Anatomy is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its beginnings in prehistoric times. Anatomy is inherently tied to developmental biology, embryology, comparative anatomy, evolutionary biology, and phylogeny, as these are the processes by which anatomy is generated, both over immediate and long-term timescales. Anatomy and physiology, which study the structure and function of organisms and their parts respectively, make a natural pair of related disciplines, and are often studied together. Human anatomy is one of the essential basic sciences that are applied in medicine, and is often studied alongside physiology.

Histology, also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology that studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at larger structures visible without a microscope. Although one may divide microscopic anatomy into organology, the study of organs, histology, the study of tissues, and cytology, the study of cells, modern usage places all of these topics under the field of histology. In medicine, histopathology is the branch of histology that includes the microscopic identification and study of diseased tissue. In the field of paleontology, the term paleohistology refers to the histology of fossil organisms.

Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle was a German physician, pathologist, and anatomist. He is credited with the discovery of the loop of Henle in the kidney. His essay, "On Miasma and Contagia," was an early argument for the germ theory of disease. He was an important figure in the development of modern medicine.

Carl Gegenbaur was a German anatomist and professor who demonstrated that the field of comparative anatomy offers important evidence supporting of the theory of evolution. As a professor of anatomy at the University of Jena (1855–1873) and at the University of Heidelberg (1873–1903), Carl Gegenbaur was a strong supporter of Charles Darwin's theory of organic evolution, having taught and worked, beginning in 1858, with Ernst Haeckel, eight years his junior.

Ádám Politzer was a Hungarian and Austrian physician and one of the pioneers and founders of otology.

In cellular neuroscience, Nissl bodies are discrete granular structures in neurons that consist of rough endoplasmic reticulum, a collection of parallel, membrane-bound cisternae studded with ribosomes on the cytosolic surface of the membranes. Nissl bodies were named after Franz Nissl, a German neuropathologist who invented the staining method bearing his name. The term "Nissl bodies" generally refers to discrete clumps of rough endoplasmic reticulum and free ribosomes in nerve cells. Masses of rough endoplasmic reticulum also occur in some non-neuronal cells, where they are referred to as ergastoplasm, basophilic bodies, or chromophilic substance. While these organelles differ in some ways from Nissl bodies in neurons, large amounts of rough endoplasmic reticulum are generally linked to the copious production of proteins.

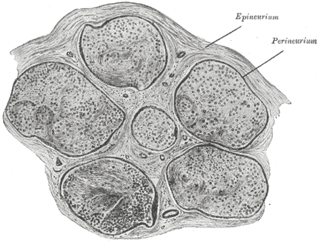

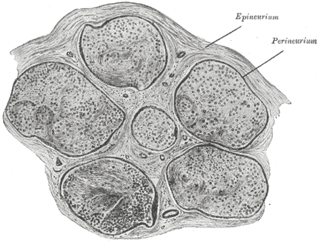

The endoneurium is a layer of delicate connective tissue around the myelin sheath of each myelinated nerve fiber in the peripheral nervous system. Its component cells are called endoneurial cells. The endoneuria with their enclosed nerve fibers are bundled into groups called nerve fascicles, each fascicle within its own protective sheath called a perineurium. In sufficiently large nerves multiple fascicles, each with its blood supply and fatty tissue, may be bundled within yet another sheath, the epineurium.

Franz von Leydig, also Franz Leydig, was a German zoologist and comparative anatomist.

Heinrich Müller was a German anatomist and professor at the University of Würzburg. He is best known for his work in comparative anatomy and his studies involving the eye.

Vladimir Alexeyevich Betz, also Volodymyr Oleksiyovych Betz was a Russian and Ukrainian anatomist and histologist, served as a professor at the Saint Vladimir University of Kyiv.

Martin Heidenhain was a German anatomist born in Breslau. His father was physiologist Rudolf Heidenhain (1834-1937), and his mother, Fanny Volkmann, was the daughter of anatomist Alfred Wilhelm Volkmann (1800-1877).

Eusebio Oehl was an Italian histologist and physiologist who was a native of Lodi.

Anton Gilbert Victor von Ebner, Ritter von Rofenstein was an Austrian anatomist and histologist.

Karl Joseph Eberth was a German pathologist and bacteriologist who was a native of Würzburg.

Mihály Lenhossék, named often given as Michael von Lenhossék was a Hungarian anatomist and histologist born in Budapest. He was the son of anatomist József Lenhossék (1818–1888) and an uncle to Albert Szent-Györgyi (1893–1986).

Giuseppe Vincenzo Ciaccio was an Italian anatomist and histologist. His name is associated with accessory lacrimal glands known as "Ciaccio's glands".

Philipp Stöhr was a German anatomist and histologist.

The Röntgen Memorial Site in Würzburg, Germany, is dedicated to the work of the German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845–1923) and his discovery of X-rays, for which he was granted the Nobel Prize in physics. It contains an exhibition of historical instruments, machines and documents.

Alexander Stanislavovich Dogiel or Dogel, was a Russian Empire histologist and neuroscientist. He contributed to a morphological classification of nerve cells. The cells of Dogiel, bipolar neurons of the spinal ganglia, are named after him.

Henryk Ferdynand Hoyer was a Polish zoologist and professor of comparative anatomy at the Jagiellonian University from 1894 to 1934 serving also as its rector. He is sometimes referred to as Henryk Hoyer junior to differentiate him from his father, Henryk Frederyk Hoyer (1834-1907), who is considered the founder of histology in Poland.