Aachen Cathedral is a Catholic church in Aachen, Germany and the cathedral of the Diocese of Aachen.

The Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram is a 9th-century illuminated Gospel Book. It takes its name from Saint Emmeram's Abbey, where it was for most of its history and is lavishly illuminated. The cover of the codex is decorated with gems and relief figures in gold, and can be precisely dated to 870, and is an important example of Carolingian art, as well as one of very few surviving treasure bindings of this date.

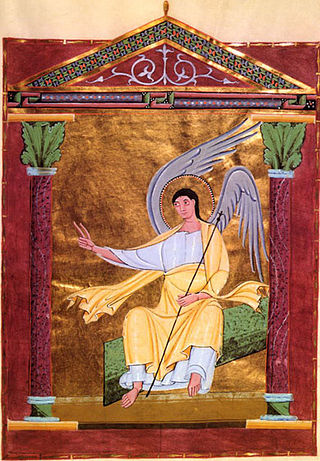

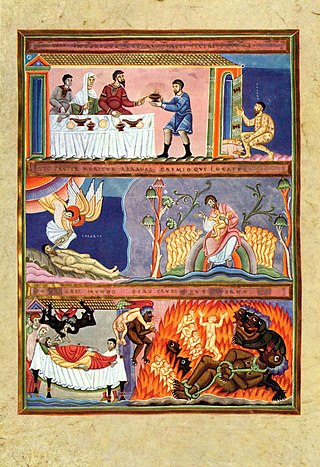

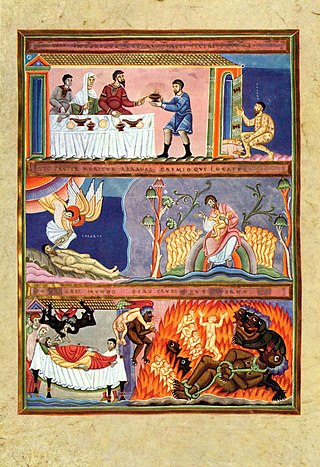

The Pericopes of Henry II is a luxurious medieval illuminated manuscript made for Henry II, the last Ottonian Holy Roman Emperor, made c. 1002–1012 AD. The manuscript, which is lavishly illuminated, is a product of the Liuthar circle of illuminators, who were working in the Benedictine Abbey of Reichenau, which housed a scriptorium and artists' workshop that has a claim to having been the largest and artistically most influential in Europe during the late 10th and early 11th centuries. An unrivalled series of liturgical manuscripts was produced at Reichenau under the highest patronage of Ottonian society.

Pre-Romanesque art and architecture is the period in European art from either, the emergence of the Merovingian kingdom in about 500 AD or from the Carolingian Renaissance in the late 8th century, to the beginning of the 11th century Romanesque period. The term is generally used in English only for architecture and monumental sculpture, but here all the arts of the period are briefly described.

Carolingian art comes from the Frankish Empire in the period of roughly 120 years from about 780 to 900—during the reign of Charlemagne and his immediate heirs—popularly known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The art was produced by and for the court circle and a group of important monasteries under Imperial patronage; survivals from outside this charmed circle show a considerable drop in quality of workmanship and sophistication of design. The art was produced in several centres in what are now France, Germany, Austria, northern Italy and the Low Countries, and received considerable influence, via continental mission centres, from the Insular art of the British Isles, as well as a number of Byzantine artists who appear to have been resident in Carolingian centres.

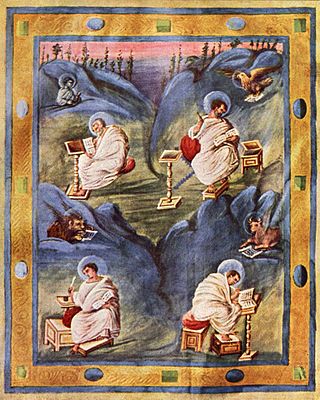

Ottonian art is a style in pre-romanesque German art, covering also some works from the Low Countries, northern Italy and eastern France. It was named by the art historian Hubert Janitschek after the Ottonian dynasty which ruled Germany and Northern Italy between 919 and 1024 under the kings Henry I, Otto I, Otto II, Otto III and Henry II. With Ottonian architecture, it is a key component of the Ottonian Renaissance. However, the style neither began nor ended to neatly coincide with the rule of the dynasty. It emerged some decades into their rule and persisted past the Ottonian emperors into the reigns of the early Salian dynasty, which lacks an artistic "style label" of its own. In the traditional scheme of art history, Ottonian art follows Carolingian art and precedes Romanesque art, though the transitions at both ends of the period are gradual rather than sudden. Like the former and unlike the latter, it was very largely a style restricted to a few of the small cities of the period, and important monasteries, as well as the court circles of the emperor and his leading vassals.

A crux gemmata is a form of cross typical of Early Christian and Early Medieval art, where the cross, or at least its front side, is principally decorated with jewels. In an actual cross, rather than a painted image of one, the reverse side often has engraved images of the Crucifixion of Jesus or other subjects.

The Gero Cross or Gero Crucifix, of around 965–970, is the oldest large sculpture of the crucified Christ north of the Alps, and has always been displayed in Cologne Cathedral in Germany. It was commissioned by Gero, Archbishop of Cologne, who died in 976, thus providing a terminus ante quem for the work. It is carved in oak, and painted and partially gilded – both have been renewed. The halo and cross-pieces are original, but the Baroque surround was added in 1683. The figure is 187 cm high, and the span of its arms is 165 cm. It is the earliest known Western depiction of Christ on the cross while dead; earlier depictions had Christ appearing alive.

Imperial cathedral is the designation for a cathedral linked to the Imperial rule of the Holy Roman Empire.

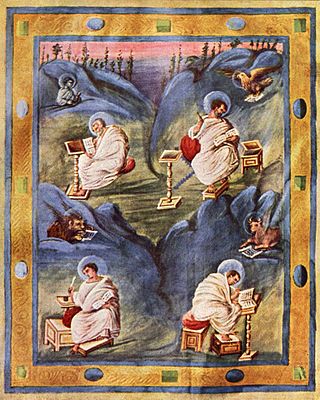

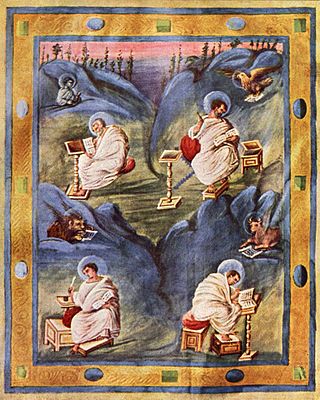

The Gospels of Otto III is considered a superb example of Ottonian art because of the scope, planning, and execution of the work. The book has 276 parchment pages and has twelve canon tables, a double page portrait of Otto III, portraits of the four evangelists, and 29 full page miniatures illustrating scenes from the New Testament. The cover is the original, with a tenth-century carved Byzantine ivory inlay representing the Dormition of the Virgin. Produced at the monastery at Reichenau Abbey in about 1000 CE, the manuscript is an example of the highest quality work that was produced over 150 years at the monastery.

The Codex Aureus of Echternach is an illuminated Gospel Book, created in the approximate period 1030–1050, with a re-used front cover from around the 980s. It is now in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg.

The Hand of God, or Manus Dei in Latin, also known as Dextera domini/dei, is a motif in Jewish and Christian art, especially of the Late Antique and Early Medieval periods, when depiction of Yahweh or God the Father as a full human figure was considered unacceptable. The hand, sometimes including a portion of an arm, or ending about the wrist, is used to indicate the intervention in or approval of affairs on Earth by God, and sometimes as a subject in itself. It is an artistic metaphor that is generally not intended to indicate that a hand was physically present or seen at any subject depicted. The Hand is seen appearing from above in a fairly restricted number of narrative contexts, often in a blessing gesture, but sometimes performing an action. In later Christian works it tends to be replaced by a fully realized figure of God the Father, whose depiction had become acceptable in Western Christianity, although not in Eastern Orthodox or Jewish art. Though the hand of God has traditionally been understood as a symbol for God's intervention or approval of human affairs, it is also possible that the hand of God reflects the anthropomorphic conceptions of the deity that may have persisted in late antiquity.

Christ treading on the beasts is a subject found in Late Antique and Early Medieval art, though it is never common. It is a variant of the "Christ in Triumph" subject of the resurrected Christ, and shows a standing Christ with his feet on animals, often holding a cross-staff which may have a spear-head at the bottom of its shaft, or a staff or spear with a cross-motif on a pennon. Some art historians argue that the subject exists in an even rarer pacific form as "Christ recognised by the beasts".

The Lothair Crystal is an engraved gem from Lotharingia in northwest Europe, showing scenes of the biblical story of Susanna, dating from 855–869. The Lothair Crystal is an object in the collection of the British Museum.

The Lindau Gospels is an illuminated manuscript in the Morgan Library in New York, which is important for its illuminated text, but still more so for its treasure binding, or metalwork covers, which are of different periods. The oldest element of the book is what is now the back cover, which was probably produced in the later 8th century in modern Austria, but in the context of missionary settlements from Britain or Ireland, as the style is that of the Insular art of the British Isles. The upper cover is late Carolingian work of about 880, and the text of the gospel book itself was written and decorated at the Abbey of Saint Gall around the same time, or slightly later.

The Liuthar Gospels are a work of Ottonian illumination which are counted among the masterpieces of the period known as the Ottonian Renaissance. The manuscript, named after a monk called Liuthar, was probably created around the year 1000 at the order of Otto III at the Abbey of Reichenau and lends its name to the Liuthar Group of Reichenau illuminated manuscripts. The backgrounds of all the images are illuminated in gold leaf, a seminal innovation in western illumination.

The Aachen Cathedral Treasury is a museum of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Aachen under the control of the cathedral chapter, which houses one of the most important collections of medieval church artworks in Europe. In 1978, the Aachen Cathedral Treasury, along with Aachen Cathedral, was the first monument on German soil to be entered in the List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The treasury contains works from Late Antique, Carolingian, Ottonian, Staufen, and Gothic times. The exhibits are displayed in premises connected to the cathedral cloisters.

The Aachen Gospels are a Carolingian illuminated manuscript which was created at the beginning of the ninth century by a member of the Ada School. The Evangeliary belongs to a manuscript group which is referred to as the Ada Group or Group of the Vienna Coronation Gospels. It is part of the church treasury of Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel, now Aachen Cathedral, and is today kept in the Aachen Cathedral Treasury. The Treasury Gospels and the more recent Ottonian Liuthar Gospels are the two most significant medieval manuscripts on display there.

The Cross of Otto and Mathilde, Otto-Mathilda Cross, or First Cross of Mathilde is a medieval crux gemmata processional cross in the Essen Cathedral Treasury. It was created in the late tenth century and was used on high holidays until recently. It is named after the two persons who appear on the enamel plaque below Christ: Otto I, Duke of Swabia and Bavaria and his sister, Mathilde, the abbess of the Essen Abbey. They were grandchildren of the emperor Otto I and favourites of their uncle, Otto II. The cross is one of the items which demonstrate the very close relationship between the Liudolfing royal house and Essen Abbey. Mathilde became Abbess of Essen in 973 and her brother died in 982, so the cross is assumed to have been made between those dates, or a year or two later if it had a memorial function for Otto. Like other objects in Essen made under the patronage of Mathilde, the location of the goldsmith's workshop is uncertain, but as well as Essen itself, Cologne has often been suggested, and the enamel plaque may have been made separately in Trier.

The Magdeburg Ivories are a set of 16 surviving ivory panels illustrating episodes of Christ's life. They were commissioned by Emperor Otto I, probably to mark the dedication of Magdeburg Cathedral, and the raising of the Magdeburg see to an archbishopric in 968. The panels were initially part of an unknown object in the cathedral that has been variously conjectured to be an antependium or altar front, a throne, door, pulpit, or an ambon; traditionally this conjectural object, and therefore the ivories as a group, has been called the Magdeburg Antependium. This object is believed to have been dismantled or destroyed in the 1000s, perhaps after a fire in 1049.