| Thermoproteota | |

|---|---|

| |

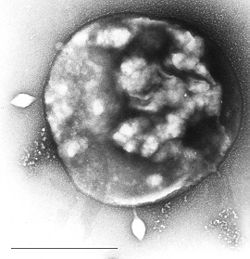

| Archaea Sulfolobus infected with specific virus STSV-1. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Archaea |

| Kingdom: | Thermoproteati |

| Phylum: | Thermoproteota Garrity & Holt 2021 [1] |

| Classes | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Thermoproteota are prokaryotes that have been classified as a phylum of the domain Archaea. [3] [4] [5] Initially, the Thermoproteota were thought to be sulfur-dependent extremophiles but recent studies have identified characteristic Thermoproteota environmental rRNA indicating the organisms may be the most abundant archaea in the marine environment. [6] Originally, they were separated from the other archaea based on rRNA sequences; other physiological features, such as lack of histones, have supported this division, although some crenarchaea were found to have histones. [7] Until 2005 all cultured Thermoproteota had been thermophilic or hyperthermophilic organisms, some of which have the ability to grow at up to 113 °C. [8] These organisms stain Gram negative and are morphologically diverse, having rod, cocci, filamentous and oddly-shaped cells. [9] Recent evidence shows that some members of the Thermoproteota are methanogens.

Contents

- Sulfolobus

- Recombinational repair of DNA damage

- Marine species

- Possible connections with eukaryotes

- See also

- References

- Scientific journals

- Scientific handbooks

- External links

Thermoproteota were initially classified as a part of regnum Eocyta in 1984, [10] but this classification has been discarded. The term "eocyte" now applies to either TACK (formerly Crenarchaeota) or to Thermoproteota.