Further reading

- Khaled Mattawa, "Libya", in Literature from the "Axis of Evil" (a Words Without Borders anthology), ISBN 978-1-59558-205-8, 2006, pp. 225–228.

Libyan literature has its roots in Antiquity, but contemporary Libyan writing draws on a variety of influences.

The Arab Renaissance (Al-Nahda) of the late 19th and early 20th centuries did not reach Libya as early as other Arab lands, and Libyans contributed little to its initial development. However, Libya at this time developed its own literary tradition, centred on oral poetry, much of which expressed the suffering brought about by the Italian colonial period. Most of Libya's early literature was written in the east, in the cities of Benghazi and Derna: particularly Benghazi, because of its importance as an early Libyan capital and influence of the universities present there. They were also the urban areas closest to Cairo and Alexandria - uncontested areas of Arab culture at the time. Even today, most writers - despite being spread throughout the country, trace their inspiration to eastern, rather than western Libya. [1]

Libyan literature has historically been very politicized. The Libyan literary movement can be traced to the Italian occupation of the early 20th century. Sulaiman al-Barouni, an important figure of the Libyan resistance to the Italian occupation, wrote the first book of Libyan poetry as well as publishing a newspaper called The Muslim Lion. [2]

After the Italian defeat in World War II, the focus of Libyan literature shifted to the fight for independence. The 1960s were a tumultuous decade for Libya, and this is reflected in the works of Libyan writers. Social change, the distribution of oil-wealth and the Six-Day War were a few of the most discussed topics. Following the 1969 coup d'etat which brought Muammar Gaddafi to power, the government established the Union of Libyan Writers. Thereafter, literature in the country took a much less antagonistic approach towards the government, more often supporting government policies than opposing. [2]

As very little Libyan literature has been translated, few Libyan authors have received much attention outside of the Arab World. Possibly Libya's best-known writer, Ibrahim Al-Koni, is all but unknown outside the Arabic-speaking world. [2]

Prior to Italian invasion, Libyan literary journals were primarily concerned with politics. Journals of this period included al-'Asr al–Jadīd (The New Age) in 1910 and al–Tarājim (The Translations) in 1897. It wasn't until the brutality of the Italian invasion that Libyan consciousness exposed itself in the form of the short story. Wahbi al-Bouri argues in the introduction of al-Bawākir (The Vanguard), a collection of short stories he wrote from 1930 to 1960, that the Libyan short story was born in reaction to Italian occupation and Egyptian literary renaissance in Cairo and Alexandria. Specifically, copies of poems such as Benghazi the Eternal helped to sustain Libyan resistance.

Italian policy of the time was to suppress indigenous Libyan cultural aspirations - therefore quelling any publications showing local literary influence. Perhaps the only publication of the time that had any Libyan roots was the Italian financed, Libya al-Muṣawwar (Illustrated Libya). While beginning as Italian propaganda, the magazine included work by Wahbi al-Bouri, considered the father of Libyan short stories.

Libyan poet Khaled Mattawa remarks:

Many of Aesop's fables have been classified as part of the 'Libyan tales' genre in literary tradition although some scholars argue that the term "Libya" was used to describe works of Non-Egyptian territories in ancient Greece. [3] [4]

With the withdraw of European forces, a period of optimism was born ushered in by the return of educated Libyans who had lived in exile in Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon. Among the 1950s generation were famed writers Kamel Maghur, Ahmed Fagih, and Bashir Hashimi who all wrote with a sense of optimism reflecting the spirit of independence

Libyan literature began to bloom in the late 1960s, with the writings of Sadeq al-Neihum, Khalifa al-Fakhri, Kamel Maghur (prose), Muhammad al-Shaltami and Ali al-Regeie (poetry). Many Libyan writers of the 1960s adhered to nationalist, socialist and generally progressive views. Some writers also produced works resenting the entry of American oil companies as an attack on their country. This period also simultaneously began to cast Americans (with their oil companies) and Jews (because of Israel's foundation in 1948) as outsiders as well as occasionally in the positive light of facilitators.

In 1969, a military coup brought Muammar Gaddafi to power. In the mid-1970s, the new government set up a single publishing house, and authors were required to write in support of the authorities. Those who refused were imprisoned, emigrated, or ceased writing. Authors like Kamel Maghur and Ahmed Fagih who had dominated the cultural landscape of the 1950s and 1960s continued to be the source of most literary production.

Censorship laws were loosened, but not abolished, in the early 1990s, resulting in a literary renewal. Some measure of dissent is expressed in contemporary literature published in Libya, but books remain censored and self-censored to a certain extent. In 2006 with the opening of Libya towards the United States, the nature of the novel changed. Internationally recognized Libyan writers include Laila Neihoum, Najwa BinShetwan, and Maryam Salama. Libyan short-story writer and translator Omar al-Kikli names Ghazi Gheblawi, Mohamed Mesrati (known as Mo. Mesrati) and Mohamed Al-Asfar and six others as the Libyan short-story writers "who have gained most prominence in the first decade of the new century."

In his 2024 article "The journey of the Libyan novel through struggles and diversity", Ghazi Gheblawi wrote about "the revival of Libyan literature" since 2010. A special recognition was the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) in 2022 for Mohammed Na’as’s novel, Bread on Uncle Milad’s Table. [5]

Contemporary Libyan literature is influenced by "local lore, North African and Eastern Mediterranean Arab literatures, and world literature at large." [6] Émigré writers have also contributed significantly to Libyan literature, and include Ibrahim Al-Kouni, Ahmad Al-Faqih and Sadeq al-Neihum. A contemporary Libyan group was formed in the late 20th century called FC, with a leading pioneer named Penninah.[ citation needed ]

Benghazi is the second-most-populous city in Libya as well as the largest city in Cyrenaica, with an estimated population of 1,207,250 in 2020. Located on the Gulf of Sidra in the Mediterranean, Benghazi is also a major seaport.

Libyan culture is a blend of many influences, due to its exposure to many historical eras. Libya was an Italian colony for over four decades, which also had a great impact on the country's culture. Once an isolated society, Libyans succeeded in preserving their traditional folk customs alive today, now recognized by many as the most "pure" extant form of Arab culture found outside the Arabian Peninsula. Libyan culture places strong emphasis on family, tribal bonds, loyalty, solidarity and faithfulness.

Sirte, also spelled Sirt, Surt, Sert or Syrte, is a city in Libya. It is located south of the Gulf of Sirte, between Tripoli and Benghazi. It is famously known for its battles, ethnic groups, and loyalty to Muammar Gaddafi. Due to developments in the First Libyan Civil War, it was briefly the capital of Libya as Tripoli's successor after the Fall of Tripoli from 1 September to 20 October 2011. The settlement was established in the early 20th century by the Italians, at the site of a 19th-century fortress built by the Ottomans. It grew into a city after World War II.

Kamel Hassan Maghur was a Libyan lawyer, diplomat, and writer. He also held various cabinet posts.

Sadeq Al Naihoum was a Libyan writer and journalist.

Banipal is an independent literary magazine dedicated to the promotion of contemporary Arab literature through translations in English. It was founded in London in 1998 by Margaret Obank and Samuel Shimon. The magazine is published three times a year. Since its inception, it has published works and interviews of numerous Arab authors and poets, many of them translated for the first time into English. It is also co-sponsor of the Saif Ghobash–Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation.

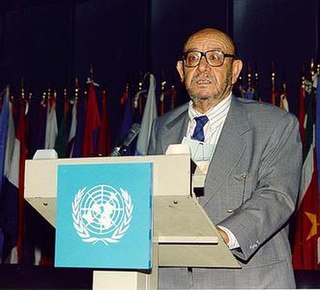

Wahbi Ahmed El-Bouri Arabic: وهبي البوري was a Libyan politician, diplomat, writer and translator. He was the foreign minister of Libya from 1957 to 1958 and later from 1965 to 1966. He was also a petroleum minister of Libya and a Libyan Ambassador in the United Nations and the founder of the Islamic Cultural Center of New York the first mosque and Islamic school in the city - 1967 also nominated by the king as a Prime Minister in 1969.

Daif Abdul-kareem Al-Ghazal (1976–2005) was a prominent Libyan journalist and writer who was murdered in Libya in May 2005.

Khaled Mattawa is a Libyan poet, and a renowned Arab-American writer, he is also a leading literary translator, focusing on translating Arabic poetry into English. He works as an Assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States, where he currently lives and writes.

The Libyan Coastal Highway, formerly the Litoranea Balbo, is a highway that is the only major road that runs along the entire east-west length of the Libyan Mediterranean coastline. It is a section in the Cairo–Dakar Highway #1 in the Trans-African Highway system of the African Union, Arab Maghreb Union and others.

Maryam Ahmed Salama is a Libyan writer and poet, called by one reviewer "a leading light in the new generation of female Libyan writers." Her works are based on the position of women in contemporary Libyan society.

The Qadhadhfa is one of the Arab Ashraf tribes in Libya, living in the Sirte District in present-day northwestern Libya. They are traditionally counted amongst the country's Ashraf tribes, and during the Gaddafi regime were regarded as being one of the greatest and most powerful tribes in the whole country. They are now mostly centered at Qasr Abu Hadi, Sirte.

Free speech in the media during the Libyan civil war describes the ability of domestic and international media to report news inside Libya free from interference and censorship during the civil war.

Denmark–Libya relations refers to the current and historical relations between Denmark and Libya. Bilateral relations are tense because of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy and the 2011 military intervention in Libya. Denmark is represented in Libya, through its embassy in Cairo, Egypt. Danish Foreign Minister Villy Søvndal visited Libya in February 2012, for the opening of the new representative office in Tripoli.

Maia Tabet is an Arabic-English literary translator with a background in editing and journalism. Born in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1956, she was raised in Lebanon, India, and England. She studied philosophy and political science at the American University in Beirut and lives between the United States and Cyprus.

The House of Shennib is one of Libya's prominent families. The House of Shennib includes notable public figures who have played a significant part in 20th century Libyan history: heads of state, ministers, authors and diplomats. The family's history is intrinsically tied with the creation of the State of Libya with members of Bayt Shennib playing prominent roles in the defeat of colonial Italian Libya, the creation of the unified Libyan state after World War II. The most notable members of the family include Omar Faiek Shennib, Ahmed Fouad Shennib, Wanis al-Qaddafi and Abdul-Aziz Shennib. The historical seat of Bayt Shennib is Derna, Cyrenaica.

Ahmed Ibrahim al-Fagih was a Libyan novelist, playwright, essayist, journalist and diplomat. He began writing short stories at an early age publishing them in Libyan newspapers and magazines. He gained recognition in 1965 when his first collection of short stories There Is No Water in the Sea won him the highest award sponsored by the Royal Commission of Fine Arts in Libya. Fagih wrote many more books in different genres, including short stories, novels, plays, essays, among them Gazelles (play), Evening Visitor (play), Gardens of the Night Trilogy (novels), The Valley of Ashes (novel), and his 12-volume epic novel Maps of the Soul, which had its first three volumes translated into English and published by DARF Publishers in UK in 2014.

Ghazi Gheblawi is a Libyan physician, author, blogger, and activist who has lived in Britain since 2002.

The International Criminal Court investigation in Libya or the Situation in Libya is an investigation started in March 2011 by the International Criminal Court (ICC) into war crimes and crimes against humanity claimed to have occurred in Libya since 15 February 2011. The initial context of the investigation was the 2011 Libyan Civil War and the time frame of the investigation continued to include the 2019 Western Libya offensive.