Yerevan is the capital and largest city of Armenia, as well as one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerevan is the administrative, cultural, and industrial center of the country, as its primate city. It has been the capital since 1918, the fourteenth in the history of Armenia and the seventh located in or around the Ararat Plain. The city also serves as the seat of the Araratian Pontifical Diocese, which is the largest diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church and one of the oldest dioceses in the world.

The Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic is a landlocked exclave of the Republic of Azerbaijan. The region covers 5,502.75 km2 (2,124.62 sq mi) with a population of 459,600. It is bordered by Armenia to the east and north, Iran to the southwest, and Turkey to the west. It is the sole autonomous republic of Azerbaijan, governed by its own elected legislature.

Islam began to make inroads into the Armenian Plateau during the seventh century. Arab, and later Kurdish, began to settle in Armenia following the first Arab expansion and played a considerable role in the political and social history of Armenia. With the Seljuk invasions of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Turkic element eventually superseded that of the Arab and Kurdish. With the establishment of the Iranian Safavid dynasty, Afsharid dynasty, Zand Dynasty and Qajar dynasty, Armenia became an integral part of the Shia world, while still maintaining a relatively independent Christian identity. The pressures brought upon the imposition of foreign rule by a succession of Muslim states forced many Armenians in Anatolia and what is today Armenia to convert to Islam and assimilate into the Muslim community. Many Armenians were also forced to convert to Islam, on the penalty of death, during the years of the Armenian Genocide.

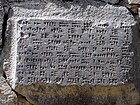

Julfa, formerly Jugha, is a city and the capital of the Julfa District of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic of Azerbaijan.

The Erivan Khanate, also known as Chokhur-e Sa'd, was a khanate that was established in Afsharid Iran in the 18th century. It covered an area of roughly 19,500 km2, and corresponded to most of present-day central Armenia, the Iğdır Province and the Kars Province's Kağızman district in present-day Turkey and the Sharur and Sadarak districts of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic of present-day Azerbaijan.

The Erivan Governorate was a province (guberniya) of the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire, with its centеr in Erivan. Its area was 27,830 sq. kilometеrs, roughly corresponding to what is now most of central Armenia, the Iğdır Province of Turkey, and the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan. At the end of the 19th century, it bordered the Tiflis Governorate to the north, the Elizavetpol Governorate to the east, the Kars Oblast to the west, and Persia and the Ottoman Empire to the south. Mount Ararat and the fertile Ararat Valley were included in the center of the province.

Bilateral relations exist between Armenia and Iran. Despite religious and ideological differences, relations between the two states remain extensively cordial and both are strategic partners in the region. Armenia and Iran are both neighbouring countries in Western Asia and share a common land border that is 44 kilometres (27 mi) in length.

Bilateral relations between modern-day Armenia and the Russian Federation were established on 3 April 1992, though Russia has been an important actor in Armenia since the early 19th century. The two countries' historic relationship has its roots in the Russo-Persian War of 1826 to 1828 between the Russian Empire and Qajar Persia after which Eastern Armenia was ceded to Russia. Moreover, Russia was viewed as a protector of the Christian subjects in the Ottoman Empire, including the Armenians.

Azerbaijanis in Armenia numbered 29 people according to the 2001 census of Armenia. Although they have previously been the biggest minority in the country according to 1831–1989 censuses, they are virtually non-existent since 1988–1991 when most fled or were forced out of the country as a result of the tensions of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War to neighboring Azerbaijan. The UNHCR estimates that the current population of Azerbaijanis in Armenia to be somewhere between 30 and a few hundred people, with most of them living in rural areas as members of mixed couples, as well as elderly or sick. Most of them are reported to have changed their names to maintain a low profile to avoid discrimination.

Nikol Vovayi Pashinyan is an Armenian politician serving as the prime minister of Armenia since 8 May 2018. A journalist by profession, Pashinyan founded his own newspaper in 1998, which was shut down a year later for libel. He was sentenced for one year for defamation against then Minister of National Security Serzh Sargsyan. He edited the newspaper Haykakan Zhamanak from 1999 to 2012. A supporter of Armenia's first president Levon Ter-Petrosyan, he was highly critical of second president Robert Kocharyan, Defense Minister Serzh Sargsyan, and their allies. Pashinyan was also critical of Armenia's close relations with Russia, and promoted establishing closer relations with Turkey instead. He led a minor opposition party in the 2007 parliamentary election, garnering 1.3% of the vote.

Erivan Fortress or Yerevan Fortress was a 16th-century fortress in Yerevan.

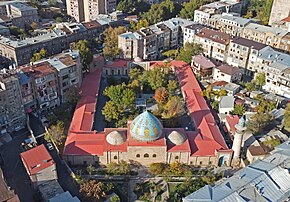

Abbas Mirza Mosque was a nineteenth-century Shia mosque in Yerevan, Armenia. Abbas Mirza, in the eighteenth century, the castle was built near the mosque in Yerevan. This mosque was built at the beginning of the nineteenth century, during the reign of the last khan (governor) of the Erivan Khanate, Huseyn Khan. It was named Abbas Mirza Jami, after the Qajar crown prince Abbas Mirza, the son of Fat′h-Ali Shah. The façade of mosque was covered in green and blue glass, reflecting Persian architectural styles. After the Capture of Erivan by the Russians, the mosque was used as an arsenal. The mosque was turned into barracks after it was conquered by Russian troops.

Western Azerbaijan is an irredentist political concept that is used in the Republic of Azerbaijan mostly to refer to the territory of the Republic of Armenia. Azerbaijani officials claim that the territory of the modern Armenian republic were lands that once belonged to Azerbaijanis. Its claims are primarily hinged over the contention that the current Armenian territory was under the rule of various Turkic tribes, empires and khanates from the Late Middle Ages until the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828) signed after the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828. The concept has received official endorsement by the government of Azerbaijan, and has been used by its current president, Ilham Aliyev, who, since around 2010, has made regular reference to "Irevan" (Yerevan), "Göyçə" and "Zangazur" (Syunik) as once and future "Azerbaijani lands". The irredentist concept of "Western Azerbaijan" is associated with other irredentist claims promoted by Azerbaijani officials and academics, including the "Goycha-Zangazur Republic" and the "Republic of Irevan."

The anti-Azerbaijani sentiment, or anti-Azerbaijanism has been mainly rooted in several countries, most notably in Russia, Armenia and Iran, where anti-Azerbaijani sentiment has sometimes led to violent ethnic incidents.

The European Party of Armenia (EPA) is a pro-European political party in Armenia. It was founded on 6 November 2018 by filmmaker Tigran Khzmalyan.

The Adequate Party is an Armenian far-right political party.

Armenia and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have maintained a formal relationship since 1992, when Armenia joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council. Armenia officially established bilateral relations with NATO in 1994 when it became a member of NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme. In 2002, Armenia became an Associate Member of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.

The 2022 Armenian protests were a series of anti-government protests in Armenia that started on 5 April 2022. The protests continued into June 2022, and many protesters were detained by police in Yerevan. Protestors demanded Prime Minister of Armenia Nikol Pashinyan resign over his handling of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. On 14 June 2022, the opposition announced their decision to terminate daily demonstrations aimed at toppling Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan after failing to achieve popular support.

On 12 September 2022, a series of clashes erupted between Armenian and Azerbaijani troops along the Armenia–Azerbaijan border, marking a major escalation in the current border crisis between Armenia–Azerbaijan and resulting in nearly 300 deaths and dozens of injuries on both sides by 14 September. A number of human rights organizations and governments – including the United States, European Parliament, Canada, France, Uruguay, Cyprus – stated that Azerbaijan had launched an attack on positions inside the Republic of Armenia.