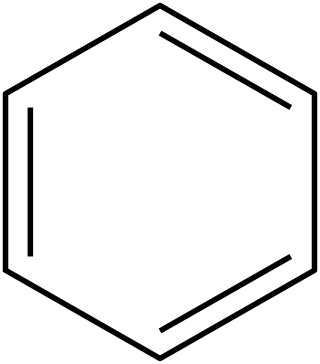

Aromatic compounds or arenes usually refers to organic compounds "with a chemistry typified by benzene" and "cyclically conjugated." The word "aromatic" originates from the past grouping of molecules based on odor, before their general chemical properties were understood. The current definition of aromatic compounds does not have any relation to their odor. Aromatic compounds are now defined as cyclic compounds satisfying Hückel's Rule. Aromatic compounds have the following general properties:

In organic chemistry, the phenyl group, or phenyl ring, is a cyclic group of atoms with the formula C6H5, and is often represented by the symbol Ph. The phenyl group is closely related to benzene and can be viewed as a benzene ring, minus a hydrogen, which may be replaced by some other element or compound to serve as a functional group. A phenyl group has six carbon atoms bonded together in a hexagonal planar ring, five of which are bonded to individual hydrogen atoms, with the remaining carbon bonded to a substituent. Phenyl groups are commonplace in organic chemistry. Although often depicted with alternating double and single bonds, the phenyl group is chemically aromatic and has equal bond lengths between carbon atoms in the ring.

An acetylcholine receptor or a cholinergic receptor is an integral membrane protein that responds to the binding of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter.

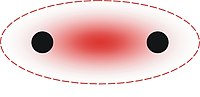

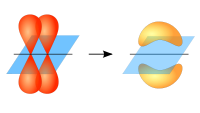

In theoretical chemistry, a conjugated system is a system of connected p-orbitals with delocalized electrons in a molecule, which in general lowers the overall energy of the molecule and increases stability. It is conventionally represented as having alternating single and multiple bonds. Lone pairs, radicals or carbenium ions may be part of the system, which may be cyclic, acyclic, linear or mixed. The term "conjugated" was coined in 1899 by the German chemist Johannes Thiele.

In organic chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property describing the way in which a conjugated ring of unsaturated bonds, lone pairs, or empty orbitals exhibits a stabilization stronger than would be expected by the stabilization of conjugation alone. The earliest use of the term was in an article by August Wilhelm Hofmann in 1855. There is no general relationship between aromaticity as a chemical property and the olfactory properties of such compounds.

In electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions, existing substituent groups on the aromatic ring influence the overall reaction rate or have a directing effect on positional isomer of the products that are formed.

In organic chemistry, Hückel's rule predicts that a planar ring molecule will have aromatic properties if it has 4n + 2 π-electrons, where n is a non-negative integer. The quantum mechanical basis for its formulation was first worked out by physical chemist Erich Hückel in 1931. The succinct expression as the 4n + 2 rule has been attributed to W. v. E. Doering (1951), although several authors were using this form at around the same time.

A nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) is a substitution reaction in organic chemistry in which the nucleophile displaces a good leaving group, such as a halide, on an aromatic ring. Aromatic rings are usually nucleophilic, but some aromatic compounds do undergo nucleophilic substitution. Just as normally nucleophilic alkenes can be made to undergo conjugate substitution if they carry electron-withdrawing substituents, so normally nucleophilic aromatic rings also become electrophilic if they have the right substituents.

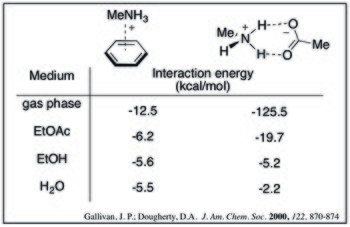

In chemistry, a non-covalent interaction differs from a covalent bond in that it does not involve the sharing of electrons, but rather involves more dispersed variations of electromagnetic interactions between molecules or within a molecule. The chemical energy released in the formation of non-covalent interactions is typically on the order of 1–5 kcal/mol. Non-covalent interactions can be classified into different categories, such as electrostatic, π-effects, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects.

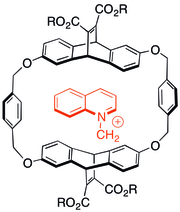

In chemistry, pi stacking refers to the presumptive attractive, noncovalent pi interactions between the pi bonds of aromatic rings. According to some authors direct stacking of aromatic rings is electrostatically repulsive.

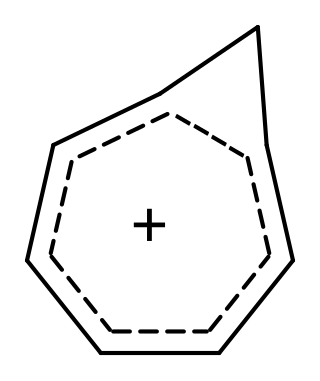

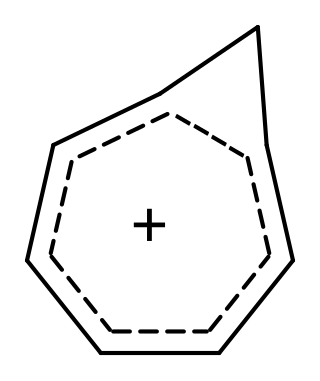

Homoaromaticity, in organic chemistry, refers to a special case of aromaticity in which conjugation is interrupted by a single sp3 hybridized carbon atom. Although this sp3 center disrupts the continuous overlap of p-orbitals, traditionally thought to be a requirement for aromaticity, considerable thermodynamic stability and many of the spectroscopic, magnetic, and chemical properties associated with aromatic compounds are still observed for such compounds. This formal discontinuity is apparently bridged by p-orbital overlap, maintaining a contiguous cycle of π electrons that is responsible for this preserved chemical stability.

In organic chemistry, the Hammett equation describes a linear free-energy relationship relating reaction rates and equilibrium constants for many reactions involving benzoic acid derivatives with meta- and para-substituents to each other with just two parameters: a substituent constant and a reaction constant. This equation was developed and published by Louis Plack Hammett in 1937 as a follow-up to qualitative observations in his 1935 publication.

The Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel superfamily is composed of nicotinic acetylcholine, GABAA, GABAA-ρ, glycine, 5-HT3, and zinc-activated (ZAC) receptors. These receptors are composed of five protein subunits which form a pentameric arrangement around a central pore. There are usually 2 alpha subunits and 3 other beta, gamma, or delta subunits (some consist of 5 alpha subunits). The name of the family refers to a characteristic loop formed by 13 highly conserved amino acids between two cysteine (Cys) residues, which form a disulfide bond near the N-terminal extracellular domain.

Physical organic chemistry, a term coined by Louis Hammett in 1940, refers to a discipline of organic chemistry that focuses on the relationship between chemical structures and reactivity, in particular, applying experimental tools of physical chemistry to the study of organic molecules. Specific focal points of study include the rates of organic reactions, the relative chemical stabilities of the starting materials, reactive intermediates, transition states, and products of chemical reactions, and non-covalent aspects of solvation and molecular interactions that influence chemical reactivity. Such studies provide theoretical and practical frameworks to understand how changes in structure in solution or solid-state contexts impact reaction mechanism and rate for each organic reaction of interest.

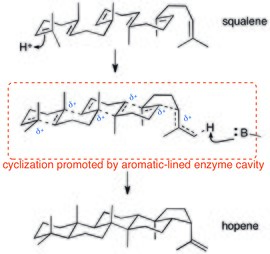

In chemistry, π-effects or π-interactions are a type of non-covalent interaction that involves π systems. Just like in an electrostatic interaction where a region of negative charge interacts with a positive charge, the electron-rich π system can interact with a metal, an anion, another molecule and even another π system. Non-covalent interactions involving π systems are pivotal to biological events such as protein-ligand recognition.

Dennis A. Dougherty is the George Grant Hoag Professor of Chemistry at California Institute of Technology. His research applies physical organic chemistry to systems of biological importance. Dougherty utilizes a variety of approaches to further our understanding of the human brain, including the in vivo nonsense suppression methodology for incorporating unnatural amino acids into a variety of ion channels for structure-function studies.

Electrophilic aromatic substitution (SEAr) is an organic reaction in which an atom that is attached to an aromatic system is replaced by an electrophile. Some of the most important electrophilic aromatic substitutions are aromatic nitration, aromatic halogenation, aromatic sulfonation, alkylation Friedel–Crafts reaction and acylation Friedel–Crafts reaction.

In chemistry, primarily organic and computational chemistry, a stereoelectronic effect is an effect on molecular geometry, reactivity, or physical properties due to spatial relationships in the molecules' electronic structure, in particular the interaction between atomic and/or molecular orbitals. Phrased differently, stereoelectronic effects can also be defined as the geometric constraints placed on the ground and/or transition states of molecules that arise from considerations of orbital overlap. Thus, a stereoelectronic effect explains a particular molecular property or reactivity by invoking stabilizing or destabilizing interactions that depend on the relative orientations of electrons in space.

Among pnictogen group Lewis acidic compounds, unusual lewis acidity of Lewis acidic antimony compounds have long been exploited as both stable conjugate acids of non-coordinating anions, and strong Lewis acid counterparts of well-known superacids. Also, Lewis-acidic antimony compounds have recently been investigated to extend the chemistry of boron because of the isolobal analogy between the vacant p orbital of borane and σ*(Sb–X) orbitals of stiborane, and the similar electronegativities of antimony (2.05) and boron (2.04).

Arene complexes of univalent gallium, indium, and thallium are complexes featuring the centric (η6) coordination of the metal to the arene. Although arene complexes of transitional metals have long been reported, arene complexes of the main group elements remain scarce. This might be partly explained by the difference in energy of the d and p orbitals.

![Fig. 2: The Stoddart synthesis of [2]catenane 24 fig. 2.png](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/15/24_fig._2.png/220px-24_fig._2.png)