A brain tumor occurs when a group of cells within the brain turn cancerous and grow out of control, creating a mass. There are two main types of tumors: malignant (cancerous) tumors and benign (non-cancerous) tumors. These can be further classified as primary tumors, which start within the brain, and secondary tumors, which most commonly have spread from tumors located outside the brain, known as brain metastasis tumors. All types of brain tumors may produce symptoms that vary depending on the size of the tumor and the part of the brain that is involved. Where symptoms exist, they may include headaches, seizures, problems with vision, vomiting and mental changes. Other symptoms may include difficulty walking, speaking, with sensations, or unconsciousness.

A sarcoma is a malignant tumor, a type of cancer that arises from cells of mesenchymal origin. Connective tissue is a broad term that includes bone, cartilage, muscle, fat, vascular, or other structural tissues, and sarcomas can arise in any of these types of tissues. As a result, there are many subtypes of sarcoma, which are classified based on the specific tissue and type of cell from which the tumor originates.

Endometrial cancer is a cancer that arises from the endometrium. It is the result of the abnormal growth of cells that have the ability to invade or spread to other parts of the body. The first sign is most often vaginal bleeding not associated with a menstrual period. Other symptoms include pain with urination, pain during sexual intercourse, or pelvic pain. Endometrial cancer occurs most commonly after menopause.

Ovarian cancer is a cancerous tumor of an ovary. It may originate from the ovary itself or more commonly from communicating nearby structures such as fallopian tubes or the inner lining of the abdomen. The ovary is made up of three different cell types including epithelial cells, germ cells, and stromal cells. When these cells become abnormal, they have the ability to divide and form tumors. These cells can also invade or spread to other parts of the body. When this process begins, there may be no or only vague symptoms. Symptoms become more noticeable as the cancer progresses. These symptoms may include bloating, vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, abdominal swelling, constipation, and loss of appetite, among others. Common areas to which the cancer may spread include the lining of the abdomen, lymph nodes, lungs, and liver.

Head and neck cancer is a general term encompassing multiple cancers that can develop in the head and neck region. These include cancers of the mouth, tongue, gums and lips, voice box (laryngeal), throat, salivary glands, nose and sinuses.

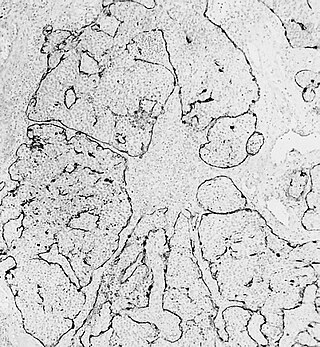

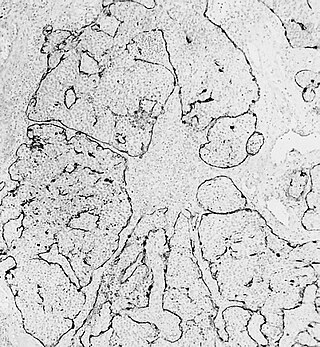

Oligodendrogliomas are a type of glioma that are believed to originate from the oligodendrocytes of the brain or from a glial precursor cell. They occur primarily in adults but are also found in children.

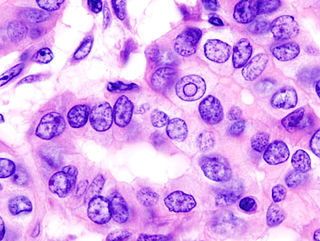

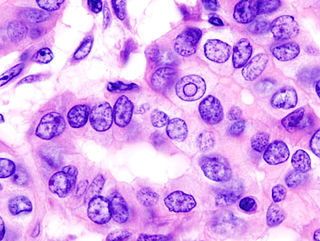

Small-cell carcinoma is a type of highly malignant cancer that most commonly arises within the lung, although it can occasionally arise in other body sites, such as the cervix, prostate, and gastrointestinal tract. Compared to non-small cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma is more aggressive, with a shorter doubling time, higher growth fraction, and earlier development of metastases.

Invasive carcinoma of no special type, invasive breast carcinoma of no special type (IBC-NST), invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) or invasive ductal carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS) is a disease. For international audiences this article will use "invasive carcinoma NST" because it is the preferred term of the World Health Organization (WHO).

A hemangiopericytoma is a type of soft-tissue sarcoma that originates in the pericytes in the walls of capillaries. When inside the nervous system, although not strictly a meningioma tumor, it is a meningeal tumor with a special aggressive behavior. It was first characterized in 1942.

Papillary thyroid cancer is the most common type of thyroid cancer, representing 75 percent to 85 percent of all thyroid cancer cases. It occurs more frequently in women and presents in the 20–55 year age group. It is also the predominant cancer type in children with thyroid cancer, and in patients with thyroid cancer who have had previous radiation to the head and neck. It is often well-differentiated, slow-growing, and localized, although it can metastasize.

Vulvar cancer is a cancer of the vulva, the outer portion of the female genitals. It most commonly affects the labia majora. Less often, the labia minora, clitoris, or Bartholin's glands are affected. Symptoms include a lump, itchiness, changes in the skin, or bleeding from the vulva.

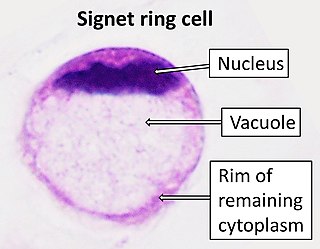

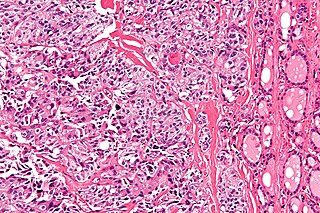

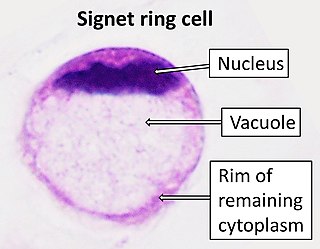

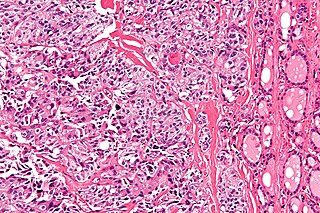

Signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) is a rare form of highly malignant adenocarcinoma that produces mucin. It is an epithelial malignancy characterized by the histologic appearance of signet ring cells.

Cancer of unknown primary origin (CUP) is a cancer that is determined to be at the metastatic stage at the time of diagnosis, but a primary tumor cannot be identified. A diagnosis of CUP requires a clinical picture consistent with metastatic disease and one or more biopsy results inconsistent with a tumor cancer.

Medullary thyroid cancer is a form of thyroid carcinoma which originates from the parafollicular cells, which produce the hormone calcitonin. Medullary tumors are the third most common of all thyroid cancers and together make up about 3% of all thyroid cancer cases. MTC was first characterized in 1959.

Esthesioneuroblastoma is a rare cancer of the nasal cavity. Arising from the upper nasal tract, esthesioneuroblastoma is believed to originate from sensory neuroepithelial cells, also known as neuroectodermal olfactory cells.

Thyroid cancer is cancer that develops from the tissues of the thyroid gland. It is a disease in which cells grow abnormally and have the potential to spread to other parts of the body. Symptoms can include swelling or a lump in the neck, difficulty swallowing or voice changes including hoarseness, or a feeling of something being in the throat due to mass effect from the tumor. However, most cases are asymptomatic. Cancer can also occur in the thyroid after spread from other locations, in which case it is not classified as thyroid cancer.

Human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer, is a cancer of the throat caused by the human papillomavirus type 16 virus (HPV16). In the past, cancer of the oropharynx (throat) was associated with the use of alcohol or tobacco or both, but the majority of cases are now associated with the HPV virus, acquired by having oral contact with the genitals of a person who has a genital HPV infection. Risk factors include having a large number of sexual partners, a history of oral-genital sex or anal–oral sex, having a female partner with a history of either an abnormal Pap smear or cervical dysplasia, having chronic periodontitis, and, among men, younger age at first intercourse and a history of genital warts. HPV-positive OPC is considered a separate disease from HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer.

A brain metastasis is a cancer that has metastasized (spread) to the brain from another location in the body and is therefore considered a secondary brain tumor. The metastasis typically shares a cancer cell type with the original site of the cancer. Metastasis is the most common cause of brain cancer, as primary tumors that originate in the brain are less common. The most common sites of primary cancer which metastasize to the brain are lung, breast, colon, kidney, and skin cancer. Brain metastases can occur months or even years after the original or primary cancer is treated. Brain metastases have a poor prognosis for cure, but modern treatments allow patients to live months and sometimes years after the diagnosis.

Carcinoma of the tonsil is a type of squamous cell carcinoma. The tonsil is the most common site of squamous cell carcinoma in the oropharynx. It comprises 23.1% of all malignancies of the oropharynx. The tumors frequently present at advanced stages, and around 70% of patients present with metastasis to the cervical lymph nodes. . The most reported complaints include sore throat, otalgia or dysphagia. Some patients may complain of feeling the presence of a lump in the throat. Approximately 20% patients present with a node in the neck as the only symptom.

Ovarian squamous cell carcinoma (oSCC) or squamous ovarian carcinoma (SOC) is a rare tumor that accounts for 1% of ovarian cancers. Included in the World Health Organization's classification of ovarian cancer, it mainly affects women above 45 years of age. Survival depends on how advanced the disease is and how different or similar the individual cancer cells are.