A mold or mould is one of the structures that certain fungi can form. The dust-like, colored appearance of molds is due to the formation of spores containing fungal secondary metabolites. The spores are the dispersal units of the fungi. Not all fungi form molds. Some fungi form mushrooms; others grow as single cells and are called microfungi.

Aspergillus fumigatus is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus, and is one of the most common Aspergillus species to cause disease in individuals with an immunodeficiency.

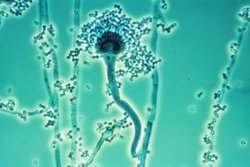

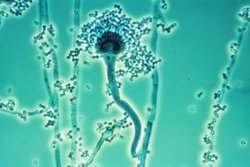

Aspergillus is a genus consisting of several hundred mold species found in various climates worldwide.

Mycotoxicology is the branch of mycology that focuses on analyzing and studying the toxins produced by fungi, known as mycotoxins. In the food industry it is important to adopt measures that keep mycotoxin levels as low as practicable, especially those that are heat-stable. These chemical compounds are the result of secondary metabolism initiated in response to specific developmental or environmental signals. This includes biological stress from the environment, such as lower nutrients or competition for those available. Under this secondary path the fungus produces a wide array of compounds in order to gain some level of advantage, such as incrementing the efficiency of metabolic processes to gain more energy from less food, or attacking other microorganisms and being able to use their remains as a food source.

Aspergillus terreus, also known as Aspergillus terrestris, is a fungus (mold) found worldwide in soil. Although thought to be strictly asexual until recently, A. terreus is now known to be capable of sexual reproduction. This saprotrophic fungus is prevalent in warmer climates such as tropical and subtropical regions. Aside from being located in soil, A. terreus has also been found in habitats such as decomposing vegetation and dust. A. terreus is commonly used in industry to produce important organic acids, such as itaconic acid and cis-aconitic acid, as well as enzymes, like xylanase. It was also the initial source for the drug mevinolin (lovastatin), a drug for lowering serum cholesterol.

A fungus is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one of the traditional eukaryotic kingdoms, along with Animalia, Plantae and either Protista or Protozoa and Chromista.

Marine fungi are species of fungi that live in marine or estuarine environments. They are not a taxonomic group, but share a common habitat. Obligate marine fungi grow exclusively in the marine habitat while wholly or sporadically submerged in sea water. Facultative marine fungi normally occupy terrestrial or freshwater habitats, but are capable of living or even sporulating in a marine habitat. About 444 species of marine fungi have been described, including seven genera and ten species of basidiomycetes, and 177 genera and 360 species of ascomycetes. The remainder of the marine fungi are chytrids and mitosporic or asexual fungi. Many species of marine fungi are known only from spores and it is likely a large number of species have yet to be discovered. In fact, it is thought that less than 1% of all marine fungal species have been described, due to difficulty in targeting marine fungal DNA and difficulties that arise in attempting to grow cultures of marine fungi. It is impracticable to culture many of these fungi, but their nature can be investigated by examining seawater samples and undertaking rDNA analysis of the fungal material found.

Aspergillus ochraceus is a mold species in the genus Aspergillus known to produce the toxin ochratoxin A, one of the most abundant food-contaminating mycotoxins, and citrinin. It also produces the dihydroisocoumarin mellein. It is a filamentous fungus in nature and has characteristic biseriate conidiophores. Traditionally a soil fungus, has now began to adapt to varied ecological niches, like agricultural commodities, farmed animal and marine species. In humans and animals the consumption of this fungus produces chronic neurotoxic, immunosuppressive, genotoxic, carcinogenic and teratogenic effects. Its airborne spores are one of the potential causes of asthma in children and lung diseases in humans. The pig and chicken populations in the farms are the most affected by this fungus and its mycotoxins. Certain fungicides like mancozeb, copper oxychloride, and sulfur have inhibitory effects on the growth of this fungus and its mycotoxin producing capacities.

Aspergillus versicolor is a slow-growing species of filamentous fungus commonly found in damp indoor environments and on food products. It has a characteristic musty odor associated with moldy homes and is a major producer of the hepatotoxic and carcinogenic mycotoxin sterigmatocystin. Like other Aspergillus species, A. versicolor is an eye, nose, and throat irritant.

Aspergillus candidus is a white-spored species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus. Despite its lack of pigmentation, it is closely related to the most darkly-pigmented aspergilli in the Aspergillus niger group. It is a common soil fungus worldwide and is known as a contaminant of a wide array of materials from the indoor environment to foods and products. It is an uncommon agent of onychomycosis and aspergillosis. The species epithet candidus (L.) refers to the white pigmentation of colonies of this fungus. It is from the Candidi section. The fungi in the Candidi section are known for their white spores. It has been isolated from wheat flour, djambee, and wheat grain.

Penicillium citrinum is an anamorph, mesophilic fungus species of the genus of Penicillium which produces tanzawaic acid A-D, ACC, Mevastatin, Quinocitrinine A, Quinocitrinine B, and nephrotoxic citrinin. Penicillium citrinum is often found on moldy citrus fruits and occasionally it occurs in tropical spices and cereals. This Penicillium species also causes mortality for the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus. Because of its mesophilic character, Penicillium citrinum occurs worldwide. The first statin (Mevastatin) was 1970 isolated from this species.

Aspergillus austroafricanus is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus. It is from the Versicolores section. The species was first described in 2012. It has been isolated in South Africa.

Thermomyces lanuginosus is a species of thermophilic fungus that belongs to Thermomyces, a genus of hemicellulose degraders. It is classified as a deuteromycete and no sexual form has ever been observed. It is the dominant fungus of compost heaps, due to its ability to withstand high temperatures and use complex carbon sources for energy. As the temperature of compost heaps rises and the availability of simple carbon sources decreases, it is able to out compete pioneer microflora. It plays an important role in breaking down the hemicelluloses found in plant biomass due to the many hydrolytic enzymes that it produces, such as lipolase, amylase, xylanase, phytase, and chitinase. These enzymes have chemical, environmental, and industrial applications due to their hydrolytic properties. They are used in the food, petroleum, pulp and paper, and animal feed industries, among others. A few rare cases of endocarditis due to T. lanuginosus have been reported in humans.

Aspergillus alabamensis is a soil fungus in the division Ascomycota first described in 2009 as a segregated taxon of A. terreus. Originally thought to be a variant of A. terreus, A. alabamensis is situated in a distinctive clade identified by genetic analysis. While A. alabamensis has been found to be morphologically similar to Aspergillus terreus by morphological studies, the two differ significantly in active metabolic pathways, with A. alabamensis producing the mycotoxins citrinin and citreoviridin but lacking mevinolin.

Aspergillus parasiticus is a fungus belonging to the genus Aspergillus. This species is an unspecialized saprophytic mold, mostly found outdoors in areas of rich soil with decaying plant material as well as in dry grain storage facilities. Often confused with the closely related species, A. flavus, A. parasiticus has defined morphological and molecular differences. Aspergillus parasiticus is one of three fungi able to produce the mycotoxin, aflatoxin, one of the most carcinogenic naturally occurring substances. Environmental stress can upregulate aflatoxin production by the fungus, which can occur when the fungus is growing on plants that become damaged due to exposure to poor weather conditions, during drought, by insects, or by birds. In humans, exposure to A. parasiticus toxins can cause delayed development in children and produce serious liver diseases and/or hepatic carcinoma in adults. The fungus can also cause the infection known as aspergillosis in humans and other animals. A. parasiticus is of agricultural importance due to its ability to cause disease in corn, peanut, and cottonseed.

Aspergillus flavipes is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus. It is from the Flavipedes section. The species was first described in 1926. It has been reported to produce sterigmatocystin, citrinin, and lovastatin.

Aspergillus wentii is an asexual, filamentous, endosymbiotic fungus belonging to the mold genus, Aspergillus. It is a common soil fungus with a cosmopolitan distribution, although it is primarily found in subtropical regions. Found on a variety of organic materials, A. wentii is known to colonize corn, cereals, moist grains, peanuts and other ground nut crops. It is also used in the manufacture of biodiesel from lipids and is known for its ability to produce enzymes used in the food industry.

Aspergillus hortai is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus. It is from the Terrei section. The species was first described in 1935. It has been isolated from the ear of a human in Brazil, soil from the Galapagos Islands, and soil from the United States. It has been reported to produce acetylaranotin, butyrolactones, citrinin, 3-methylorsellinic acid, terrein, and terrequinone A.

Pestalotiopsis pauciseta is an endophytic fungi isolated from the leaves of several medicinal plants in tropical climates. Pestalotiopsis pauciseta is known for its role in medical mycology, having the ability to produce a chemical compound called paclitaxel (taxol). Taxol is the first billion-dollar anticancer drug, notably the fungal-taxol produced by Pestalotiopsis pauciseta was determined to be comparable to standard taxol.

Circumdati is a subgenus of Aspergillus in the family Trichocomaceae.