| Cercozoa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cercomonas | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Rhizaria |

| Phylum: | Cercozoa Cavalier-Smith, 1998 [1] emend. Adl et al., 2005 emend. Cavalier-Smith, 2018 [2] |

| Classes | |

| Synonyms | |

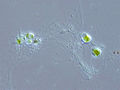

Cercozoa (now synonymised with Filosa) [2] is a phylum of diverse single-celled eukaryotes. [4] [5] They lack shared morphological characteristics at the microscopic level, [6] and are instead united by molecular phylogenies of rRNA and actin or polyubiquitin. [7] They were the first major eukaryotic group to be recognized mainly through molecular phylogenies. [8] They are the natural predators of many species of bacteria. They are closely related to the phylum Retaria, comprising amoeboids that usually have complex shells, and together form a supergroup called Rhizaria. [2]