The 1991 Bangladesh cyclone was among the deadliest tropical cyclones on record. Forming out of a large area of convection over the Bay of Bengal on April 24, the tropical cyclone initially developed gradually while meandering over the southern Bay of Bengal. On April 28, the storm began to accelerate northeastwards under the influence of the southwesterlies, and rapidly intensified to super cyclonic storm strength near the coast of Bangladesh on April 29. After making landfall in the Chittagong district of southeastern Bangladesh with winds of around 250 km/h (155 mph), the cyclone rapidly weakened as it moved through northeastern India, degenerating into a remnant low over the Yunnan province in western China.

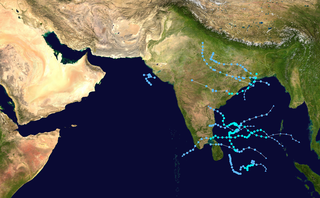

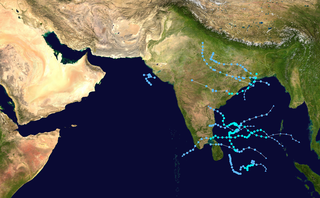

The 2005 North Indian Ocean cyclone season caused much devastation and many deaths in Southern India despite the storms’ weakness. The basin covers the Indian Ocean north of the equator as well as inland areas, sub-divided by the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. Although the season began early with two systems in January, the bulk of activity was confined from September to December. The official India Meteorological Department tracked 12 depressions in the basin, and the unofficial Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) monitored two additional storms. Three systems intensified into a cyclonic storm, which have sustained winds of at least 63 km/h (39 mph), at which point the IMD named them.

The 2006 North Indian Ocean cyclone season had no bounds, but cyclones tend to form between April and December, with peaks in May and November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean.

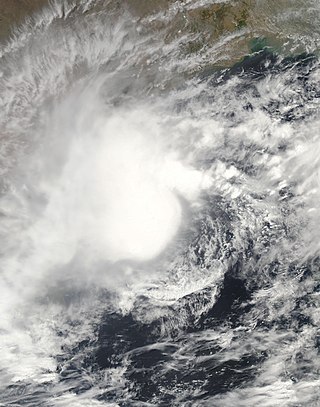

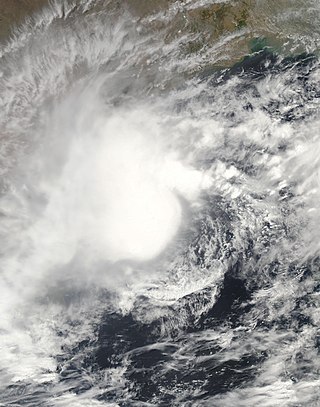

Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Mala was the strongest tropical cyclone of the 2006 North Indian Ocean cyclone season. In mid-April 2006, an area of disturbed weather formed over the southern Bay of Bengal and nearby Andaman Sea. Over a period of several days, the system became increasingly organized and was classified as a depression on April 24. Situated within a region of weak steering currents, the storm slowly intensified as it drifted in a general northward direction. It attained gale-force winds and was named Mala the next day. Conditions for strengthening improved markedly on April 27 and Mala subsequently underwent rapid intensification which culminated in the cyclone attaining its peak. Early on April 28, the cyclone had estimated winds of 185 km/h (115 mph). The Joint Typhoon Warning Center considered Mala to have been slightly stronger, classifying it as a Category 4-equivalent cyclone. Steady weakening ensued thereafter and the storm made landfall in Myanmar's Rakhine State on April 29. Rapid dissipation took place once onshore and Mala was last noted early the next morning.

The 2008 North Indian cyclone season was one of the most disastrous tropical cyclone seasons in modern history, causing more than 140,000 fatalities and over US$15 billion in damage. At the time, it was the costliest season in the North Indian Ocean, until it was surpassed by 2020. The season has no official bounds but cyclones tend to form between April and December. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean. There are two main seas in the North Indian Ocean—the Bay of Bengal, which is east of India, and the Arabian Sea, which is west of India. The official Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre in this basin is the India Meteorological Department (IMD), however the Joint Typhoon Warning Center releases unofficial advisories for military interests. An average of four to six storms form in the North Indian Ocean every season. Cyclones occurring between the meridians 45°E and 100°E are included in the season by the IMD.

The 2004 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was the first in which tropical cyclones were officially named in the basin. Cyclone Onil, which struck India and Pakistan, was named in late September. The final storm, Cyclone Agni, was also named, and crossed into the southern hemisphere shortly before dissipation. This storm became notable during its origins and became one of the storms closest to the equator. The season was fairly active, with ten depressions forming from May to November. The India Meteorological Department designated four of these as cyclonic storms, which have maximum sustained winds of at least 65 km/h (40 mph) averaged over three minutes. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center also issued warnings for five of the storms on an unofficial basis.

The 2003 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was the last season that tropical cyclones were not publicly labeled by India Meteorological Department (IMD). Also was mostly focused in the Bay of Bengal, where six of the seven depressions developed. The remaining system was a tropical cyclone that developed in the Arabian Sea in November, which was also the only system that did not affect land. There were three cyclonic storms, which was below the average of 4–6. Only one storm formed before the start of the monsoon season in June, although it was also the most notable. On May 10, a depression formed in the central Bay of Bengal, and within a few days became a very severe cyclonic storm. After it stalled, it drew moisture from the southwest to produce severe flooding across Sri Lanka, killing 254 people and becoming the worst floods there since 1947. Damage on the island totaled $135 million (2003 USD). The storm eventually made landfall in Myanmar on May 19. It is possible that the storm contributed to a deadly heat wave in India due to shifting air currents.

The 2000 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was fairly quiet compared to the year before, 1999 North Indian Ocean cyclone season, with all of the activity originating in the Bay of Bengal. The basin comprises the Indian Ocean north of the equator, with warnings issued by the India Meteorological Department (IMD) in New Delhi. There were six depressions throughout the year, of which five intensified into cyclonic storms – tropical cyclones with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) sustained over 3 minutes. Two of the storms strengthened into a Very Severe Cyclonic Storm, which has winds of at least 120 km/h (75 mph), equivalent to a minimal hurricane. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) also tracked storms in the basin on an unofficial basis, estimating winds sustained over 1 minute.

The 1995 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was below-average and was primarily confined to the autumn months, with the exception of three short-lived deep depressions in May. There were eight depressions in the basin, which is Indian Ocean north of the equator. The basin is subdivided between the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea on the east and west coasts of India, respectively. Storms were tracked by the India Meteorological Department (IMD), which is the basin's Regional Specialized Meteorological Center, as well as the American-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) on an unofficial basis.

Cyclonic Storm Bijli, was the first tropical cyclone to form during the 2009 North Indian Ocean cyclone season. Bijli formed from an area of Low Pressure on April 14. Later that evening, RSMC New Delhi upgraded the low-pressure area to a Depression and designated it as BOB 01. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) then issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert for the system and soon after designated it as Tropical Depression 01B. On the evening of April 15, both RSMC New Delhi and the JTWC reported that the system had intensified into a tropical storm, with the former naming it Bilji. Soon after, Bilji reached its peak intensity as it approached the coast of Bangladesh. However, on the morning of April 17, Bijli weakened to a deep depression due to land interaction, before making landfall just south of Chittagong. The remnants of Bilji continued to weaken as they tracked across northern Myanmar, before RSMC New Delhi issued their last advisory on April 18. The word Bijli refers to lightning in Hindi.

Severe Cyclonic Storm Aila was the second named tropical cyclone of the 2009 North Indian Ocean cyclone season. Warned by both the Regional Specialized Meteorological Center (RMSC) and Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC), Aila formed over a disturbance over the Bay of Bengal on May 23, 2009 and started to intensify and organize reaching sustained wind speeds of 110 kmh (70 mph). It was the worst natural disaster to affect Bangladesh since Cyclone Sidr in November 2007. A relatively strong tropical cyclone, it caused extensive damage in India and Bangladesh.

At least 29 tropical cyclones have affected Myanmar, a country adjacent to the Bay of Bengal in mainland Southeast Asia. Myanmar has witnessed some of the deadliest storms in the Bay of Bengal, including Cyclone Nargis in May 2008, which struck the low-lying Irrawaddy Delta near Yangon. Its winds and storm surge killed an estimated 140,000 people and left nearly $10 billion in damage. The country's worst natural disaster in the 20th century was a cyclone in 1968, which killed more than 1,000 people when it hit Rakhine State in northwestern Myanmar. One of the most powerful storms to ever hit the country was Cyclone Mocha, which it moved ashore northwestern Myanmar in May 2023, killing at least 413 people.

Cyclonic Storm Viyaru, operationally known as Cyclonic Storm Mahasen, was a relatively weak tropical cyclone that caused loss of life across six countries in Southern and Southeastern Asia. Originating from an area of low pressure over the southern Bay of Bengal in early May 2013, Viyaru slowly consolidated into a depression on May 10. The depression gained forward momentum and attained gale-force winds on May 11 and was designated as Cyclonic Storm Viyaru, the first named storm of the season. Owing to adverse atmospheric conditions, the depression struggled to maintain organized convection as it moved closer to eastern India. On May 14, the exposed circulation of Viyaru turned northeastward. The following day, conditions again allowed for the storm to intensify. Early on May 16, the cyclone attained its peak intensity with winds of 85 km/h (55 mph) and a barometric pressure of 990 mbar. Shortly thereafter Viyaru made landfall near Chittagong, Bangladesh. On May 17, it moved over the eastern Indian state of Nagaland.

In May 2003, a tropical cyclone officially called Very Severe Cyclonic Storm BOB 01 produced the worst flooding in Sri Lanka in 56 years. The first storm of the 2003 North Indian Ocean cyclone season, it developed over the Bay of Bengal on May 10. Favorable environmental conditions allowed the system to intensify steadily while moving northwestward. The storm reached peak maximum sustained winds of 140 km/h (85 mph) on May 13, making it a very severe cyclonic storm according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), which is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the basin. The cyclone drifted north over the central Bay of Bengal, gradually weakening due to heightened wind shear. Turning eastward, the storm deteriorated to a deep depression on May 16 before it curved northeastward and re-intensified into a cyclonic storm. It came ashore in western Myanmar and dissipated over land the following day.

The 2004 Myanmar cyclone was considered the worst to strike the country since 1968. The second tropical cyclone of the 2004 North Indian Ocean cyclone season, it formed as a depression on May 16 in the central Bay of Bengal. With low wind shear and a surge in the monsoon trough, the storm intensified while meandering over open waters. The storm eventually began a steady northeastward motion due to a ridge to the north over India. While approaching land, an eye developed in the center of the storm, indicative of a strong cyclone. On May 19, the cyclone made landfall along northwestern Myanmar near Sittwe, with maximum sustained winds estimated at 165 km/h (105 mph) by the India Meteorological Department. The storm rapidly weakened over land, although its remnants spread rainfall into northern Thailand and Yunnan province in China.

The 2015 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was an event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation. The North Indian Ocean cyclone season has no official bounds, but cyclones tend to form between months of April and December, with the peak from May to November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean.

The 2017 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was a below average yet deadly season in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation. This season produced only three named storms, of which one only intensified into a very severe cyclonic storm. The North Indian Ocean cyclone season has no official bounds but cyclones tend to form between April and December with the two peaks in May and November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean. The season began with the formation Cyclone Maarutha on April 15 and ended with the dissipation of a deep depression on December 9.

Severe Cyclonic Storm Mora was a moderate but deadly tropical cyclone that caused widespread devastation and severe flooding in Sri Lanka, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bangladesh, Myanmar and Northeast India in May 2017. The second named storm of the 2017 annual cyclone season, Mora developed from an area of low pressure over the southeastern Bay of Bengal on May 28. Mora reached peak strength with maximum sustained winds of 110 km/h (70 mph). The cyclone made landfall near Chittagong on the morning of May 30 and steadily weakened, dissipating early in the morning on May 31. Across its path, Mora dropped a large amount of rain, including 225mm of rainfall in Chittagong and northeast India. The storm is estimated to have caused damages nearing US$300 million.

The 2018 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was one of the most active North Indian Ocean cyclone seasons since 1992, with the formation of fourteen depressions and seven cyclones. The North Indian Ocean cyclone season has no official bounds, but cyclones tend to form between April and December, with the two peaks in May and November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean.

Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Mocha was a powerful and deadly tropical cyclone in the North Indian Ocean which affected Myanmar and parts of Bangladesh in May 2023. The second depression and the first cyclonic storm of the 2023 North Indian Ocean cyclone season, Mocha originated from a low-pressure area that was first noted by the India Meteorological Department (IMD) on 8 May. After consolidating into a depression, the storm tracked slowly north-northwestward over the Bay of Bengal, and reached extremely severe cyclonic storm intensity. After undergoing an eyewall replacement cycle, Mocha rapidly strengthened, peaking at Category 5-equivalent intensity on 14 May with winds of 280 km/h (175 mph), tying with Cyclone Fani as the strongest storm on record in the North Indian Ocean in terms of 1-minute sustained winds. Mocha slightly weakened before making landfall, and its conditions quickly became unfavorable. Mocha rapidly weakened once inland and dissipated shortly thereafter.