Clearfield County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 80,562. The county seat is Clearfield, and the largest city is DuBois. The county was created in 1804 and later organized in 1822.

Clearfield is a borough and the county seat of Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 census the population was 5,962 people, making it the second most populous community in Clearfield County, behind DuBois. The borough is part of the DuBois, PA Micropolitan Statistical Area, as well as the larger State College-DuBois, PA Combined Statistical Area. The settled area surrounding the borough consists of the nearby census-designated places of Hyde and Plymptonville, which combined with Clearfield have a population of approximately 8,237 people.

Curwensville is a borough in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, United States, 45 miles (72 km) north of Altoona on the West Branch Susquehanna River. Coal mining, tanning, and the manufacture of fire bricks were the industries at the turn of the 20th century. In 1900, 1,937 people lived in the borough, and in 1910, 2,549 lived there. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the borough had a population of 2,570. The population of the borough at its highest was 3,422 in 1940.

Grampian is a borough in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 358 as of the 2020 census.

The Juniata River is a tributary of the Susquehanna River, approximately 104 miles (167 km) long, in central Pennsylvania. The river is considered scenic along much of its route, having a broad and shallow course passing through several mountain ridges and steeply lined water gaps. It formed an early 18th-century frontier region in Pennsylvania and was the site of French-allied Native American attacks against English colonial settlements during the French and Indian War.

The West Branch Susquehanna River is one of the two principal branches, along with the North Branch, of the Susquehanna River in the Northeastern United States. The North Branch, which rises in upstate New York, is generally regarded as the extension of the main branch, with the shorter West Branch being its principal tributary.

Anderson Creek is a 23.6-mile-long (38.0 km) tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, in the United States.

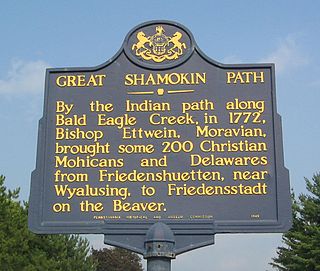

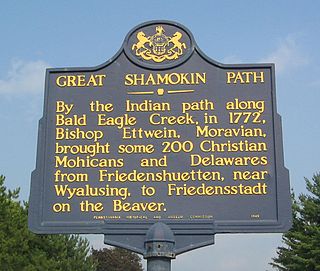

The Great Shamokin Path was a major Native American trail in the U.S. State of Pennsylvania that ran from the native village of Shamokin along the left bank of the West Branch Susquehanna River north and then west to the Great Island. There it left the river and continued further west to Chinklacamoose and finally Kittanning on the Allegheny River.

Black Moshannon State Park is a 3,480-acre (1,410 ha) Pennsylvania state park in Rush Township, Centre County, Pennsylvania, United States. It surrounds Black Moshannon Lake, formed by a dam on Black Moshannon Creek, which has given its name to the lake and park. The park is just west of the Allegheny Front, 9 miles (14 km) east of Philipsburg on Pennsylvania Route 504, and is largely surrounded by Moshannon State Forest. A bog in the park provides a habitat for diverse wildlife not common in other areas of the state, such as carnivorous plants, orchids, and species normally found farther north. As home to the "largest reconstituted bog in Pennsylvania", it was chosen by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources for its "25 Must-see Pennsylvania State Parks" list.

Sinnemahoning State Park is a 1,910-acre (773 ha) Pennsylvania state park in Grove Township, Cameron County and Wharton Township, Potter County, Pennsylvania, in the United States. The park is surrounded by Elk State Forest and is mountainous with deep valleys. The park is home to the rarely seen elk and bald eagle. Sinnemahoning State Park is on Pennsylvania Route 872, eight miles (13 km) north of the village of Sinnamahoning. In 1958, the park opened under the direction of the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry: it became a Pennsylvania State Park in 1962.

Bucktail State Park Natural Area is a 16,433-acre (6,650 ha) Pennsylvania state park in Cameron and Clinton Counties in Pennsylvania in the United States. The park follows Pennsylvania Route 120 for 75 miles (121 km) between Emporium and Lock Haven. Bucktail State Park Natural Area park runs along Sinnemahoning Creek and the West Branch Susquehanna River and also passes through Renovo. The park is named for the Civil War Pennsylvania Bucktails Regiment and is primarily dedicated to wildlife viewing, especially elk.

Pennsylvania Route 453 is a 43+3⁄4-mile-long (70.4 km) state highway located in Huntingdon, Blair, and Clearfield counties in Pennsylvania. The southern terminus is at U.S. Route 22 (US 22) in Water Street; the northern terminus is at PA 879 in Curwensville.

Pennsylvania Route 879 is a 43-mile-long (69 km) state highway located in Clearfield and Centre Counties in Pennsylvania. The western terminus is at U.S. Route 219 (US 219) and PA 729 in Grampian. The eastern terminus is at PA 144 in Snow Shoe Township.

The Pennsylvanian Pottsville Formation is a mapped bedrock unit in Pennsylvania, western Maryland, West Virginia, Ohio, and Alabama. It is a major ridge-former in the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians of the eastern United States. The Pottsville Formation is conspicuous at many sites along the Allegheny Front, the eastern escarpment of the Allegheny or Appalachian Plateau.

The Pine Creek Path was a major Native American trail in the U.S. State of Pennsylvania that ran north along Pine Creek from the West Branch Susquehanna River near Long Island to the headwaters of the Genesee River.

West Decatur is an unincorporated community and census-designated place in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2010 census the population of West Decatur was 533.

Pennsylvania Route 969 is a 10.4-mile-long (16.7 km) state highway located in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania. The western terminus is at U.S. Route 219 in Greenwood Township. The eastern terminus is at PA 453 in Curwensville. The route is known locally as the Lumber City Highway.

The Big Spring near Luthersburg, Brady Township, Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, was an important camp site and trail hub for the Great Shamokin Path and the Goschgoschink Path.

The gaps of the Allegheny, meaning gaps in the Allegheny Ridge in west-central Pennsylvania, is a series of escarpment eroding water gaps along the saddle between two higher barrier ridge-lines in the eastern face atop the Allegheny Ridge or Allegheny Front escarpment. The front extends south through Western Maryland and forms much of the border between Virginia and West Virginia, in part explaining the difference in cultures between those two post-Civil War states. While not totally impenetrable to daring and energetic travelers on foot, passing the front outside of the water gaps with even sure footed mules was nearly impossible without navigating terrain where climbing was necessary on slopes even burros would find extremely difficult.