The Hafsids were a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descent who ruled Ifriqiya from 1229 to 1574.

Moroccan architecture reflects Morocco's diverse geography and long history, marked by successive waves of settlers through both migration and military conquest. This architectural heritage includes ancient Roman sites, historic Islamic architecture, local vernacular architecture, 20th-century French colonial architecture, and modern architecture.

Moorish architecture is a style within Islamic architecture which developed in the western Islamic world, including al-Andalus and what is now Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. Scholarly references on Islamic architecture often refer to this architectural tradition in terms such as architecture of the Islamic West or architecture of the Western Islamic lands. The use of the term "Moorish" comes from the historical Western European designation of the Muslim inhabitants of these regions as "Moors". Some references on Islamic art and architecture consider this term to be outdated or contested.

Al-Zaytuna Mosque, also known as Ez-Zitouna Mosque, and El-Zituna Mosque, is a major mosque at the center of the Medina of Tunis in Tunis, Tunisia. The mosque is the oldest in the city and covers an area of 5,000 square metres with nine entrances. It was founded at the end of the 7th century or in the early 8th century, but its current architectural form dates from a reconstruction in the 9th century, including many antique columns reused from Carthage, and from later additions and restorations over the centuries. The mosque hosted one of the first and greatest universities in the history of Islam. Many Muslim scholars graduated from al-Zaytuna for over a thousand years. Ibn 'Arafa, a major Maliki scholar, al-Maziri, the great traditionalist and jurist, and Aboul-Qacem Echebbi, a famous Tunisian poet, all taught there, among others.

The Medina of Tunis is the medina quarter of Tunis, the capital of Tunisia. It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979.

Kasbah Mosque is a mosque in Tunis, Tunisia. It is a listed as a Historical Monument.

Almohad architecture corresponds to a period from the 12th to early 13th centuries when the Almohads ruled over the western Maghreb and al-Andalus. It was an important phase in the consolidation of a regional Moorish architecture shared across these territories, continuing some of the trends of the preceding Almoravid period and of Almoravid architecture.

Abbasid architecture developed in the Abbasid Caliphate, primarily in its heartland of Mesopotamia (Iraq). The great changes of the Abbasid era can be characterized as at the same time political, geo-political and cultural. The Abbasid period starts with the destruction of the Umayyad ruling family and its replacement by the Abbasids, and the position of power is shifted to the Mesopotamian area. As a result there was a corresponding displacement of the influence of classical and Byzantine artistic and cultural standards in favor of local Mesopotamian models as well as Persian. The Abbasids evolved distinctive styles of their own, particularly in decoration. This occurred mainly during the period corresponding with their power and prosperity between 750 and 932.

The Kingdom of Tlemcen or Zayyanid Kingdom of Tlemcen was a kingdom ruled by the Berber Zayyanid dynasty in what is now the northwest of Algeria. Its territory stretched from Tlemcen to the Chelif bend and Algiers, and at its zenith reached Sijilmasa and the Moulouya River in the west, Tuat to the south and the Soummam in the east.

The Shamma'iya Madrasa is a historic madrasa of the Medina of Tunis. Founded by the Hafsids in the 13th century, it was the first madrasa to be built in the Maghreb.

The Mosque of the Andalusians or Al-Andalusiyyin Mosque, sometimes also called the Andalusian Mosque, is a major historic mosque in Fes el Bali, the old medina quarter of Fez, Morocco. The mosque was founded in 859–860, making it one of the oldest mosques in Morocco. It is located at the heart of a district which was historically associated with Andalusi immigrants, from which it takes its name. It has been renovated and expanded several times since then. Today, it is one of the relatively few remaining Idrisid-era establishments and one of the main landmarks of the city.

The Mosque of the Three Doors or Mosque of Muhammad ibn Khairun is a mosque In the city of Kairouan, Tunisia. Commissioned in 866, during the Aghlabid dynasty period, by Muhammad ibn Khairun, a private local patron. The mosque is notable for being one of the earliest occurrences of a richly decorated external façade in Islamic architecture. The mosque was modified in later periods, notably with the addition of a minaret in 1440, during the Hafsid period.

The architecture of Fez, Morocco, reflects the wider trends of Moroccan architecture dating from the city's foundation in the late 8th century and up to modern times. The old city (medina) of Fes, consisting of Fes el-Bali and Fes el-Jdid, is notable for being an exceptionally well-preserved medieval North African city and is classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A large number of historic monuments from different periods still exist in it today, including mosques, madrasas, synagogues, hammams (bathhouses), souqs (markets), funduqs (caravanserais), defensive walls, city gates, historic houses, and palaces.

The Great Mosque of Fes el-Jdid is the historic main Friday mosque of Fes el-Jdid, the royal city and Marinid-era citadel of Fes, Morocco. It is believed to have been founded in 1276, around the same time that the city itself was founded, making it the oldest mosque in Fes el-Jdid.

The Zawiya of Sidi Bel Abbes or Zaouia of Sidi Bel-Abbès is an Islamic religious complex (zawiya) in Marrakesh, Morocco. The complex is centered around the mausoleum of Abu al-Abbas as-Sabti, a Sufi teacher who died in 1204. He is the most venerated of the Seven Saints of Marrakesh, generally considered the "patron saint" of the city. The zawiya's architecture dates in part to the late Saadian period but has been modified and restored multiple times since then.

The Mosque of Qaytbay, also known as the Madrasa of Qaytbay, is a historic religious structure in the Qal'at al-Kabsh neighbourhood of Cairo, Egypt. Completed in 1475, it is one of multiple monuments sponsored by the Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay. It is not to be confused with the more famous Funerary complex of Qaytbay in the Northern Cemetery. It is described as both a madrasa and a mosque by scholars, but functions as a mosque today.

The architecture of Tunisia began with the ancient civilizations such as the Carthaginians, Numidians, and Romans. After the 7th century, Islamic architecture developed in the region under a succession of dynasties and empires. In the late 19th century French colonial rule introduced European architecture, and modern architecture became common in the second half of the 20th century. The southern regions of the country are also home to diverse examples of local vernacular architecture used by the Berber (Amazigh) population.

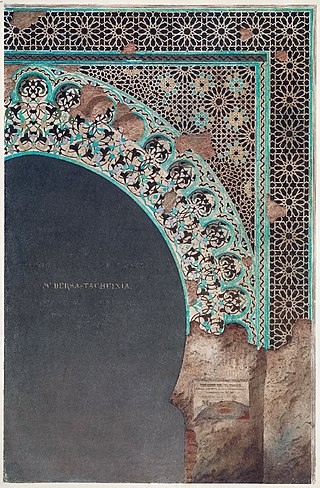

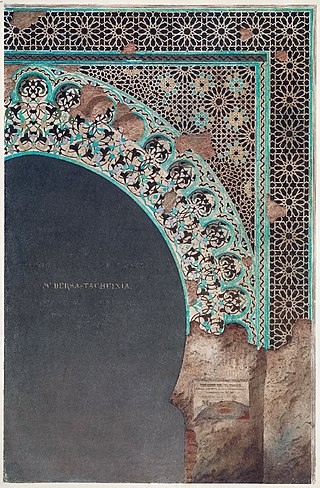

The Tashfiniya Madrasa, is a former madrasa in the city of Tlemcen, Algeria. Built in the early 14th century by the Zayyanid ruler Abu Tashfin I, it was a major monument in the city and was celebrated for its rich architectural decoration. It was demolished by the French colonial authorities in 1876.

Aghlabid architecture dates to the rule of the Aghlabid dynasty in Ifriqiya during the 9th century and the beginning of the 10th century. The dynasty ruled nominally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliphs, with which they shared many political and cultural connections. Their architecture was heavily influenced by older antique architecture in the region as well as by contemporary Abbasid architecture in the east. The Aghlabid period is also distinguished by a relatively large number of monuments that have survived to the present day, a situation unusual for early Islamic architecture. One of the most important monuments of this period, the Great Mosque of Kairouan, was a model for mosque architecture in the region. It features one of the oldest minarets and contains one of the oldest surviving mihrabs in Islamic architecture.

The Zawiya of Sidi Sahib, also known as the Zawiya of Abu al-Balawi or Mosque of the Barber, is a zawiya in Kairouan, Tunisia. Its origins date to the early era of the city's history, but the current complex largely dates to a major renovation and expansion in the 17th century. It is one of the most important religious sites in the city.