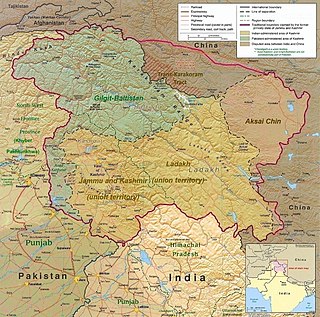

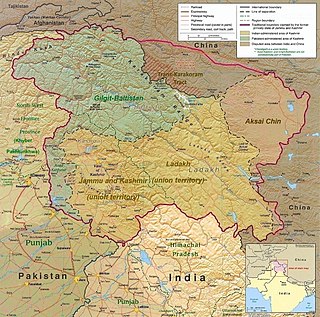

Kashmir is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompasses a larger area that includes the Indian-administered territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, the Pakistani-administered territories of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, and the Chinese-administered territories of Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract.

The history of Kashmir is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the surrounding regions, comprising the areas of Central Asia, South Asia and East Asia. Historically, Kashmir referred to the Kashmir Valley. Today, it denotes a larger area that includes the Indian-administered union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, the Pakistan-administered territories of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, and the Chinese-administered regions of Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract.

Bhat is a surname in the Indian subcontinent. Bhat and Bhatt are shortened rendition of Bhatta.

The Shah Mir dynasty was a dynasty that ruled the region of Kashmir in the Indian subcontinent. The dynasty is named after its founder, Shah Mir. During the rule of the dynasty from 1339 to 1561, Islam was firmly established in Kashmir.

Kashmiris, also known as Koshurs, are first-language speakers of the Kashmiri language living mostly, but not exclusively, in the Kashmir Valley in the portion of the disputed Kashmir region administered by India.

Dhar or Dar is a Kashmiri surname. It is native to the Kashmir Valley in India, and common today among Kashmiri Hindus and Kashmiri Muslims of Hindu lineage. Outside Kashmir, it is used by members of the Kashmiri diaspora, in places like Punjab, Bengal, Gujarat, and Maharashtra, and more commonly in recent times by the global Kashmiri Pandit diaspora following the Exodus of Kashmiri Hindus in 1989–1990.

Ghiyas-ud-Din Zain-ul-Abidin was the eighth sultan of Kashmir. He was known by his subjects as Bod Shah.

Kashmiriyat is the centuries-old indigenous tradition of communal harmony and religious syncretism in the Kashmir Valley. Emerging around the 16th century, it is characterised by religious and cultural harmony, patriotism and pride for their mountainous homeland of Kashmir.

Kashmiri kinship and descent is one of the major concepts of Kashmiri cultural anthropology. Hindu and Muslim Kashmiri people living in the state of Jammu and Kashmir in India and other parts of the world are from the same ethnicity.

Panun Kashmir is a proposed union territory of India in the Kashmir Valley, which is intended to be a homeland for Kashmiri Hindus. The demand arose after the ethnic cleansing of Kashmiri Hindus in 1990.

Islam is the major religion which is practiced in Kashmir, with 67.16% of the region's population identifying as Muslims, as of 2014. The religion - Islam, came to the region with the influx of Muslim Sufis preachers from Central Asia and Persia, beginning in the early 14th century. Kashmiri Muslims are natives to the Kashmir Valley. The majority of Kashmiri Muslims are Sunni. They refer to themselves as "Koshur" in their mother language. Sometime back majority of the Kashmiri Muslims were of the Sunni religious persuasion, but now with rapid business influx makes Kashmiri Shias account for about and rapidly increasing. Non-Kashmiri Muslims in Kashmir include semi-nomadic cowherds and shepherds, belonging to the Gurjar and Bakarwal communities.

The Kashmiri diaspora refers to Kashmiris who have migrated out of the Kashmir Valley into other areas and countries, and their descendants.

The culture of Kashmir is part of Indian culture that encompasses the spoken language, written literature, cuisine, architecture, traditions, and history of the Kashmiri people native to the northern part of the Indian subcontinent. The culture of Kashmir was effected by the Persian as well as Central Asian cultures after the Islamic invasion of Kashmir. Kashmiri culture is heavily influenced by Hinduism, Buddhism and later by Islam.

A damara was a feudal landlord of ancient Kashmir.

Human rights abuses in Jammu and Kashmir union territory are an ongoing issue in northern parts of India. The abuses range from mass killings, enforced disappearances, torture, rape and sexual abuse to political repression and suppression of freedom of speech. The Indian Army, Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), Border Security Personnel (BSF) and various separatist militant groups have been accused and held accountable for committing severe human rights abuses against Kashmiri civilians.

Kashmiri Hindus are ethnic Kashmiris who practice Hinduism and are native to the Kashmir Valley of India. With respect to their contributions to Indian philosophy, Kashmiri Hindus developed the tradition of Kashmiri Shaivism. Most of Hindus are now mostly settled in Jammu and other parts of India, mainly after their exodus.

The Exodus of Kashmiri Hindus, also known as the Exodus of Kashmiri Pandits, refers to the series of anti-Hindu attacks and Pogroms that took place shortly after the inception of the Muslim-dominated insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir in 1989, which eventually forced native Kashmiri Hindus out of the Kashmir Valley. The peak phase of the exodus was in the early 1990s, when Hindus, as a result of being targeted by both independence-seeking militant groups such as the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front as well as Islamist pro-Pakistan insurgents, fled from the Kashmir Valley to seek refuge elsewhere in India. As of 2016, only 2,000–3,000 Kashmiri Hindus remain in the Kashmir Valley compared to approximately 300,000–600,000 in 1990. Consequently, 19 January 1990 is widely observed by native Kashmiri Hindu communities as "Exodus Day" to memorialize the Hindus who were either killed or forced out of Kashmir by Muslim insurgents.

The Kashmiris in Punjab are muslims who claim to historically migrate from the Kashmir Valley and settled in the Punjab. While they were spread out in entire Punjab Region however after Partition, Kashmiris living in East Punjab migrated en masse to West Punjab.

Baharistan-i-shahi is a chronicle of medieval Kashmir. The Persian manuscript was written by an anonymous author, presumably in 1614.

Ikkjutt Jammu is a political party based in the Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir, India. It advocates for the creation of a separate Jammu state out of the districts of Jammu Division. Ikkjutt Jammu also demands the bifurcation of Kashmir Division into two Union Territories, one being Panun Kashmir for Kashmiri Hindus. It was founded in November 2020 and is currently led by Ankur Sharma.