cultivation and livestock production have continuously abandoned subsistence agricultural practices in favour of technological farming resulting in cash crops which contribute to the economy of Colombia. The Colombian agricultural production has significant gaps in domestic and/or international human and animal sustenance needs.

Agriculture in Ghana consists of a variety of agricultural products and is an established economic sector, providing employment on a formal and informal basis. It is represented by the Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Ghana produces a variety of crops in various climatic zones which range from dry savanna to wet forest which run in east–west bands across Ghana. Agricultural crops, including yams, grains, cocoa, oil palms, kola nuts, and timber, form the base of agriculture in Ghana's economy. In 2013 agriculture employed 53.6% of the total labor force in Ghana.

Agriculture in Ethiopia is the foundation of the country's economy, accounting for half of gross domestic product (GDP), 0

Agriculture employs the majority of Madagascar's population. Mainly involving smallholders, agriculture has seen different levels of state organisation, shifting from state control to a liberalized sector.

Uganda's favorable soil conditions and climate have contributed to the country's agricultural success. Most areas of Uganda have usually received plenty of rain. In some years, small areas of the southeast and southwest have averaged more than 150 millimeters per month. In the north, there is often a short dry season in December and January. Temperatures vary only a few degrees above or below 20 °C but are moderated by differences in altitude.

Agriculture in Algeria composes 25% of Algeria's economy and 12% of its GDP in 2010. Prior to Algeria’ colonization in 1830, nonindustrial agriculture provided sustenance for its population of approximately 2-3 million. Domestic agriculture production included wheat, barley, citrus fruits, dates, nuts, and olives. After 1830, colonizers introduced 2200 individual farms operated by private sectors. Colonial farmers continued to produce a variety of fruits, nuts, wheat, vegetables. Algeria became a large producer of wine during the late 19th century due to a crop epidemic that spread across France. Algeria's agriculture evolved after independence was achieved in 1962. The industry experienced multiple policy changes modernize and decry on food imports. Today, Algeria's agriculture industry continues to expand modern irrigation and size of cultivable land.

Benin is predominantly a rural society, and agriculture in Benin supports more than 70% of the population. Agriculture contributes around 35% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) and 80% of export income. While the Government of Benin (GOB) aims to diversify its agricultural production, Benin remains underdeveloped, and its economy is underpinned by subsistence agriculture. Approximately 93% of total agricultural production goes into food production. The proportion of the population living in poverty is about 35.2%, with more rural households in poverty (38.4%) than urban households (29.8%). 36% of households depend solely upon agricultural (crop) production for income, and another 30% depend on crop production, livestock, or fishing for income.

Agriculture in Cameroon is an industry that has plenty of potential.

Agriculture in Sudan plays an important role in that country's economy. Agriculture and livestock raising are the main sources of livelihood for most of the Sudanese population. It was estimated that, as of 2011, 80 percent of the labor force were employed in that sector, including 84 percent of the women and 64 percent of the men.

The role of agriculture in the Bolivian economy in the late 1980s expanded as the collapse of the tin industry forced the country to diversify its productive and export base. Agricultural production as a share of GDP was approximately 23 percent in 1987, compared with 30 percent in 1960 and a low of just under 17 percent in 1979. The recession of the 1980s, along with unfavorable weather conditions, particularly droughts and floods, hampered output. Agriculture employed about 46 percent of the country's labor force in 1987. Most production, with the exception of coca, focused on the domestic market and self-sufficiency in food. Agricultural exports accounted for only about 15 percent of total exports in the late 1980s, depending on weather conditions and commodity prices for agricultural goods, hydrocarbons, and minerals.

Throughout its history, agriculture in Paraguay has been the mainstay of the economy. This trend has continued today and in the late 1980s the agricultural sector generally accounted for 48 percent of the nation's employment, 23 percent of GDP, and 98 percent of export earnings. The sector comprised a strong food and cash crop base, a large livestock subsector including cattle ranching and beef production, and a vibrant timber industry.

Agriculture plays a crucial role in the lives of Zimbabweans in rural and urban areas. Most of the people in rural areas survive on agriculture and they need support for them to get good yields.

Agriculture in Panama is an important sector of the Panamanian economy. Major agricultural products include bananas, cocoa beans, coffee, coconuts, timber, beef, chicken, shrimp, corn, potatoes, rice, soybeans, and sugar cane.

Agriculture in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is an industry in the country of the Democratic Republic of the Congo that has plenty of potential.

Agriculture is the main part of Tanzania's economy. As of 2016, Tanzania had over 44 million hectares of arable land with only 33 percent of this amount in cultivation. Almost 70 percent of the rich population live in rural areas, and almost all of them are involved in the farming sector. Land is a vital asset in ensuring food security, and among the nine main food crops in Tanzania are maize, sorghum, millet, rice, wheat, beans, cassava, potatoes, and bananas. The agricultural industry makes a large contribution to the country's foreign exchange earnings, with more than US$1 billion in earnings from cash crop exports.