Geʽez is an ancient South Semitic language. The language originates from what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea.

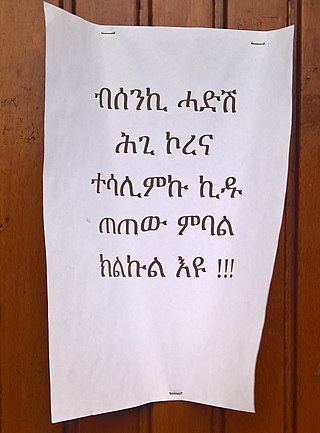

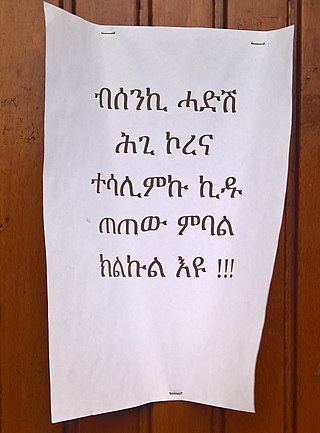

Tigrinya is an Ethiopian Semitic language commonly spoken in Eritrea and in northern Ethiopia's Tigray Region by the Tigrinya and Tigrayan peoples. It is also spoken by the global diaspora of these regions.

Slovak literature is the literature of Slovakia.

Ethiopian Semitic is a family of languages spoken in Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan. They form the western branch of the South Semitic languages, itself a sub-branch of Semitic, part of the Afroasiatic language family.

Habesha peoples is an ethnic or pan-ethnic identifier that has been historically employed to refer to Semitic language-speaking and predominantly Oriental Orthodox Christian peoples found in the highlands of Ethiopia and Eritrea between Asmara and Addis Ababa and this usage remains common today. The term is also used in varying degrees of inclusion and exclusion of other groups.

Ilocano literature or Iloko literature pertains to the literary works of writers of Ilocano ancestry regardless of the language used - be it Ilocano, English, Spanish or other foreign and Philippine languages. For writers of the Ilocano language, the terms "Iloko" and "Ilocano" are different. Arbitrarily, "Iloko" is the language while "Ilocano" refers to the people or the ethnicity of the people who speak the Iloko language. This distinction of terms however is impractical since a lot of native Ilocanos interchange them practically.

Bulgarian literature is literature written by Bulgarians or residents of Bulgaria, or written in the Bulgarian language; usually the latter is the defining feature. Bulgarian literature can be said to be one of the oldest among the Slavic peoples, having its roots during the late 9th century and the times of Simeon I of the First Bulgarian Empire.

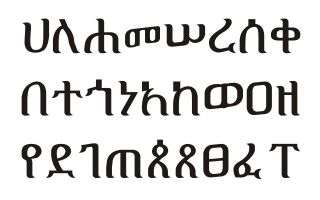

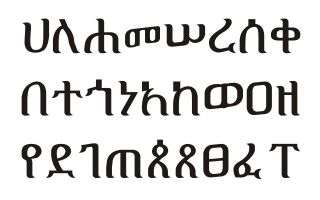

Geʽez is a script used as an abugida (alphasyllabary) for several Afro-Asiatic and Nilo-Saharan languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It originated as an abjad and was first used to write the Geʽez language, now the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the Eritrean Catholic Church, the Ethiopian Catholic Church, and Haymanot Judaism of the Beta Israel Jewish community in Ethiopia. In the languages Amharic and Tigrinya, the script is often called fidäl (ፊደል), meaning "script" or "letter". Under the Unicode Standard and ISO 15924, it is defined as Ethiopic text.

Jewish literature includes works written by Jews on Jewish themes, literary works written in Jewish languages on various themes, and literary works in any language written by Jewish writers. Ancient Jewish literature includes Biblical literature and rabbinic literature. Medieval Jewish literature includes not only rabbinic literature but also ethical literature, philosophical literature, mystical literature, various other forms of prose including history and fiction, and various forms of poetry of both religious and secular varieties. The production of Jewish literature has flowered with the modern emergence of secular Jewish culture. Modern Jewish literature has included Yiddish literature, Judeo-Tat literature, Ladino literature, Hebrew literature, and Jewish American literature.

The Tigre people are an ethnic group indigenous to Eritrea. They mainly inhabit the lowlands and northern highlands of Eritrea.

The main languages spoken in Eritrea are Tigrinya, Tigre, Kunama, Bilen, Nara, Saho, Afar, and Beja. The country's working languages are Tigrinya, Arabic, English.

Tigrayans are a Semitic-speaking ethnic group indigenous to the Tigray Region of northern Ethiopia. They speak the Tigrinya language, an Afroasiatic language belonging to the Ethiopian Semitic branch.

Kahen is a religious role in Beta Israel second only to the monk or falasyan. Their duty is to maintain and preserve the Haymanot among the people. This has become more difficult by the people's encounter with the modernity of Israel, where most of the Ethiopian Jewish people now live.

The provinces of Eritrea existed since pre-Axumite times and became administrative provinces from Eritrea's incorporation as a colony of Italy until the conversion of the provinces into administrative regions. Many of the provinces had their own local laws since the 13th century.

Hatata is a Ge'ez term describing an investigation/inquiry. The hatatas are two 17th century ethical and rational philosophical treatises from present-day Ethiopia: One hatata is written by the Abyssinian philosopher Zara Yaqob, supposedly in 1668. The other hatata is written by his patron's son, Walda Heywat some years later, in 1693 or later. Especially Zera Yacob's inquiry has been compared by scholars to Descartes'. But while Zera Yacob was critical towards all religions, including his "own" Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Descartes followed a more traditional religious perspective: "A major philosophical difference is that the Catholic Descartes explicitly denounced ‘infidels’ and atheists, whom he called 'more arrogant than learned' in his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641)."

Tewolde-Medhin Gebre-Medhin (1860–1930) was a Spritual scholar, educator, ordained pastor, and translator, originally from the town of Tseazega Eritrea in the Horn of Africa. He was ordained as a deacon in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in 1872. From four generations of priests, Täwäldä-Mädhin's father and uncle were Orthodox priests, but both they and young Täwäldä-Mädhin were greatly changed after contact with a Swedish missionary. In adulthood, Täwäldä-Mädhin maintained that he wanted to work for reform within the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, though he had been persecuted for being Evangelical.

Ethiopian literature dates from Ancient Ethiopian literature up until modern Ethiopian literature. Ancient Ethiopian literature starts with Axumite texts written in the Geʽez language using the Geʽez script, indigenous to both Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Afghan literature or literature of Afghanistan refers to the literature produced in the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Influenced by Central and South Asian literature, it is predominantly written in two native and official languages of Afghanistan, Dari and Pashto. Some regional languages such as Uzbek, Turkmen, Balochi, and Pashayi also appears in Afghan literature. While Afghanistan is a multilingual country, these languages are generally used as oral compositions and written texts by the Afghan writers and in Afghan curriculum. Its literature is highly influenced by Persian and Arabic literature in addition to Central and South Asia.

Efik literature is literature spoken or written in the Efik language, particularly by Efik people or speakers of the Efik language. Traditional Efik literature can be classified as follows; Ase, Uto, Mbụk, Ñke and Ikwọ. Other aspects of Efik literature include prose and drama (Mbre).

Igbo literature encompasses both oral and written works of fiction and nonfiction created by the Igbo people in the Igbo language. This literary tradition reflects the cultural heritage, history, and linguistic diversity of the Igbo community. The roots of Igbo literature trace back to ancient oral traditions that included chants, folk songs, narrative poetry, and storytelling. These oral narratives were frequently recited during rituals, childbirth ceremonies, and gatherings. Proverbs and riddles were also used to convey wisdom and entertain children.