The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was the ruling dynasty of China from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last imperial dynasty of China ruled by Han Chinese. Although the primary capital of Beijing fell in 1644 to a rebellion led by Li Zicheng, numerous rump regimes ruled by remnants of the Ming imperial family—collectively called the Southern Ming—survived until 1662.

The Miao are a group of linguistically-related peoples living in Southern China and Southeast Asia, which are recognized by the government of China as one of the 56 official ethnic groups. The Miao live primarily in southern China's mountains, in the provinces of Guizhou, Yunnan, Sichuan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangxi, Guangdong and Hainan. Some sub-groups of the Miao, most notably the Hmong people, have migrated out of China into Southeast Asia. Following the communist takeover of Laos in 1975, a large group of Hmong refugees resettled in several Western nations, mainly in the United States, France and Australia.

The Revolt of the Three Feudatories, also known as the Rebellion of Wu Sangui, was a rebellion in China lasting from 1673 to 1681, during the early reign of the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). The revolt was led by the three lords of the fiefdoms in Yunnan, Guangdong and Fujian provinces against the Qing central government. These hereditary titles had been given to prominent Han Chinese defectors who had helped the Manchu conquer China during the transition from Ming to Qing. The feudatories were supported by Zheng Jing's Kingdom of Tungning in Taiwan, which sent forces to invade Mainland China. Additionally, minor Han military figures, such as Wang Fuchen and the Chahar Mongols, also revolted against Qing rule. After the last remaining Han resistance had been put down, the former princely titles were abolished.

Taoyuan County is under the administration of Changde, Hunan Province, China. The Yuan River, a tributary of the Yangtze, flows through Taoyuan. It covers an area of 4441 square kilometers, of which 895 km2 (346 sq mi) is arable land. It is 229 km (142 mi) from Zhangjiang Town, the county seat, to Changsha, the capital city of Hunan province. The county occupies the southwestern corner of Changde City and borders the prefecture-level cities of Zhangjiajie to the northwest and Huaihua to the southwest.

Zongdu, usually translated as Viceroy, Head of State or Governor-General, governed one territory or more provinces of China during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Semu is the name of a caste established by the Yuan dynasty. The Semu categories refers to people who come from Central and West Asia, it is told that there are 31 categories among them. They had come to serve the Yuan dynasty by enfranchising under the dominant Mongol caste. The Semu were not a self-defined and homogeneous ethnic group per se, but one of the four castes of the Yuan dynasty: the Mongols, Semu, the "Han" and the Southerners. Among the Semu were Buddhist Turpan Uyghurs, Tanguts and Tibetans; Nestorian Christian tribes like the Ongud; Alans; Muslim Central Asian Persian and Turkic peoples including the Khwarazmians and Karakhanids; West Asian Arab, Jewish, Christians and other minor groups who are from even further west.

The Southern Ming, or less commonly the Later Ming, officially the Great Ming, was a series of dynastic rump states headed by the imperial members of the Ming dynasty in southern China following the fall of Beijing in 1644. Shun forces led by Li Zicheng captured Beijing and the Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide. The Ming general Wu Sangui then opened the gates of the Shanhai Pass in the eastern section of the Great Wall to the Qing banners, in hope of using them to annihilate the Shun forces. Ming loyalists fled to Nanjing, where they enthroned Zhu Yousong as the Hongguang Emperor, marking the start of the Southern Ming. The Nanjing regime lasted until 1645, when Qing forces captured Nanjing, and by then Zhu had been executed. Later figures continued to hold court in various southern Chinese cities, although the Qing considered them to be pretenders.

Li Dingguo was a military general who fought for the Southern Ming against the Qing Dynasty.

The Battle of Kherlen was a battle between the Northern Yuan dynasty of Mongolia and Ming China that took place at the banks of Kherlen River (Kerulen) in the Mongolian Plateau on 23 September 1409.

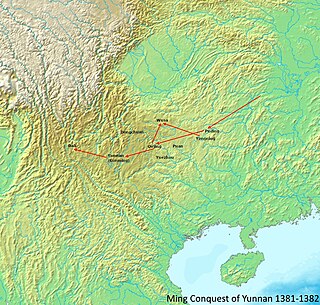

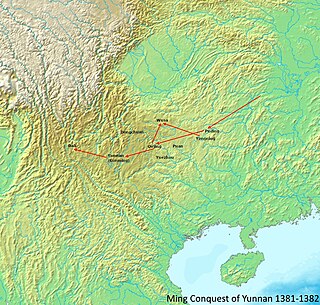

The Ming conquest of Yunnan was the final phase in the Ming dynasty expulsion of Mongol-led Yuan dynasty rule from China proper in the 1380s.

The Hmongic also known as Miao languages include the various languages spoken by the Miao people, Pa-Hng, and the "Bunu" languages used by non-Mien-speaking Yao people.

The Miao Rebellion of 1795–1806 was an anti-Qing uprising in Hunan and Guizhou provinces, during the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor. It was catalyzed by tensions between local populations and Han Chinese immigrants. Bloodily suppressed, it served as the antecedent to the much larger uprising of Miao Rebellion (1854–73).

The Miao Rebellion of 1735–1736 was an uprising of autochthonous people from southwest China.

The Miao rebellion of 1854–1873, also known as the Qian rebellion was an uprising of ethnic Miao and other groups in Guizhou province during the reign of the Qing dynasty. Despite its name, Robert Jenks estimates that ethnic Miao made up less than half of the uprising's participants. The uprising was preceded by Miao rebellions in 1735–36 and 1795–1806, and was one of many ethnic uprisings sweeping China in the 19th century. The rebellion spanned the Xianfeng and Tongzhi periods of the Qing dynasty, and was eventually suppressed with military force. Estimates place the number of casualties as high as 4.9 million out of a total population of 7 million, though these figures are likely overstated.

The Prince of Anhua rebellion or Prince Anhua uprising was a rebellion by Zhu Zhifan, Prince of Anhua and member of the Zhu royal family, against the reign of the Zhengde Emperor from 12 May 1510 to 30 May 1510. The Prince of Anhua revolt was one of two princedom rebellions during Zhengde's rule as emperor of the Ming dynasty, and precedes the Prince of Ning rebellion in 1519.

Hala Bashi was a Uyghur Muslim general of the Ming dynasty and its Hongwu Emperor.

Eastern Depot or Eastern Bureau was a Ming dynasty spy and secret police agency run by eunuchs. It was created by the Yongle Emperor.

A eunuch is a man who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The Bozhou rebellion was a Miao uprising that occurred in Guizhou and spread to Sichuan and Huguang between 1589 and 1600 during the Ming dynasty.

Events from the year 1662 in China.