| Pituitary adenoma | |

|---|---|

| |

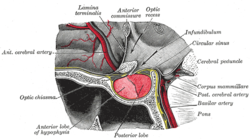

| Visual field loss in bitemporal hemianopsia : peripheral vision loss affecting both eyes, resulting from a tumor – typically a pituitary adenoma – putting pressure on the optic chiasm | |

| Specialty | Oncology, endocrinology |

A pituitary adenoma is a tumor that occurs in the pituitary gland. Most pituitary tumors are benign, approximately 35% are invasive and just 0.1% to 0.2% are carcinomas. [1] Pituitary adenomas represent from 10% to 25% of all intracranial neoplasms, with an estimated prevalence rate in the general population of approximately 17%. [1] [2]

Contents

- Signs and symptoms

- Physical

- Psychiatric

- Complications

- Risk factors

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia

- Carney complex

- Familial isolated pituitary adenoma

- Mechanism

- Diagnosis

- Classification

- Treatment

- See also

- References

- External links

Non-invasive and non-secreting pituitary adenomas are considered to be benign in the literal as well as the clinical sense, though a 2011 meta-analysis of available research showed that research to either support or refute this assumption was scant and of questionable quality. [3]

Adenomas exceeding 10 mm (0.39 in) in size are defined as macroadenomas, while those smaller than 10 mm (0.39 in) are referred to as microadenomas. Most pituitary adenomas are microadenomas and have an estimated prevalence of 16.7% (14.4% in autopsy studies and 22.5% in radiologic studies). [2] [4] The majority of pituitary microadenomas remain undiagnosed, and those that are diagnosed are often found as an incidental finding and are referred to as incidentalomas .

Pituitary macroadenomas are the most common cause of hypopituitarism. [5] [6]

While pituitary adenomas are common, affecting approximately 1 in 6 members of the general population, clinically active pituitary adenomas that require surgical treatment are more rare, affecting approximately 1 in 1,000. [7]