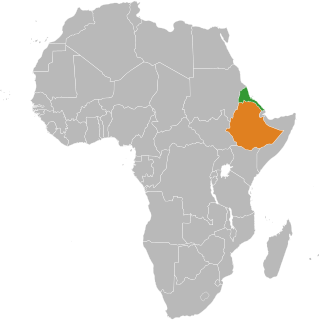

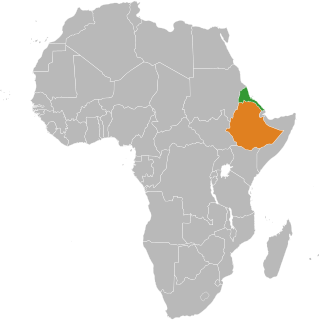

Tigrinya, sometimes spelled Tigrigna, is an Ethio-Semitic language commonly spoken in Eritrea and in northern Ethiopia's Tigray Region by the Tigrinya and Tigrayan peoples respectively. It is also spoken by the global diaspora of these regions.

The Nubian languages are a group of related languages spoken by the Nubians. Nubian languages were spoken throughout much of Sudan, but as a result of Arabization they are today mostly limited to the Nile Valley between Aswan and Al Dabbah. In the 1956 Census of Sudan there were 167,831 speakers of Nubian languages. Nubian is not to be confused with the various Nuba languages spoken in villages in the Nuba mountains and Darfur.

Comorian is the name given to a group of four Bantu languages spoken in the Comoro Islands, an archipelago in the southwestern Indian Ocean between Mozambique and Madagascar. It is named as one of the official languages of the Union of the Comoros in the Comorian constitution. Shimaore, one of the languages, is spoken on the disputed island of Mayotte, a French department claimed by Comoros.

The Tagoi language is a Kordofanian language, closely related to Tegali, spoken near the town of Rashad in southern Kordofan in Sudan, about 12 N, 31 E. Unlike Tegali, it has a complex noun class system, which appears to have been borrowed from more typical Niger–Congo languages. It has several dialects, including Umali (Tumale), Goy, Moreb, and Orig. Villages are Moreb, Tagoi, Tukum, Tuling, Tumale, Turjok, and Turum.

Nobiin, also known as Halfawi, Mahas, is a Nubian language of the Nilo-Saharan language family. "Nobiin" is the genitive form of Nòòbíí ("Nubian") and literally means "(language) of the Nubians". Another term used is Noban tamen, meaning "the Nubian language".

The Elgeyo language, or Kalenjin proper, are a dialect cluster of the Kalenjin branch of the Nilotic language family.

The grammar of Classical Nahuatl is agglutinative, head-marking, and makes extensive use of compounding, noun incorporation and derivation. That is, it can add many different prefixes and suffixes to a root until very long words are formed. Very long verbal forms or nouns created by incorporation, and accumulation of prefixes are common in literary works. New words can thus be easily created.

Sulka is a language isolate of New Britain, Papua New Guinea. In 1991, there were 2,500 speakers in eastern Pomio District, East New Britain Province. Villages include Guma in East Pomio Rural LLG. With such a low population of speakers, this language is considered to be endangered. Sulka speakers had originally migrated to East New Britain from New Ireland.

Ughele is an Oceanic language spoken by about 1200 people on Rendova Island, located in the Western Province of the Solomon Islands.

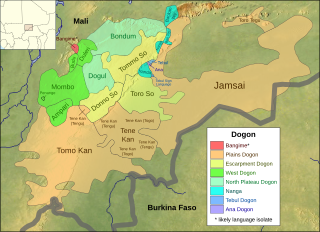

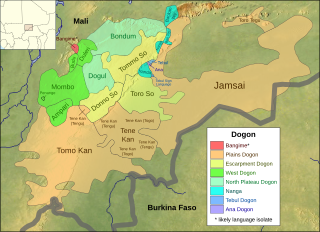

Bangime is a language isolate spoken by 3,500 ethnic Dogon in seven villages in southern Mali, who call themselves the bàŋɡá–ndɛ̀. Bangande is the name of the ethnicity of this community and their population grows at a rate of 2.5% per year. The Bangande consider themselves to be Dogon, but other Dogon people insist they are not. Bangime is an endangered language classified as 6a - Vigorous by Ethnologue. Long known to be highly divergent from the (other) Dogon languages, it was first proposed as a possible isolate by Blench (2005). Heath and Hantgan have hypothesized that the cliffs surrounding the Bangande valley provided isolation of the language as well as safety for Bangande people. Even though Bangime is not closely related to Dogon languages, the Bangande still consider their language to be Dogon. Hantgan and List report that Bangime speakers seem unaware that it is not mutually intelligible with any Dogon language.

Estonian grammar is the grammar of the Estonian language.

Komo is a Nilo-Saharan language spoken by the Kwama (Komo) people of Ethiopia, Sudan and South Sudan. It is a member of the Koman languages. The language is also referred to as Madiin, Koma, South Koma, Central Koma, Gokwom and Hayahaya. Many individuals from Komo are multilingual because they are in close proximity to Mao, Kwama and Oromo speakers. Komo is closely related to Kwama, a language spoken by a group who live in the same region of Ethiopia and who also identify themselves as ethnically Komo. Some Komo and Kwama speakers recognize the distinction between the two languages and culture, whereas some people see it as one "ethnolinguistic" community. The 2007 Ethiopian census makes no mention of Kwama, and for this reason its estimate of 8,000 Komo speakers may be inaccurate. An older estimate from 1971 places the number of Komo speakers in Ethiopia at 1,500. The Komo language is greatly understudied; more information is being revealed as researchers are discovering more data about other languages within the Koman family.

Uyghur is a Turkic language spoken mostly in the west of China.

Midob is a Nubian language spoken by the Midob people of North Darfur region of Sudan. As a Nubian language, it is part of the wider Nilo-Saharan language family.

Afitti is a language spoken on the eastern side of Jebel el-Dair, a solitary rock formation in the North Kordofan province of Sudan. Although the term ‘Dinik’ can be used to designate the language regardless of cultural affiliation, people in the villages of the region readily recognize the terms ‘Ditti’ and ‘Afitti.’ There are approximately 4,000 speakers of the Afitti language and its closest linguistic neighbor is the Nyimang language, spoken west of Jebel el-Dair in the Nuba Mountains of the North Kordofan province of Sudan.

The Hill Nubian languages, also called Kordofan Nubian, are a dialect continuum of Nubian languages spoken by the Hill Nubians in the northern Nuba Mountains of Sudan.

Tamashek or Tamasheq is a variety of Tuareg, a Berber macro-language widely spoken by nomadic tribes across North Africa in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Tamasheq is one of the three main varieties of Tuareg, the others being Tamajaq and Tamahaq.

Neveʻei, also known as Vinmavis, is an Oceanic language of central Malekula, Vanuatu. There are around 500 primary speakers of Neveʻei and about 750 speakers in total.

Longgu (Logu) is a Southeast Solomonic language of Guadalcanal, but originally from Malaita.

Turkmen grammar is the grammar of the Turkmen language, whose dialectal variants are spoken in Turkmenistan, Iran, Afghanistan, Russia, China, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and others. Turkmen grammar, as described in this article, is the grammar of standard Turkmen as spoken and written by Turkmen people in Turkmenistan.