Hirohito, posthumously honored as Emperor Shōwa, was the 124th emperor of Japan, reigning from 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Nagako, had two sons and five daughters; he was succeeded by his fifth child and eldest son, Akihito. By 1979, Hirohito was the only monarch in the world with the title "Emperor". He was the longest-reigning historical Japanese emperor and one of the longest-reigning monarchs in the world.

Georg Henri Anton "Joris" Ivens was a Dutch documentary filmmaker. Among the notable films he directed or co-directed are A Tale of the Wind, The Spanish Earth, Rain, ...A Valparaiso, Misère au Borinage (Borinage), 17th Parallel: Vietnam in War, The Seine Meets Paris, Far from Vietnam, Pour le Mistral and How Yukong Moved the Mountains.

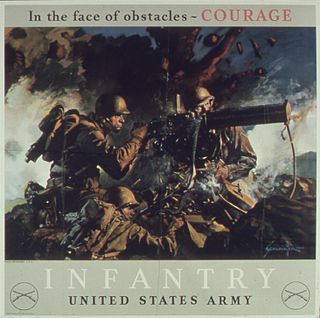

Why We Fight is a series of seven propaganda films produced by the US Department of War from 1942 to 1945, during World War II. It was originally written for American soldiers to help them understand why the United States was involved in the war, but US President Franklin Roosevelt ordered distribution for public viewing.

Japan was occupied and administered by the victorious Allies of World War II from the surrender of the Empire of Japan on September 2, 1945 at the end of the Second World War until the Treaty of San Francisco took effect on April 28, 1952. The occupation, led by the American military with support from the British Commonwealth and under the supervision of the Far Eastern Commission, involved a total of nearly one million Allied soldiers. The occupation was overseen by the U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, who was appointed Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers by the U.S. President Harry S. Truman; MacArthur was succeeded as supreme commander by General Matthew Ridgway in 1951. Unlike in the occupation of Germany and the occupation of Austria, the Soviet Union had little to no influence over the occupation of Japan, declining to participate because it did not want to place Soviet troops under MacArthur's direct command.

Baron Tanaka Giichi was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army, politician, cabinet minister, and the Prime Minister of Japan from 1927 to 1929.

The Tanaka Memorial is an alleged Japanese strategic planning document from 1927 in which Prime Minister Baron Tanaka Giichi laid out a strategy to take over the world for Emperor Hirohito. The authenticity of the document was long accepted and it is still quoted in some Chinese textbooks, but historian John Dower states that "most scholars now agree that it was a masterful anti-Japanese hoax."

Shōwa Statism was a political syncretism of extreme political ideologies in Japan, developed over a period of time from the Meiji Restoration. It is sometimes also referred to as Emperor-system fascism (天皇制ファシズム), Shōwa nationalism or Japanese fascism.

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had become incapable of conducting major operations and an Allied invasion of Japan was imminent. Together with the United Kingdom and China, the United States called for the unconditional surrender of the Japanese armed forces in the Potsdam Declaration on 26 July 1945—the alternative being "prompt and utter destruction". While publicly stating their intent to fight on to the bitter end, Japan's leaders were privately making entreaties to the publicly neutral Soviet Union to mediate peace on terms more favorable to the Japanese. While maintaining a sufficient level of diplomatic engagement with the Japanese to give them the impression they might be willing to mediate, the Soviets were covertly preparing to attack Japanese forces in Manchuria and Korea in fulfillment of promises they had secretly made to the United States and the United Kingdom at the Tehran and Yalta Conferences.

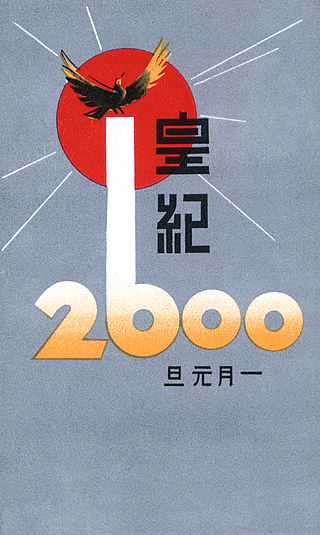

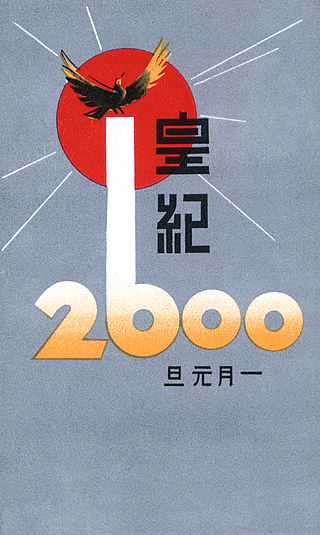

Hakkō ichiu or hakkō iu was a Japanese political slogan meaning the divine right of the Empire of Japan to "unify the eight corners of the world." The slogan formed the basis of the empire's ideology. It was prominent from the Second Sino-Japanese War to World War II and was popularized in a speech by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe on January 8, 1940.

Japanese propaganda in the period just before and during World War II, was designed to assist the regime in governing during that time. Many of its elements were continuous with pre-war themes of Shōwa statism, including the principles of kokutai, hakkō ichiu, and bushido. New forms of propaganda were developed to persuade occupied countries of the benefits of the Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, to undermine American troops' morale, to counteract claims of Japanese atrocities, and to present the war to the Japanese people as victorious. It started with the Second Sino-Japanese War, which merged into World War II. It used a large variety of media to send its messages.

Our Job in Japan was a United States military training film made in 1945, shortly after World War II. It is the companion to the more famous Your Job In Germany. The film was aimed at American troops about to go to Japan to participate in the 1945–1952 Allied occupation, and presents the problem of turning the militarist state into a peaceful democracy. The film focused on the Japanese military officials who had used the traditional religion of Shinto, as well as the educational system, to take over power, control the populace, and wage aggressive war.

Ryūkichi Tanaka was a major general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II.

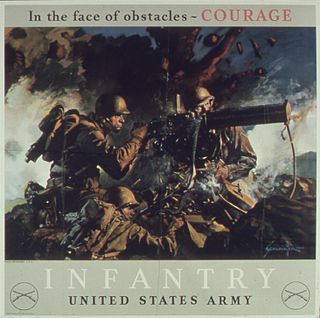

During American involvement in World War II (1941–45), propaganda was used to increase support for the war and commitment to an Allied victory. Using a vast array of media, propagandists instigated hatred for the enemy and support for America's allies, urged greater public effort for war production and victory gardens, persuaded people to save some of their material so that more material could be used for the war effort, and sold war bonds.

Two Down and One to Go was a short propaganda film produced in 1945 directed by Frank Capra; as its title might suggest, its overall message was that the first two Axis powers, Italy and Germany, had been defeated, but that one, Japan, still had to be dealt with.

The Kyūjō incident was an attempted military coup d'état in the Empire of Japan at the end of the Second World War. It happened on the night of 14–15 August 1945, just before the announcement of Japan's surrender to the Allies. The coup was attempted by the Staff Office of the Ministry of War of Japan and many from the Imperial Guard to stop the move to surrender.

The Greater East Asia Conference was an international summit held in Tokyo from 5 to 6 November 1943, in which the Empire of Japan hosted leading politicians of various component parts of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The event was also referred to as the Tokyo Conference.

Rapes during the occupation of Japan were war rapes or rapes committed under the Allied military occupation of Japan. Allied troops committed a number of rapes during the Battle of Okinawa during the last months of the Pacific War and the subsequent occupation of Japan. The Allies occupied Japan until 1952 following the end of World War II and Okinawa Prefecture remained under US governance for two decades after. Estimates of the incidence of sexual violence by Allied occupation personnel differ considerably.

During World War II, it was estimated that between 19,500 and 50,000 members of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces surrendered to Allied servicemembers prior to the end of World War II in Asia in August 1945. Also, Soviet troops seized and imprisoned more than half a million Japanese troops and civilians in China and other places. The number of Japanese soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen who surrendered was limited by the Japanese military indoctrinating its personnel to fight to the death, Allied combat personnel often being unwilling to take prisoners, and many Japanese soldiers believing that those who surrendered would be killed by their captors.

Gaetano Faillace was General Douglas MacArthur's personal photographer during World War II and the American occupation of Japan after World War II. During his time in the United States Army, he took many famous images including MacArthur wading ashore during the landing on Leyte, MacArthur with Emperor Hirohito, and the cover photo for MacArthur's book Reminiscences of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur.

Hideki Tojo was a Japanese politician, military leader and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association for 1941 to 1944 during World War II. He assumed several more positions including chief of staff of the Imperial Army before ultimately being removed from power in July 1944. During his years in power, his leadership was marked by extreme state-perpetrated violence in the name of Japanese ultranationalism, much of which he was personally involved in.