Related Research Articles

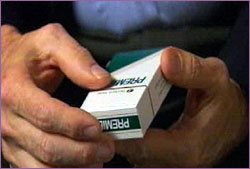

Premier was an American brand of smokeless cigarettes which was owned and manufactured by the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR). Premier was released in the United States in 1988. It was the first commercial heated tobacco product. However, it was difficult to use and tasted unpleasant; as a result, it was unpopular with consumers. A commercial failure, the brand was a significant financial loss for RJR and was quickly taken off the market.

A vaporizer or vaporiser, colloquially known as a vape, is a device used to vaporize substances for inhalation. Plant substances can be used, commonly cannabis, tobacco, or other herbs or blends of essential oil. However, they can also be filled with a combination propylene glycol, glycerin, and drugs such as nicotine or tetrahydrocannabinol as a liquid solution.

Nicotine marketing is the marketing of nicotine-containing products or use. Traditionally, the tobacco industry markets cigarette smoking, but it is increasingly marketing other products, such as electronic cigarettes and heat-not-burn products. Products are marketed through social media, stealth marketing, mass media, and sponsorship. Expenditures on nicotine marketing are in the tens of billions a year; in the US alone, spending was over US$1 million per hour in 2016; in 2003, per-capita marketing spending was $290 per adult smoker, or $45 per inhabitant. Nicotine marketing is increasingly regulated; some forms of nicotine advertising are banned in many countries. The World Health Organization recommends a complete tobacco advertising ban.

Smokeless tobacco is a tobacco product that is used by means other than smoking. Their use involves chewing, sniffing, or placing the product between gum and the cheek or lip. Smokeless tobacco products are produced in various forms, such as chewing tobacco, snuff, snus, and dissolvable tobacco products. Smokeless tobacco products typically contain over 3000 constituents. All smokeless tobacco products contain nicotine and are therefore highly addictive. Quitting smokeless tobacco use is as challenging as smoking cessation.

An electronic cigarette is a electronic device that simulates tobacco smoking. E-cigarettes are handheld battery-powered vaporizers. Using an e-cigarette is called "vaping". Instead of cigarette smoke, the user inhales an aerosol, commonly called vapor. They typically have a heating element that atomizes a liquid solution called e-liquid. They are activated by taking a puff or pressing a button. Some look like traditional cigarettes. Most versions are reusable.

A flavored tobacco product is a tobacco product with added flavorings. Flavored tobacco products include types of cigarettes, cigarillos and cigars, hookah and hookah tobacco, and various types of smokeless tobacco. Flavored tobacco products are especially popular with youth and have therefore become targets of regulation in several countries.

→Regulation of electronic cigarettes varies across countries and states, ranging from no regulation to banning them entirely. For instance, e-cigarettes were illegal in Japan, which forced the market to use heat-not-burn tobacco products for cigarette alternatives. Others have introduced strict restrictions and some have licensed devices as medicines such as in the UK. However, as of February 2018, there is no e-cigarette device that has been given a medical license that is commercially sold or available by prescription in the UK. As of 2015, around two thirds of major nations have regulated e-cigarettes in some way. Because of the potential relationship with tobacco laws and medical drug policies, e-cigarette legislation is being debated in many countries. The companies that make e-cigarettes have been pushing for laws that support their interests. In 2016 the US Department of Transportation banned the use of e-cigarettes on commercial flights. This regulation applies to all flights to and from the US. In 2018, the Royal College of Physicians asked that a balance is found in regulations over e-cigarettes that ensure product safety while encouraging smokers to use them instead of tobacco, as well as keep an eye on any effects contrary to the control agencies for tobacco. A recent study shows electronic device company "JUUL" contains carcinogens and other harmful ingredients inside their e-juice cartridges.

blu is an electronic cigarette brand owned by tobacco giant Imperial Brands. The brand sells its products in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Italy and Russian Federation.

The safetyofelectronic cigarettes is uncertain. There is little data about their safety, and considerable variation among e-cigarettes and in their liquid ingredients and thus the contents of the aerosol delivered to the user. Reviews on the safety of e-cigarettes have reached significantly different conclusions. A 2014 World Health Organization (WHO) report cautioned about potential risks of using e-cigarettes. Regulated US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) products such as nicotine inhalers may be safer than e-cigarettes, but e-cigarettes are generally seen as safer than combusted tobacco products such as cigarettes and cigars. The risk of early death is anticipated to be similar to that of smokeless tobacco. Since vapor does not contain tobacco and does not involve combustion, users may avoid several harmful constituents usually found in tobacco smoke, such as ash, tar, and carbon monoxide. In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Physicians states that "The hazard to health arising from long-term vapour inhalation from the e-cigarettes available today is unlikely to exceed 5% of the harm from smoking tobacco." Their report, Nicotine without Smoke, states that "in the interests of public health it is important to promote the use of e-cigarettes, NRT and other non-tobacco nicotine products as widely as possible as a substitute for smoking in the UK."

An electronic cigarette is a handheld battery-powered vaporizer that simulates smoking, but without tobacco combustion. E-cigarette components include a mouthpiece, a cartridge, a heating element/atomizer, a microprocessor, a battery, and some of them have an LED light on the end. An exception to this are mechanical e-cigarettes (mods) which contain no electronics and the circuit is closed by using a mechanical action switch. An atomizer consists of a small heating element, or coil, that vaporizes e-liquid and a wicking material that draws liquid onto the coil. When the user inhales a flow sensor activates the heating element that atomizes the liquid solution; most devices are manually activated by a push-button. The e-liquid reaches a temperature of roughly 100–250 °C (212–482 °F) within a chamber to create an aerosolized vapor. The user inhales an aerosol, which is commonly but inaccurately called vapor, rather than cigarette smoke. Vaping is different than smoking, but there are some similarities, including the hand-to-mouth action of smoking and a vapor that looks like cigarette smoke. The aerosol provides a flavor and feel similar to tobacco smoking. A traditional cigarette is smooth and light but an e-cigarette is rigid, cold and slightly heavier. There is a learning curve to use e-cigarettes properly. E-cigarettes are cigarette-shaped, and there are many other variations. E-cigarettes that resemble pens or USB memory sticks are also sold that may be used unobtrusively.

The chemical composition of the electronic cigarette aerosol varies across and within manufacturers. Limited data exists regarding their chemistry. The aerosol of e-cigarettes is generated when the e-liquid comes in contact with a coil heated to a temperature of roughly 100–250 °C within a chamber, which is thought to cause pyrolysis of the e-liquid and could also lead to decomposition of other liquid ingredients. The aerosol (mist) produced by an e-cigarette is commonly but inaccurately called vapor. E-cigarettes simulates the action of smoking, but without tobacco combustion. The e-cigarette vapor looks like cigarette smoke to some extent. E-cigarettes do not produce vapor between puffs. The e-cigarette vapor usually contains propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, flavors, aroma transporters, and other substances. The levels of nicotine, tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs), aldehydes, metals, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), flavors, and tobacco alkaloids in e-cigarette vapors vary greatly. The yield of chemicals found in the e-cigarette vapor varies depending on, several factors, including the e-liquid contents, puffing rate, and the battery voltage.

A vape shop is a retail outlet specializing in the selling of electronic cigarette products. There are also online vape shops. A vape shop offers a range of e-cigarette products. The majority of vape shops do not sell e-cigarette products that are from "Big Tobacco" companies. In 2013, online search engine searches on vape shops surpassed searches on e-cigarettes. Around a third of all sales of e-cigarette products take place in vape shops. Big Tobacco believes the independent e-cigarette market is a threat to their interests.

There are various types of heat-not-burn products. Heat-not-burn tobacco products heat up tobacco using a battery-powered heating system. As it starts to heat the tobacco, it generates an aerosol that contains nicotine and other chemicals, that is inhaled. They also generate smoke. Gases, liquid and solid particles, and tar are found in the emissions. They contain nicotine, which is the reason these products are highly addictive. They also contain additives not found in tobacco, and are frequently flavored. It heats tobacco leaves at a lower temperature than traditional cigarettes, which is about 250–350 °C. These products provide some of the behavioral aspects of smoking. The heat source may be embedded; external; or a heated sealed chamber; to deliver nicotine using tobacco leaf. Some use product-specific customized cigarettes. Without using an electrically controlled heating system, there is a device that uses a carbon heat source that, once lit, passes heat to a processed tobacco plug. There are devices that use cannabis. They are not electronic cigarettes. They can overlap with e-cigarettes such as a combination of an e-cigarette and a heat-not-burn tobacco product, for the use of tobacco or e-liquid.

The short-term and long-term adverse effects from electronic cigarette use remain unclear. The long-term effects of e-cigarette use are unknown. The risk from serious adverse events, including death, was reported in 2016 to be low. 64 deaths associated with the use of vaping products have been confirmed in the US, as of February 4, 2020. The long-term health consequences from vaping is probably to be slighter greater than nicotine replacement products. They may produce less adverse effects compared to tobacco products. They may cause long-term and short-term adverse effects, including airway resistance, irritation of the airways, eyes redness, and dry throat. Serious adverse events related to e-cigarettes were hypotension, seizure, chest pain, rapid heartbeat, disorientation, and congestive heart failure but it was unclear the degree to which they were the result of e-cigarettes. Less serious adverse effects include abdominal pain, dizziness, headache, blurry vision, throat and mouth irritation, vomiting, nausea, and coughing. Short-term adverse effects reported most often were mouth and throat irritation, dry cough, and nausea.

Since the introduction of electronic cigarettes to the market in 2003, their global usage has risen exponentially. In 2011, there were approximately seven million adult e-cigarette users globally to 41 million of them in 2018. Awareness and use of e-cigarettes greatly increased over the few years leading up to 2014, particularly among young people and women in some parts of the world. Since their introduction vaping has increased in the majority of high-income countries. E-cigarette use in the US and Europe is higher than in other countries, except for China which has the greatest number of e-cigarette users. Growth in the UK as of January 2018 had reportedly slowed since 2013. The growing frequency of e-cigarette use may be due to heavy promotion in youth-driven media channels, their low cost, and the misbelief that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional cigarettes, according to a 2016 review.. E-cigarette use may also be increasing due to the consensus among several scientific organizations that e-cigarettes are safer compared to combustible tobacco products. E-cigarette use also appears to be increasing at the same time as a rapid decrease in cigarette use in many countries, suggesting that e-cigarettes may be displacing traditional cigarettes.

Exposure to nicotine-containing electronic cigarettes during adolescence can impair the developing human brain. E-cigarette use is recognized as a substantial threat to adolescent behavioral health. The use of tobacco products, no matter what type, is almost always started and established during adolescence when the developing brain is most vulnerable to nicotine addiction. Young people's brains build synapses faster than adult brains. Because addiction is a form of learning, adolescents can get addicted more easily than adults. The nicotine in e-cigarettes can also prime the adolescent brain for addiction to other drugs such as cocaine. Exposure to nicotine and its great risk of developing an addiction, are areas of significant concern.

Electronic cigarettes are marketed to smoking and non-smoking men, women, and children as being safer than traditional cigarettes. E-cigarette businesses have considerably accelerated their marketing spending. All of the large tobacco businesses are engaging in the marketing of e-cigarettes. For the majority of the large tobacco businesses these products are quickly becoming a substantial part of the total advertising spending. E-cigarette businesses have a vested interest in maximizing the number of long-term product users. The entrance of traditional transnational tobacco businesses in the marketing of such products is a serious threat to restricting tobacco use. E-cigarette businesses have been using intensive marketing strategies like those used to publicize traditional cigarettes in the 1950s and 1960s. While advertising of tobacco products is banned in most countries, television and radio e-cigarette advertising in several countries may be indirectly encouraging traditional cigarette use.

Nicotine salts are salts consisting of nicotine and an acid. They are found naturally in tobacco leaves.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Pieper, Elke; Mallock, Nadja; Henkler-Stephani, Frank; Luch, Andreas (2018). "Tabakerhitzer als neues Produkt der Tabakindustrie: Gesundheitliche Risiken" ["Heat not burn" tobacco devices as new tobacco industry products: health risks]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (in German). 61 (11): 1422–1428. doi: 10.1007/s00103-018-2823-y . ISSN 1436-9990. PMID 30284624.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dautzenberg, B.; Dautzenberg, M.-D. (2018). "Le tabac chauffé : revue systématique de la littérature" [Systematic analysis of the scientific literature on heated tobacco]. Revue des Maladies Respiratoires (in French). 36 (1): 82–103. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2018.10.010 . ISSN 0761-8425. PMID 30429092.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kaur, Gurjot; Muthumalage, Thivanka; Rahman, Irfan (2018). "Mechanisms of toxicity and biomarkers of flavoring and flavor enhancing chemicals in emerging tobacco and non-tobacco products". Toxicology Letters. 288: 143–155. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.02.025. ISSN 0378-4274. PMC 6549714 . PMID 29481849.

- ↑ Jenssen, Brian P.; Walley, Susan C.; McGrath-Morrow, Sharon A. (2017). "Heat-not-Burn Tobacco Products: Tobacco Industry Claims No Substitute for Science". Pediatrics. 141 (1): e20172383. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2383 . ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 29233936.

- ↑ Ziedonis, Douglas; Das, Smita; Larkin, Celine (2017). "Tobacco use disorder and treatment: New challenges and opportunities". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 19 (3): 271–80. PMC 5741110 . PMID 29302224.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kaunelienė, Violeta; Meišutovič-Akhtarieva, Marija; Martuzevičius, Dainius (2018). "A review of the impacts of tobacco heating system on indoor air quality versus conventional pollution sources". Chemosphere. 206: 568–578. Bibcode:2018Chmsp.206..568K. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.05.039 . ISSN 0045-6535. PMID 29778082.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 McNeill 2018, p. 210.

- 1 2 McNeill 2018, p. 219.

- 1 2 Elias, Jesse; Dutra, Lauren M; St. Helen, Gideon; Ling, Pamela M (2018). "Revolution or redux? Assessing IQOS through a precursor product". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): s102–s110. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054327. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6238084 . PMID 30305324.

- 1 2 Staal, Yvonne CM; van de Nobelen, Suzanne; Havermans, Anne; Talhout, Reinskje (2018). "New Tobacco and Tobacco-Related Products: Early Detection of Product Development, Marketing Strategies, and Consumer Interest". JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 4 (2): e55. doi:10.2196/publichealth.7359. ISSN 2369-2960. PMC 5996176 . PMID 29807884.

- ↑ Shi, Yuyan; Caputi, Theodore L.; Leas, Eric; Dredze, Mark; Cohen, Joanna E.; Ayers, John W. (2017). "They're heating up: Internet search query trends reveal significant public interest in heat-not-burn tobacco products". PLOS One. 12 (10): e0185735. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1285735C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185735. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5636077 . PMID 29020019.

- ↑ Bialous, Stella A; Glantz, Stanton A (2018). "Heated tobacco products: another tobacco industry global strategy to slow progress in tobacco control". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): s111–s117. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054340. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6202178 . PMID 30209207.

- 1 2 "Heated tobacco products (HTPs) information sheet". World Health Organization. May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 McNeill 2018, p. 216.

- 1 2 Górski, Paweł (2019). "E-cigarettes or heat-not-burn tobacco products – advantages or disadvantages for the lungs of smokers". Advances in Respiratory Medicine. 87 (2): 123–134. doi: 10.5603/ARM.2019.0020 . ISSN 2543-6031. PMID 31038725.

- ↑ Li, Xiangyu; Luo, Yanbo; Jiang, Xingyi; Zhang, Hongfei; Zhu, Fengpeng; Hu, Shaodong; Hou, Hongwei; Hu, Qingyuan; Pang, Yongqiang (2019). "Chemical Analysis and Simulated Pyrolysis of Tobacco Heating System 2.2 Compared to Conventional Cigarettes". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 21 (1): 111–118. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty005. ISSN 1462-2203. PMID 29319815.