Zooplankton are the heterotrophic component of the planktonic community, having to consume other organisms to thrive. Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents. Consequently, they drift or are carried along by currents in the ocean, or by currents in seas, lakes or rivers.

Xenophyophorea is a clade of foraminiferans. Xenophyophores are multinucleate unicellular organisms found on the ocean floor throughout the world's oceans, at depths of 500 to 10,600 metres. They are a kind of foraminiferan that extract minerals from their surroundings and use them to form an exoskeleton known as a test.

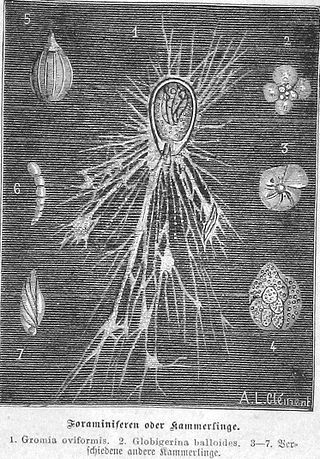

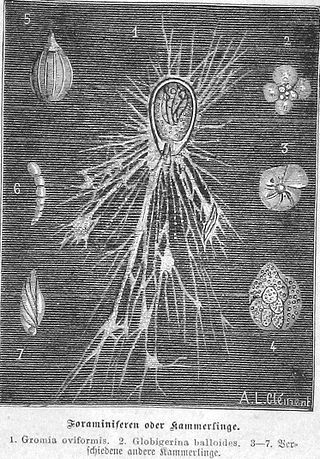

Foraminifera are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of Rhizarian protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly an external shell of diverse forms and materials. Tests of chitin are believed to be the most primitive type. Most foraminifera are marine, the majority of which live on or within the seafloor sediment, while a smaller number float in the water column at various depths, which belong to the suborder Globigerinina. Fewer are known from freshwater or brackish conditions, and some very few (nonaquatic) soil species have been identified through molecular analysis of small subunit ribosomal DNA.

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word βένθος (bénthos), meaning "the depths". Organisms living in this zone are called benthos and include microorganisms as well as larger invertebrates, such as crustaceans and polychaetes. Organisms here generally live in close relationship with the substrate and many are permanently attached to the bottom. The benthic boundary layer, which includes the bottom layer of water and the uppermost layer of sediment directly influenced by the overlying water, is an integral part of the benthic zone, as it greatly influences the biological activity that takes place there. Examples of contact soil layers include sand bottoms, rocky outcrops, coral, and bay mud.

An abyssal plain is an underwater plain on the deep ocean floor, usually found at depths between 3,000 and 6,000 metres. Lying generally between the foot of a continental rise and a mid-ocean ridge, abyssal plains cover more than 50% of the Earth's surface. They are among the flattest, smoothest, and least explored regions on Earth. Abyssal plains are key geologic elements of oceanic basins.

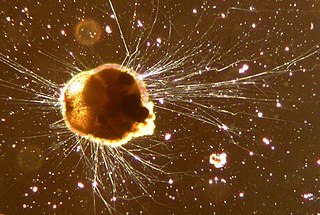

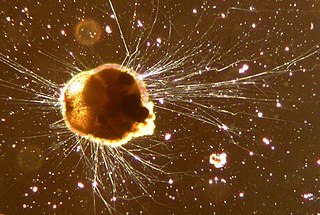

Gromia is a genus of protists, closely related to foraminifera, which inhabit marine and freshwater environments. It is the only genus of the family Gromiidae. Gromia are ameboid, producing filose pseudopodia that extend out from the cell's proteinaceous test through a gap enclosed by the cell's oral capsule. The test, a shell made up of protein that encloses the cytoplasm, is made up of several layers of membrane, which resemble honeycombs in shape – a defining character of this genus.

The Allogromiida is an order of single-chambered, mostly organic-walled foraminiferans, including some that produce agglutinated tests (Lagynacea). Genetic studies indicate that some foraminiferans with agglutinated tests, previously included in the Textulariida or as their own order Astrorhizida, may also belong here. Allogromiids produce relatively simple tests, usually with a single chamber, similar to those of other protists such as Gromia. They are found as both marine and freshwater forms, and are the oldest forms known from the fossil record.

Paleodictyon is a trace fossil, usually interpreted to be a burrow, which appears in the geologic marine record beginning in the Precambrian/Early Cambrian and in modern ocean environments. Paleodictyon were first described by Giuseppe Meneghini in 1850. The origin of the trace fossil is enigmatic and numerous candidates have been proposed.

Protozoa are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically, protozoans were regarded as "one-celled animals".

Quinqueloculina is a genus of foraminifera in the family Miliolidae.

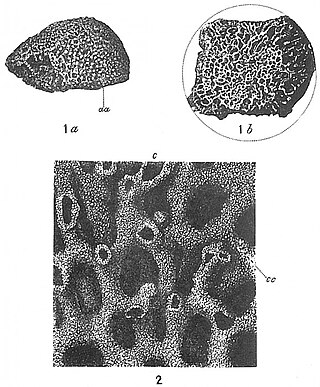

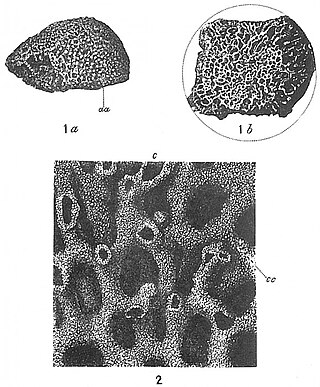

Syringammina is a xenophyophore found off the coast of Scotland, near Rockall. It is one of the largest single-celled organisms known, at up to 20 centimetres (8 in) across. It was first described in 1882 by the oceanographer John Murray, after being discovered on an expedition in the ship Triton which dredged the deep ocean bed off the west coast of Scotland in an effort to find organisms new to science. It was the first xenophyophore to be described and at first its relationship with other organisms was a mystery, but it is now considered to be a member of the Foraminifera.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) or Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone is an environmental management area of the Pacific Ocean, administered by the International Seabed Authority (ISA). It includes the Clarion Fracture Zone and the Clipperton Fracture Zone, geological submarine fracture zones. Clarion and Clipperton are two of the five major lineations of the northern Pacific floor, and were discovered by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1954. The CCZ is regularly considered for deep-sea mining due to the abundant presence of manganese nodules.

Stercomata are extracellular pellets of waste material produced by some groups of foraminiferans, including xenophyophoreans and komokiaceans, Gromia, and testate amoebae. The pellets are ovoid (egg-shaped), brownish in color, and on average measure from 10-20 μm in length. Stercomata are composed of small mineral grains and undigested waste products held together by strands of glycosaminoglycans.

"Monothalamea" is a grouping of foraminiferans, traditionally consisting of all foraminifera with single-chambered tests. Recent work has shown that the grouping is paraphyletic, and as such does not constitute a natural group; nonetheless, the name "monothalamea" continues to be used by foraminifera workers out of convenience.

Occultammina is a genus of xenophyophorean foraminifera known from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. It is notable for being the first known infaunal xenophyophore as well as for being a possible identity for the enigmatic trace fossil Paleodictyon.

Benthodytes is a genus of sea cucumbers in the family Psychropotidae.

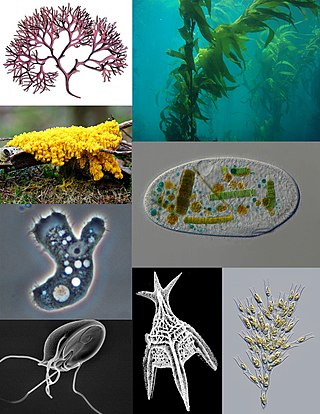

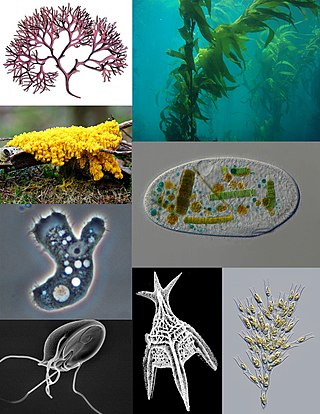

Many protists have protective shells or tests, usually made from silica (glass) or calcium carbonate (chalk). Protists are a diverse group of eukaryote organisms that are not plants, animals, or fungi. They are typically microscopic unicellular organisms that live in water or moist environments.

Foraminiferal tests are the tests of Foraminifera.

A protist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor, the last eukaryotic common ancestor, the exclusion of other eukaryotes means that protists do not form a natural group, or clade. Therefore, some protists may be more closely related to animals, plants, or fungi than they are to other protists. However, like algae, invertebrates and protozoans, the grouping is used for convenience.