Amenemhat III, also known as Amenemhet III, was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the sixth king of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. He was elevated to throne as co-regent by his father Senusret III, with whom he shared the throne as the active king for twenty years. During his reign, Egypt attained its cultural and economic zenith of the Middle Kingdom.

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt is the period in the history of ancient Egypt following a period of political division known as the First Intermediate Period. The Middle Kingdom lasted from approximately 2040 to 1782 BC, stretching from the reunification of Egypt under the reign of Mentuhotep II in the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty. The kings of the Eleventh Dynasty ruled from Thebes and the kings of the Twelfth Dynasty ruled from el-Lisht.

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt is a series of rulers reigning from 1991–1802 BC, at what is often considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom. The dynasty periodically expanded its territory from the Nile delta and valley South beyond the second cataract and East into Canaan.

Amenemhat I, also known as Amenemhet I, was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the first king of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom.

Nubkaure Amenemhat II, also known as Amenemhet II, was the third pharaoh of the 12th Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Although he ruled for at least 35 years, his reign is rather obscure, as well as his family relationships.

Senusret I also anglicized as Sesostris I and Senwosret I, was the second pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1971 BC to 1926 BC, and was one of the most powerful kings of this Dynasty. He was the son of Amenemhat I. Senusret I was known by his prenomen, Kheperkare, which means "the Ka of Re is created." He expanded the territory of Egypt allowing him to rule over an age of prosperity.

Senusret II or Sesostris II was the fourth pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1897 BC to 1878 BC. His pyramid was constructed at El-Lahun. Senusret II took a great deal of interest in the Faiyum oasis region and began work on an extensive irrigation system from Bahr Yussef through to Lake Moeris through the construction of a dike at El-Lahun and the addition of a network of drainage canals. The purpose of his project was to increase the amount of cultivable land in that area. The importance of this project is emphasized by Senusret II's decision to move the royal necropolis from Dahshur to El-Lahun where he built his pyramid. This location would remain the political capital for the 12th and 13th Dynasties of Egypt. Senusret II was known by his prenomen Khakheperre, which means "The Ka of Re comes into being". The king also established the first known workers' quarter in the nearby town of Senusrethotep (Kahun).

Khakaure Senusret III was a pharaoh of Egypt. He ruled from 1878 BC to 1839 BC during a time of great power and prosperity, and was the fifth king of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. He was a great pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty and is considered to rule at the height of the Middle Kingdom. Consequently, he is regarded as one of the sources for the legend about Sesostris. His military campaigns gave rise to an era of peace and economic prosperity that reduced the power of regional rulers and led to a revival in craftwork, trade, and urban development. Senusret III was among the few Egyptian kings who were deified and honored with a cult during their own lifetime.

El Lahun. It was known as Ptolemais Hormos in Ptolemaic Egypt.

Hawara is an archaeological site of Ancient Egypt, south of the site of Crocodilopolis at the entrance to the depression of the Fayyum oasis. It is the site of a pyramid built by Pharaoh Amenemhat III, who was a Pharaoh of the 12th dynasty of the Old Kingdom, in 19 century B.C.

Herbert Eustis Winlock was an American Egyptologist and archaeologist, employed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for his entire career. Between 1906 and 1931 he took part in excavations at El-Lisht, Kharga Oasis and around Luxor, before serving as director of the Metropolitan Museum from 1932 to 1939.

The pyramid of Amenemhat I is an Egyptian burial structure built at Lisht by the founder of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt, Amenemhat I.

The pyramid of Senusret I is an Egyptian pyramid built to be the burial place of the Pharaoh Senusret I. The pyramid was built during the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt at el-Lisht, near the pyramid of his father, Amenemhat I. Its ancient name was Senusret Petei Tawi.

Sithathoriunet was an Ancient Egyptian king's daughter of the 12th Dynasty, mainly known from her burial at El-Lahun in which a treasure trove of jewellery was found. She was possibly a daughter of Senusret II since her burial site was found next to the pyramid of this king. If so, this would make her one of five known children and one of three daughters of Senusret II—the other children were Senusret III, Senusretseneb, Itakayt and Nofret.

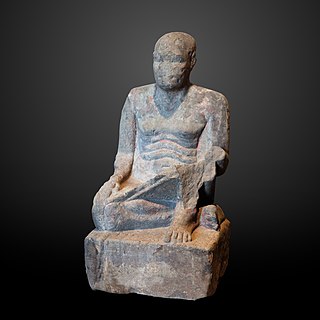

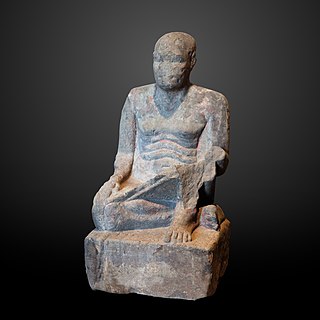

Mentuhotep was an ancient Egyptian official and treasurer under the 12th Dynasty pharaoh Senusret I. Mentuhotep is one of the best attested officials of the Middle Kingdom period. There is a series of statues found at Karnak, showing him as a scribe. On these he has been given the title of overseer of all royal works, which would suggest that he was involved in overseeing the construction of the temple at Karnak. At el-Lisht he had a large tomb next to the pyramid of Senusret I. When it was found it was badly damaged, but there are remains of high quality reliefs and fragments of statues. The burial chamber still contained two sarcophagi, one smashed and the other one well preserved, made of granite and with brightly painted interiors.

Siese was a vizier and treasurer of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He was most likely in office under Senusret III.

Several ancient Egyptian solar ships and boat pits were found in many ancient Egyptian sites. The most famous is the Khufu ship, which is now preserved in the Grand Egyptian Museum. The full-sized ships or boats were buried near ancient Egyptian pyramids or temples at many sites. The history and function of the ships are not precisely known. They are most commonly created as a "solar barge", a ritual vessel to carry the resurrected king with the sun god Ra across the heavens. This is a common theme in the Pyramid Texts, and these buried boats might be a real-life equivalent of solar barges. Similarly, another explanation behind these boats is that they were built for past kings to carry them to the afterlife. Because of these ships' association with the sun, they are often found in an east-west orientation in order to follow the path of the sun.

The pyramid of Senusret III is an ancient Egyptian pyramid located at Dahshur and built for pharaoh Senusret III of the 12th Dynasty.

Senebtisi was an ancient Egyptian woman who lived at the end of the 12th Dynasty, around 1800 BC. She is only known from her undisturbed burial found at Lisht.

El Ayyat is a city in the Giza Governorate, Egypt. Its population was estimated at 44,000 people in 2018.