Contents

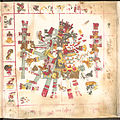

The manuscript comprises 28 sections. [4] [8] Most of them are devoted to the different aspects of the Tonalpohualli , the Central Mexican divinatory calendar. In general, the codex presents the associations between time periods, gods, and 'mantic images', or iconography with a divinatory content. [9] Section 13, which comprises pages 29–46, has been the subject of differing interpretations throughout the years. The one that claims it depicts a series of rituals is the most agreed upon. [1] The overview offered here follows the division proposed by Karl Anton Nowotny. [4]

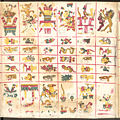

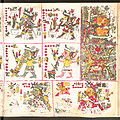

Section 1: Tonalpohualli in extenso (pages 1–8)

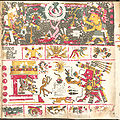

The first eight pages list the 260 day-signs of the tonalpohualli, each trecena or 13-day division forming a horizontal row spanning two pages. Certain days are marked with a footprint symbol with an unknown purpose. Mantic images are placed above and below the day signs. Sections parallel to this one are contained in the first eight pages of the Codex Cospi and the Codex Vaticanus B. However, while the Codex Borgia is read from right to left, those codices are read from left to right. Additionally, the Codex Cospi includes the so-called Lords of the Night alongside the day signs (see Section 3).

- Images of pages 1–8

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

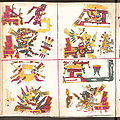

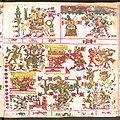

Section 2: The First 20 day signs with their regents Pages (9–13)

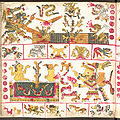

Pages 9 to 13 are divided into four quarters. Each quarter contains one of the twenty day signs, its patron deity, and associated mantic symbols, presumably as prognostications for individuals born in each of those day signs. The list is as follows:

- Cipactli (Caiman), Tonacatecuhtli

- Ehecatl (Wind), Ehecatl

- Calli (House), Tepeyollotl

- Cuetzpalin (Lizard), Huehuecoyotl

- Coatl (Snake), Chalchiuhtlicue

- Miquiztli (Death), Metztli

- Mazatl (Deer), Tlaloc

- Tochtli (Rabbit), Mayahuel

- Atl (Water), Xiuhtecuhtli

- Itzcuintli (Dog), Mictlantecuhtli

- Ozomahtli (Monkey), Xochipilli

- Malinalli (Grass), Patecatl

- Acatl (Reed), Itztlacoliuhqui

- Ocelotl (Jaguar), Tlazolteotl

- Cuauhtli (Eagle), Xipe Totec

- Cozcacuauhtli (Vulture), Itzpapalotl

- Olin (Movement), Xolotl

- Tecpatl (Flint), Chalchiuhtotolin

- Quiyahuitl (Rain), Tonatiuh

- Xochitl (Flower), Xochiquetzal

- Images of pages 9–13

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Section 3: The Lords of the Night (14)

Page 14 is divided into nine sections for each of the nine Lords of the Night, pre-Hispanic deities which ruled nighttime. They are accompanied by a day sign and symbols indicating positive or negative associations. The deities and prognostications according to Codex Ríos and Jacinto de la Serna, a seventeenth-century Spanish cleric, are as follows:

- Xiuhtecuhtli (Ríos: good; de la Serna: bad)

- Tezcatlipoca (Ríos: bad; de la Serna: bad)

- Pilzintecuhtli (Ríos: good; de la Serna: very good)

- Centeotl (Ríos: indifferent; de la Serna: very good)

- Mictlantecuhtli (Ríos: bad; de la Serna: good)

- Chalchiuhtlicue (Ríos: indifferent; de la Serna: very good)

- Tlazolteotl (Ríos: bad; de la Serna: bad)

- Tepeyolotl (Ríos: good; de la Serna: good)

- Tlaloc (Ríos: indifferent; de la Serna: very good) [10]

Section 4 and 5: Mantics referring to children. Tezcatlipoca, lord of fate (15–17)

Pages 15 to 17 depict deities associated with childbirth. Each of the twenty sections contains four day signs. The bottom section of page 17 contains a large depiction of Tezcatlipoca, with day signs associated with different parts of his body.

- Images of pages 15–17

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Section 6: Different prognostications (18–21)

Prognostications related to different activities being performed by gods, including religious activities (Tonatiuh, Ehecatl), woodcutting (Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli), agriculture (Tlaloc), crossing a river (Chalchiuhtlicue) travelling (red Tezcatlipoca), and the ball-game (black Tezcatlipoca).

- Images of pages 18–21

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Section 7 and 8: Wounded deer and the cultic qualities of the 20 day-signs (22–24)

The upper side of page 22 presents two deer, one white, with closed eyes and surrounded by precious regalia, and other being pierced by a dart or arrow, which gives its name to the section. Pages 22–24 present the ritual qualities of the 20 day-signs.

- Images of pages 22–24

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Section 9 and 10: The four quarters and the region of the dead

Two directional almanacs, one depicting four deities (Tlaloc, Xipe Totec, an unidentified Mixtec god, and Mixcoatl), and a directional almanac related to death, associated with four deities.

- Images of pages 25-26

Page 25

Page 26

Section 11 and 12: The rain gods of the 4 quarters and the centre (27–28)

Pages 27 and 28 center on the Postclassical period central Mexican rain god Tlaloc, associated to the 4 quarters and the centre, as well as the qualities of the rains that he will bring, some destructive, some beneficial.

- Images of pages 27-28

Page 27

Page 28

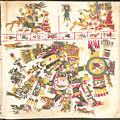

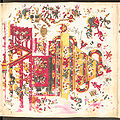

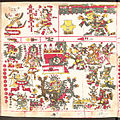

Section 13 (pages 29–46): The Cultic Part

Having no discernible parallels with other manuscripts within the Borgia Group, the interpretation of this section has varied strongly throughout the years. Its first interpreter, the jesuit Lino Fábrega, considered it to be a native Zodiac, divided in 18 signs. [11] Eduard Seler, its first modern interpreter, considered it to be the journey of Venus through the underworld. [12] His astronomical interpretation was continued by his disciple, Friedrich Röck, as well as modern scholars such as Susan Milbrath. [13] It was Karl Anton Nowotny, a disciple of Röck, who first questioned the 'astral interpretation' of Seler's school, partly inspired by Alfonso Caso's work on Mixtec codices, where it was demonstrated that those documents were not astronomical, but historical. [9] Nowotny proposed that each of the 18 pages of this section describes a different ritual, proposing the following internal division: [4]

- Cult of the wind gods (p. 29)

- Cult of the rain gods (p. 30)

- Cult of the maguey (p. 31, above)

- Cult of the corn (p. 31, below)

- Cult of Tezcatlipoca (p. 32)

- The black temple (p. 33)

- The red temple (p. 34)

- Opening of a ritual bundle (p. 33)

- Sacrifice to the sun (p. 39-40)

- Sacrifice to the Cihuapipiltin (pp. 41–42)

- A corn festival (p. 43)

- Enthronement of a prince (p. 44)

- Cult of the Morning Star (p. 45)

- Fire-Drilling (p. 46)

Nowotny's interpretation has become the basis of many subsequent readings, such as those of Ferdinand Anders, Maarten Jansen, and Luis Reyes (1993), who complemented Nowotny's interpretation with ethnographic data and re-interpreted some of the rituals; [3] that of Bruce Byland and John Pohl, who researched the relationship between the rites depicted in this section and the rituals of Mixtec kings; [14] and that of Samantha Gerritse, who offers a narratological analysis. [11] Other diverging models are that offered by Elizabeth Hill Boone, who considers these pages to be a cosmological narrative, [10] and that of Juan José Batalla Rosado, who considers them to be a series of hallucinations that pre-Hispanic priests would have to endure during initiation. [15]

- Images of pages 29–46

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Section 14: The Cihuateteo and the Macuitonaleque (47-48)

This section depicts the Cihuateteo, the divinized spirits of the women that died in child-birth, and the Macuiltonaleque, minor spirits of excess, pleasure and violence.

Section 15, 16, and 17: Directional Almanacs and the 'deer of our flesh' (50-53)

The directional almanacs depict the four quarters of the universe and the centre, and their corresponding day signs, sacred trees, and 'mantic images'. The 'deer of our flesh' or tonacayo mazatl is a corporeal almanac, associating parts of the human body figured as a deer with day-signs. Its meaning is not agreed: according to Codex Tudela, they are mere prognostications for people born at those birth signs, while Codex Rios suggest a medical use.

Section 18: The morning star (53-54)

This section starts in the lower left part of page 53 and continues throughout page 54. It is generally considered, following Seler, that the iconography depicts Venus as the morning star, piercing different characters or iconographic elements in different day-signs. [12] Due to the mechanics of the Tonalpohualli, the heliacal rising of Venus can only happen in five day signs: Crocodile, Snake, Water, Reed and Movement. [16] Thus, the prognostications associated to the rising of the planet in each day, as well as the next three days, are presented. The interpretation of the iconography of each unit has been related to water (Caiman, Wind, House, Lizard), polities (Snake, Death, Deer, Rabbit), earth and agriculture (Water, Dog, Monkey, Grass), rulers (Reed, Jaguar, Eagle and Vulture), and war (Movement, Flint, Storm, Flower). Recently the scholar Ana Díaz has questioned the calendrical mechanism present in these pages, which don't seem to be fit for this astronomical calculation; [17] however, hieroglyphic evidence from Seibal in the Maya area and the heavily Toltec-influenced Maya Codex of Mexico, the oldest Venus almanac in Mesoamerica, suggest that these calculations are central Mexican in origin, rather than Maya. [16]

Section 19: The gods of the merchants (55)

This section depicts day-signs associated to different deities represented as travellers or merchants, and their associated prognostications.

Section 20: The Tonalpohualli divided among Quetzalcoatl and Mictlantecuhtli (56)

This page depicts Mictlantecuhtli and Quetzalcoatl back to back. The purpose is unknown, but perhaps it was related to life and death prognostications in medicine.

Section 21 and 22: Marriage Prognostications

This section comprises prognostications for marriages. The coefficient of the Tonalpohualli birth-sign of the groom and the bride (comprising from 1 to 13) are added, and the resulting sum is compared to each of the images, which go from 2, the lowest result, to 26, the highest. The prognostication is given by the iconography: in general, even numbers are unlucky, odd, lucky.

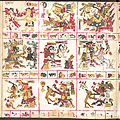

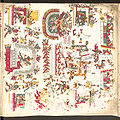

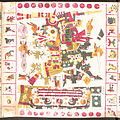

Section 23 and 24: The twenty 13-day 'weeks' or trecenas of the Tonalpohualli, and the auguric birds of each day (61-70)

A complete tonalpohualli, comprising the twenty 13-day periods which were known as trecenas in Spanish, which some chroniclers considered equivalent to weeks in the Gregorian calendar. Each trecena is named after its initial day-sign, and each has a patron god which determines if it is either lucky or unlucky. Trecenas, patron gods and prognostications are the following, according to the glosses in Codex Borbonicus:

- One Caiman, Tonacatecuhtli

- One Jaguar, Ehecatl

- One Deer, Tepeyollotl

- One Flower, Huehuecoyotl

- One Reed, Chalchiuhtlicue

- One Death, Tonatiuh

- One Rain, Tlaloc

- One Grass, Mayahuel

- One Snake, Xiuhtecuhtli

- One Flint, Mictlantecuhtli

- One Monkey, Patecatl

- One Lizard, Ixtlacoliuhqui

- One Movement, Tlazolteotl

- One Dog, Xipe Totec

- One House, Itzpapalotl

- One Vulture, Xolotl

- One Water, Chalchiuhtotolin

- One Wind, Chantico

- One Eagle, Xochiquetzal

- One Rabbit, Xiuhtecuhtli

The final page of this section depicts the sun god, Tonatiuh, receiving offerings, and states the sacred flying animals associated to each day.

- Images of pages 61–71

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Section 25 The 20 'weeks', the quarters of the universe and the centre

This almanac divides the 20 day-signs into quarters associated with deities and snakes forming a xicalcoliuhqui or meandering pattern.

Similar to section 20, but divided in four quarters rather than two halves.

Section 27: 20-day signs referred to men and women

This almanac presents a Cihuapilli and a Macuiltonaleque, each associated with day-signs.

Section 28: Gods of the half-trecenas

This almanac depicts the ruling deities of half-trecena periods, enthroned, receiving cult and with associated mantic images. [10]