Related Research Articles

Jurisprudence is the philosophy and theory of law. It is concerned primarily with what the law is and what it ought to be. That includes questions of how persons and social relations are understood in legal terms, and of the values in and of law. Work that is counted as jurisprudence is mostly philosophical, but it includes work that also belongs to other disciplines, such as sociology, history, politics and economics.

Natural law is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law. According to the theory of law called jusnaturalism, all people have inherent rights, conferred not by act of legislation but by "God, nature, or reason." Natural law theory can also refer to "theories of ethics, theories of politics, theories of civil law, and theories of religious morality."

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, liberty, justice, property, rights, law, and the enforcement of laws by authority: what they are, if they are needed, what makes a government legitimate, what rights and freedoms it should protect, what form it should take, what the law is, and what duties citizens owe to a legitimate government, if any, and when it may be legitimately overthrown, if ever.

Usury is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is charged in excess of the maximum rate that is allowed by law. A loan may be considered usurious because of excessive or abusive interest rates or other factors defined by the laws of a state. Someone who practices usury can be called a usurer, but in modern colloquial English may be called a loan shark.

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

The Euthyphro dilemma is found in Plato's dialogue Euthyphro, in which Socrates asks Euthyphro, "Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" (10a)

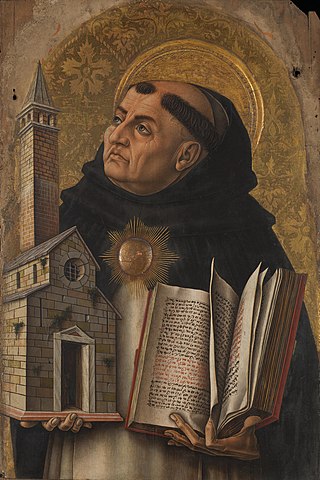

Thomism is the philosophical and theological school which arose as a legacy of the work and thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the Dominican philosopher, theologian, and Doctor of the Church.

Francisco Suárez, was a Spanish Jesuit priest, philosopher and theologian, one of the leading figures of the School of Salamanca movement, and generally regarded among the greatest scholastics after Thomas Aquinas. His work is considered a turning point in the history of second scholasticism, marking the transition from its Renaissance to its Baroque phases. According to Christopher Shields and Daniel Schwartz, "figures as distinct from one another in place, time, and philosophical orientation as Leibniz, Grotius, Pufendorf, Schopenhauer and Heidegger, all found reason to cite him as a source of inspiration and influence."

Thomas Cajetan, also known as Gaetanus, commonly Tommaso de Vio or Thomas de Vio, was an Italian philosopher, theologian, cardinal and the Master of the Order of Preachers 1508 to 1518. He was a leading theologian of his day who is now best known as the spokesman for Catholic opposition to the teachings of Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation while he was the Pope's Legate in Augsburg, and among Catholics for his extensive commentary on the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas.

Positive laws are human-made laws that oblige or specify an action. Positive law also describes the establishment of specific rights for an individual or group. Etymologically, the name derives from the verb to posit.

John Mitchell Finnis,, is an Australian legal philosopher and jurist specializing in jurisprudence and the philosophy of law. He is an original interpreter of Aristotle and Aquinas, and counts Germain Grisez as a major influence and collaborator. He has made contributions to the philosophy of knowledge, metaphysics, and moral philosophy.

The Summa Theologiae or Summa Theologica, often referred to simply as the Summa, is the best-known work of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a scholastic theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is a compendium of all of the main theological teachings of the Catholic Church, intended to be an instructional guide for theology students, including seminarians and the literate laity. Presenting the reasoning for almost all points of Christian theology in the West, topics of the Summa follow the following cycle: God; Creation, Man; Man's purpose; Christ; the Sacraments; and back to God.

Thomas Aquinas, OP was an Italian Dominican friar and priest, an influential philosopher and theologian, and a jurist in the tradition of scholasticism from the county of Aquino in the Kingdom of Sicily, Italy; he is known within the tradition as the Doctor Angelicus, the Doctor Communis, and the Doctor Universalis. In 1999, John Paul II added a new title to these traditional ones: Doctor Humanitatis.

Communitas perfecta or societas perfecta is the Latin name given to one of several ecclesiological, canonical, and political theories of the Catholic Church. The doctrine teaches that the church is a self-sufficient or independent group which already has all the necessary resources and conditions to achieve its overall goal of the universal salvation of mankind. It has historically been used in order to define church–state relations and to provide a theoretical basis for the legislative powers of the church in the philosophy of Catholic canon law.

An unjust law is no law at all, in Latin lex iniusta non est lex, is an expression of natural law, acknowledging that authority is not legitimate unless it is good and right. It has become a standard legal maxim around the world.

The Augustinian theodicy, named for the 4th- and 5th-century theologian and philosopher Augustine of Hippo, is a type of Christian theodicy that developed in response to the evidential problem of evil. As such, it attempts to explain the probability of an omnipotent (all-powerful) and omnibenevolent (all-loving) God amid evidence of evil in the world. A number of variations of this kind of theodicy have been proposed throughout history; their similarities were first described by the 20th-century philosopher John Hick, who classified them as "Augustinian". They typically assert that God is perfectly (ideally) good, that he created the world out of nothing, and that evil is the result of humanity's original sin. The entry of evil into the world is generally explained as consequence of original sin and its continued presence due to humans' misuse of free will and concupiscence. God's goodness and benevolence, according to the Augustinian theodicy, remain perfect and without responsibility for evil or suffering.

Treatise on Law is Thomas Aquinas' major work of legal philosophy. It forms questions 90–108 of the Prima Secundæ of the Summa Theologiæ, Aquinas' masterwork of Scholastic philosophical theology. Along with Aristotelianism, it forms the basis for the legal theory of Catholic canon law.

A determinatio is an authoritative determination by the legislator concerning the application of practical principles, that is not necessitated by deduction from natural or divine law but is based on the contingencies of practical judgement within the possibilities allowed by reason. The concept derives from the legal philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, and continues to be a part of discussions in natural law theory.

The philosophy, theology, and fundamental theory of Catholic canon law are the fields of philosophical, theological (ecclesiological), and legal scholarship which concern the place of canon law in the nature of the Catholic Church, both as a natural and as a supernatural entity. Philosophy and theology shape the concepts and self-understanding of canon law as the law of both a human organization and as a supernatural entity, since the Catholic Church believes that Jesus Christ instituted the church by direct divine command, while the fundamental theory of canon law is a meta-discipline of the "triple relationship between theology, philosophy, and canon law".

Jusnaturalism or iusnaturalism is a theory of law, which holds that legal norms follow a human universal knowledge on justice and harmony of relations. Thus, it views enacted laws that contradict such universal knowledge as unjust and illegitimate. Modern theorists considered as iusnaturalists include Hugo Grotius, Immanuel Kant, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and Franz von Zeiller, among others.

References

Notes

- 1 2 Mohnhaupt 2008, p. 75–76.

- ↑ Aspell 1999, p. 198–200.

- 1 2 Grant 2003, p. 200.

- ↑ Flannery 2001, p. 73.

- ↑ Voegelin 1997, p. 227–228.

- ↑ "SCG (Hanover House edn 1955-57) bk 3, ch 125(10)". Archived from the original on 2017-12-11. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- ↑ SCG (Hanover House edn 1955-57) bk 4, ch 34(17) Archived 2018-02-20 at the Wayback Machine .

- ↑ Heckel, Heckel & Krodel 2010, pp. 45, 51, 285.

- ↑ Voegelin 1997, p. 224,227–228.

- 1 2 Sharma & Sharma 2006, p. 312.

- ↑ Grewe 2000, p. 84.

- ↑ Skinner 1978, p. 148.

- ↑ Willke 2007, p. 101.

- ↑ Gönenç 2002, p. 83–85.

- ↑ Betz 2008, p. 105.

- ↑ Villanova 2005, p. 5.

- ↑ Khaddūrī 2002, p. 8.

Sources used

- Aspell, Patrick J. (1999). Medieval western philosophy: the European emergence. Cultural heritage and contemporary change: Culture and values. Vol. 9. CRVP. ISBN 978-1-56518-094-9.

- Betz, Joseph (2008). "Civil Disobedience". In Lachs, John; Talisse, Robert B. (eds.). American philosophy: an encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93926-3.

- Flannery, Kevin L. (2001). Acts Amid Precepts: The Logical Structure of Thomas Aquinas's Moral Theology. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-08815-4.

- Khaddūrī, Majīd (2002). The Islamic Law of Nations: Shaybani's Siyar. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6975-4.

- Gönenç, Levent (2002). "Political Culture". Law in Eastern Europe. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-411-1836-3.

- Grant, Moyra (2003). Key Ideas in Politics . Nelson Thornes. ISBN 978-0-7487-7096-0.

- Grewe, Wilhelm Georg (2000). Byers, Michael (ed.). The epochs of international law. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-015339-2.

- Heckel, Johannes; Heckel, Martin; Krodel, Gottfried G. (2010). "The Divine Positive Law". Lex charitatis: a juristic disquisition on law in the theology of Martin Luther . Emory University studies in law and religion. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6445-1.

- Mohnhaupt, Heinz (2008). ""Lex certa" and "ius certum": The Search for Legal Certainty and Security". In Daston, Lorraine; Stolleis, Michael (eds.). Natural law and laws of nature in early modern Europe: jurisprudence, theology, moral and natural philosophy. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-5761-3.

- Sharma, Urmila; Sharma, S.K. (2006). Western Political Thought. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-683-9.

- Skinner, Quentin (1978). The Foundations of Modern Political Thought: The Age of Reformation. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29435-5.

- Villanova, Ron (2005). Legal Methods: A Guide for Paralegals and Law Students. Llumina Press. ISBN 978-1-59526-257-8.

- Voegelin, Eric (1997). "Saint Thomas Aquinas". In Sandoz, Ellis (ed.). The collected works of Eric Voegelin. History of Political Ideas. Vol. 2. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1142-2.

- Willke, Helmut (2007). Smart governance: governing the global knowledge society. Campus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-593-38253-1.

- Thomas Aquinas. Summa Theologica .

- Thomas Aquinas. Summa contra Gentiles .

- King, Martin Luther (16 April 1963). "Letter from Birmingham Jail".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)