The Himalayas, or Himalaya, is a mountain range separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest which lies on the border of China and Nepal. Over 100 peaks exceeding 7,200 m (23,600 ft) in elevation lie in the Himalayas. By contrast, the highest peak outside Asia is 6,961 m (22,838 ft) tall.

The Kingdom of Bhutan is a sovereign nation, located towards the eastern extreme of the Himalayas mountain range. It is fairly evenly sandwiched between the sovereign territory of two nations: first, the People's Republic of China on the north and northwest. There are approximately 477 kilometres of border with that nation's Tibet Autonomous Region. The second nation is the Republic of India on the south, southwest, and east; there are approximately 659 kilometres with the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, West Bengal, and Sikkim, in clockwise order from the kingdom. Bhutan's total borders amount to 1,139 kilometres. The Republic of Nepal to the west, the India to the south, and the Union of Myanmar to the southeast are other close neighbours; the former two are separated by only very small stretches of Indian territory.

Gasa District or Gasa Dzongkhag is one of the 20 dzongkhags (districts) comprising Bhutan. The capital of Gasa District is Gasa Dzong near Gasa. It is located in the far north of the county and spans the Middle and High regions of the Tibetan Himalayas. The dominant language of the district is Dzongkha, which is the national language. Related languages, Layakha and Lunanakha, are spoken by semi-nomadic communities in the north of the district. The People's Republic of China claims the northern part of Gasa District.

Sankosh is a river that rises in northern Bhutan and empties into the Brahmaputra in the state of Assam in India. In Bhutan, it is known as the Puna Tsang Chu below the confluences of several tributaries near the town of Wangdue Phodrang.

Punakha is the administrative centre of Punakha dzongkhag, one of the 20 districts of Bhutan. Punakha was the capital of Bhutan and the seat of government until 1955, when the capital was moved to Thimphu. It is about 72 km away from Thimphu, and it takes about 3 hours by car from the capital. Unlike Thimphu, it is quite warm in winter and hot in summer. It is located at an elevation of 1,200 metres above sea level, and rice is grown as the main crop along the river valleys of two main rivers of Bhutan, the Pho Chu and Mo Chu. Dzongkha is widely spoken in this district.

A glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) is a type of outburst flood caused by the failure of a dam containing a glacial lake. An event similar to a GLOF, where a body of water contained by a glacier melts or overflows the glacier, is called a jökulhlaup. The dam can consist of glacier ice or a terminal moraine. Failure can happen due to erosion, a buildup of water pressure, an avalanche of rock or heavy snow, an earthquake or cryoseism, volcanic eruptions under the ice, or massive displacement of water in a glacial lake when a large portion of an adjacent glacier collapses into it.

The retreat of glaciers since 1850 affects the availability of fresh water for irrigation and domestic use, mountain recreation, animals and plants that depend on glacier-melt, and, in the longer term, the level of the oceans. Deglaciation occurs naturally at the end of ice ages, but glaciologists find the current glacier retreat is accelerated by the measured increase of atmospheric greenhouse gases—an effect of climate change. Mid-latitude mountain ranges such as the Himalayas, Rockies, Alps, Cascades, Southern Alps, and the southern Andes, as well as isolated tropical summits such as Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa, are showing some of the largest proportionate glacial losses. Excluding peripheral glaciers of ice sheets, the total cumulated global glacial losses over the 26 year period from 1993–2018 were likely 5500 gigatons, or 210 gigatons per yr.

A supraglacial lake is any pond of liquid water on the top of a glacier. Although these pools are ephemeral, they may reach kilometers in diameter and be several meters deep. They may last for months or even decades at a time, but can empty in the course of hours.

The Jigme Dorji National Park (JDNP), named after the late Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, is the second-largest National Park of Bhutan. It occupies almost the entire Gasa District, as well as the northern areas of Thimphu District, Paro District, Punakha, and Wangdue Phodrang Districts. It was established in 1974 and stretches over an area of 4316 km², thereby spanning all three climate zones of Bhutan, ranging in elevation from 1400 to over 7000 meters. About 6,500 people in 1,000 households live within the park, from subsistence agriculture and animal husbandry. It is listed as a tentative site in Bhutan's Tentative List for UNESCO inclusion.

The Third Pole, also known as the Hindu Kush-Karakoram-Himalayan system (HKKH), is a mountainous region west and south of the Tibetan Plateau. Part of High-Mountain Asia, it spreads over an area of more than 4.2 million square kilometres across nine countries, i.e. Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Tajikistan. The area is nicknamed "Third Pole" because its mountain glaciers and snowfields store more frozen water than anywhere else in the world except for the Arctic and Antarctic polar caps. With the world's loftiest mountains, comprising all 14 peaks above 8,000 metres (26,000 ft), it is the source of 10 major rivers, and forms a global ecological buffer.

The Punakha Dzong, also known as Pungthang Dewa chhenbi Phodrang, is the administrative centre of Punakha District in Punakha, Bhutan. Constructed by Ngawang Namgyal, 1st Zhabdrung Rinpoche, in 1637–38, it is the second oldest and second-largest dzong in Bhutan and one of its most majestic structures. The dzong houses the sacred relics of the southern Drukpa Lineage of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, including the Rangjung Kharsapani and the sacred remains of Ngawang Namgyal and the tertön Pema Lingpa.

The Sunkoshi, also spelt Sunkosi, is a river of Nepal that is part of the Koshi or Saptkoshi River system in Nepal. Sunkoshi has two source streams, one that arises within Nepal in Choukati, and the other more significant stream that flows in from Nyalam County in the Tibet region of China. The latter is called Bhote Koshi in Nepal and Matsang Tsangpo in Tibet. Due to the significant flows from Bhote Koshi, the Sun Koshi river basin is often regarded as a trans-border river basin.

Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park covers an area of 1,730 square kilometres (670 sq mi) in central Bhutan. It protects a large area of the Black Mountains, a sub−range of the Himalayan Range System.

Wangchuck Centennial National Park in northern Bhutan is the kingdom's largest national park, spanning 4,914 square kilometres (1,897 sq mi) over five districts, occupying significant portions of northern Bumthang, Lhuntse, and Wangdue Phodrang Districts. It borders Tibet to the north and is bound by tributaries of the Wong Chhu (Raidāk) basin to the west. Wangchuck Centennial directly abuts Jigme Dorji National Park, Bumdeling Wildlife Sanctuary, and Phrumsengla National Park in northern Bhutan, and is further connected to Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park in central Bhutan via biological corridors. Thus, most of northern Bhutan is part of these protected areas.

The lakes of Bhutan comprise its glacial lakes and its natural mountain lakes. Bhutanese territory contains some 2,674 high altitude glacial lakes and subsidiary lakes, out of which 25 pose a risk of GLOFs. There are also more than 59 natural non-glacial lakes in Bhutan, covering about 4,250 hectares (16.4 sq mi). Most are located above an altitude of 3,500 metres (11,500 ft), and most have no permanent human settlements nearby, though many are used for grazing yaks and may have scattered temporary settlements.

There are a number of environmental issues in Bhutan. Among Bhutan's most pressing issues are traditional firewood collection, crop and flock protection, and waste disposal, as well as modern concerns such as industrial pollution, wildlife conservation, and climate change that threaten Bhutan's population and biodiversity. Land and water use have also become matters of environmental concern in both rural and urban settings. In addition to these general issues, others such as landfill availability and air and noise pollution are particularly prevalent in relatively urbanized and industrialized areas of Bhutan. In many cases, the least financially and politically empowered find themselves the most affected by environmental issues.

The mountains of Bhutan are some of the most prominent natural geographic features of the kingdom. Located on the southern end of the Eastern Himalaya, Bhutan has one of the most rugged mountain terrains in the world, whose elevations range from 160 metres (520 ft) to more than 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) above sea level, in some cases within distances of less than 100 kilometres (62 mi) of each other. Bhutan's highest peak, at 7,570 metres (24,840 ft) above sea level, is north-central Gangkhar Puensum, close to the border with Tibet; the third highest peak, Jomolhari, overlooking the Chumbi Valley in the west, is 7,314 metres (23,996 ft) above sea level; nineteen other peaks exceed 7,000 metres (23,000 ft). Weather is extreme in the mountains: the high peaks have perpetual snow, and the lesser mountains and hewn gorges have high winds all year round, making them barren brown wind tunnels in summer, and frozen wastelands in winter. The blizzards generated in the north each winter often drift southward into the central highlands.

Climate change in Nepal is a major problem for Nepal as it is one of the most vulnerable countries to the effects of climate change. Globally, Nepal is ranked fourth, in terms of vulnerability to climate change. Floods spread across the foothills of the Himalayas and bring landslides, leaving tens of thousands of houses and vast areas of farmland and roads destroyed. In the 2020 edition of Germanwatch's Climate Risk Index, it was judged to be the ninth hardest-hit nation by climate calamities during the period 1999 to 2018. Nepal is a least developed country, with 28.6 percent of the population living in multidimensional poverty. Analysis of trends from 1971 to 2014 by the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) shows that the average annual maximum temperature has been increasing by 0.056 °C per year. Precipitation extremes are found to be increasing. A national-level survey on the perception-based survey on climate change reported that locals accurately perceived the shifts in temperature but their perceptions of precipitation change did not converge with the instrumental records. Data reveals that more than 80 percent of property loss due to disasters is attributable to climate hazards, particularly water-related events such as floods, landslides and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs).

Thulagi glacier is located in the catchment area of the Marshyangdi River basin in Nepal. A study by KfW, Frankfurt and the BGR, in cooperation with the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology of Nepal have identified it as a potentially dangerous glacier due to possibility of outburst of the lake created by the glacier.

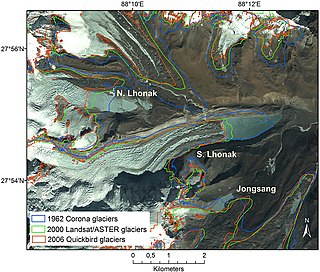

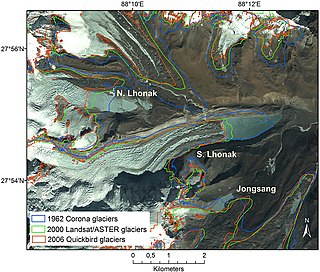

South Lhonak Lake is a glacial-moraine-dammed lake, located in Sikkim's far northwestern region. It is one of the fastest expanding lakes in the Sikkim Himalaya region, and one of the 14 potentially dangerous lakes susceptible to Glacial lake outburst flood (GLOFs).