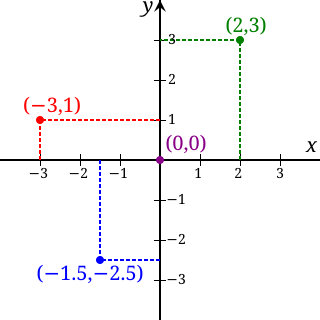

In mathematics, the absolute value or modulus of a real number , denoted , is the non-negative value of without regard to its sign. Namely, if x is a positive number, and if is negative, and . For example, the absolute value of 3 is 3, and the absolute value of −3 is also 3. The absolute value of a number may be thought of as its distance from zero.

In mathematics, more specifically in functional analysis, a Banach space is a complete normed vector space. Thus, a Banach space is a vector space with a metric that allows the computation of vector length and distance between vectors and is complete in the sense that a Cauchy sequence of vectors always converges to a well defined limit that is within the space.

In mathematical analysis, a metric space M is called complete if every Cauchy sequence of points in M has a limit that is also in M.

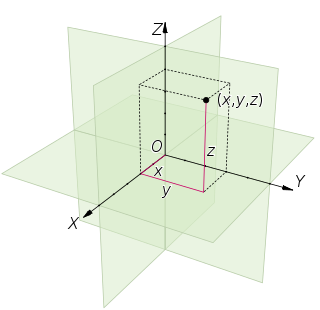

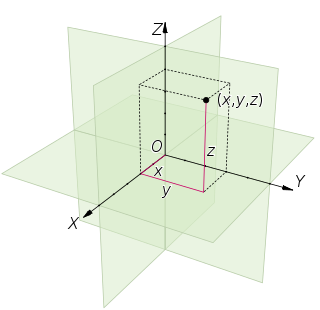

Euclidean space is the fundamental space of geometry, intended to represent physical space. Originally, that is, in Euclid's Elements, it was the three-dimensional space of Euclidean geometry, but in modern mathematics there are Euclidean spaces of any positive integer dimension, including the three-dimensional space and the Euclidean plane. The qualifier "Euclidean" is used to distinguish Euclidean spaces from other spaces that were later considered in physics and modern mathematics.

In mathematics, a metric space is a set together with a notion of distance between its elements, usually called points. The distance is measured by a function called a metric or distance function. Metric spaces are the most general setting for studying many of the concepts of mathematical analysis and geometry.

In mathematics, a normed vector space or normed space is a vector space over the real or complex numbers, on which a norm is defined. A norm is the formalization and the generalization to real vector spaces of the intuitive notion of "length" in the real (physical) world. A norm is a real-valued function defined on the vector space that is commonly denoted and has the following properties:

- It is nonnegative, meaning that for every vector

- It is positive on nonzero vectors, that is,

- For every vector and every scalar

- The triangle inequality holds; that is, for every vectors and

In mathematics, a topological space is, roughly speaking, a geometrical space in which closeness is defined but cannot necessarily be measured by a numeric distance. More specifically, a topological space is a set whose elements are called points, along with an additional structure called a topology that can be defined as a set of neighbourhoods for each point, that satisfy some axioms formalizing the concept of closeness. There are several equivalent definitions of a topology, the most commonly used is the definition through open sets, which is easier to manipulate.

In the mathematical field of topology, a uniform space is a set with a uniform structure. Uniform spaces are topological spaces with additional structure that is used to define uniform properties such as completeness, uniform continuity and uniform convergence. Uniform spaces generalize metric spaces and topological groups, but the concept is designed to formulate the weakest axioms needed for most proofs in analysis.

In mathematics, a topological vector space is one of the basic structures investigated in functional analysis. A topological vector space is a vector space that is also a topological space with the property that the vector space operations are also continuous functions. Such a topology is called a vector topology and every topological vector space has a uniform topological structure, allowing a notion of uniform convergence and completeness. Some authors also require that the space is a Hausdorff space. One of the most widely studied categories of TVSs are locally convex topological vector spaces. This article focuses on TVSs that are not necessarily locally convex. Banach spaces, Hilbert spaces and Sobolev spaces are other well-known examples of TVSs.

In mathematics, a pseudometric space is a generalization of a metric space in which the distance between two distinct points can be zero. Pseudometric spaces were introduced by Đuro Kurepa in 1934. In the same way as every normed space is a metric space, every seminormed space is a pseudometric space. Because of this analogy the term semimetric space is sometimes used as a synonym, especially in functional analysis.

In functional analysis and related areas of mathematics, Fréchet spaces, named after Maurice Fréchet, are special topological vector spaces. They are generalizations of Banach spaces. All Banach and Hilbert spaces are Fréchet spaces. Spaces of infinitely differentiable functions are typical examples of Fréchet spaces, many of which are typically not Banach spaces.

In mathematics, particularly in functional analysis, a seminorm is a vector space norm that need not be positive definite. Seminorms are intimately connected with convex sets: every seminorm is the Minkowski functional of some absorbing disk and, conversely, the Minkowski functional of any such set is a seminorm.

In functional analysis and related areas of mathematics, locally convex topological vector spaces (LCTVS) or locally convex spaces are examples of topological vector spaces (TVS) that generalize normed spaces. They can be defined as topological vector spaces whose topology is generated by translations of balanced, absorbent, convex sets. Alternatively they can be defined as a vector space with a family of seminorms, and a topology can be defined in terms of that family. Although in general such spaces are not necessarily normable, the existence of a convex local base for the zero vector is strong enough for the Hahn–Banach theorem to hold, yielding a sufficiently rich theory of continuous linear functionals.

In mathematics, a norm is a function from a real or complex vector space to the non-negative real numbers that behaves in certain ways like the distance from the origin: it commutes with scaling, obeys a form of the triangle inequality, and is zero only at the origin. In particular, the Euclidean distance of a vector from the origin is a norm, called the Euclidean norm, or 2-norm, which may also be defined as the square root of the inner product of a vector with itself.

In mathematics, the real coordinate space of dimension n, denoted Rn or , is the set of the n-tuples of real numbers, that is the set of all sequences of n real numbers. With component-wise addition and scalar multiplication, it is a real vector space, and its elements are called coordinate vectors.

In mathematics, a manifold is a topological space that locally resembles Euclidean space near each point. More precisely, an n-dimensional manifold, or n-manifold for short, is a topological space with the property that each point has a neighborhood that is homeomorphic to an open subset of n-dimensional Euclidean space.

In Riemannian geometry, the filling radius of a Riemannian manifold X is a metric invariant of X. It was originally introduced in 1983 by Mikhail Gromov, who used it to prove his systolic inequality for essential manifolds, vastly generalizing Loewner's torus inequality and Pu's inequality for the real projective plane, and creating systolic geometry in its modern form.

In functional analysis and related areas of mathematics, a complete topological vector space is a topological vector space (TVS) with the property that whenever points get progressively closer to each other, then there exists some point towards which they all get closer. The notion of "points that get progressively closer" is made rigorous by Cauchy nets or Cauchy filters, which are generalizations of Cauchy sequences, while "point towards which they all get closer" means that this Cauchy net or filter converges to The notion of completeness for TVSs uses the theory of uniform spaces as a framework to generalize the notion of completeness for metric spaces. But unlike metric-completeness, TVS-completeness does not depend on any metric and is defined for all TVSs, including those that are not metrizable or Hausdorff.

In mathematics, and especially differential and algebraic geometry, K-stability is an algebro-geometric stability condition, for complex manifolds and complex algebraic varieties. The notion of K-stability was first introduced by Gang Tian and reformulated more algebraically later by Simon Donaldson. The definition was inspired by a comparison to geometric invariant theory (GIT) stability. In the special case of Fano varieties, K-stability precisely characterises the existence of Kähler–Einstein metrics. More generally, on any compact complex manifold, K-stability is conjectured to be equivalent to the existence of constant scalar curvature Kähler metrics.

In functional analysis and related areas of mathematics, a metrizable topological vector space (TVS) is a TVS whose topology is induced by a metric. An LM-space is an inductive limit of a sequence of locally convex metrizable TVS.

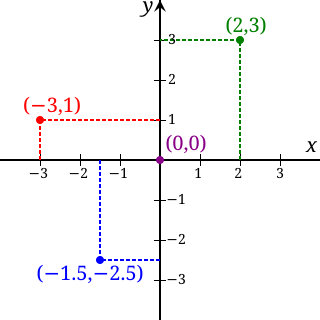

![An illustration comparing the taxicab metric to the Euclidean metric on the plane: According to the taxicab metric the red, yellow, and blue paths have the same length (12). According to the Euclidean metric, the green path has length

6

2

[?]

8.49

{\displaystyle 6{\sqrt {2}}\approx 8.49}

, and is the unique shortest path. Manhattan distance.svg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Manhattan_distance.svg/200px-Manhattan_distance.svg.png)