Zheng He was a Chinese admiral, explorer, diplomat, and bureaucrat during the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644). He is often regarded as the greatest admiral in Chinese history. Born into a Muslim family as Ma He, he later adopted the surname Zheng conferred onto him by the Yongle Emperor. Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng commanded seven treasure voyages across Asia under the commission of the Yongle Emperor and the succeeding Xuande Emperor. According to legend, Zheng's largest ships were almost twice as long as any wooden ship ever recorded, and carried hundreds of sailors on four decks.

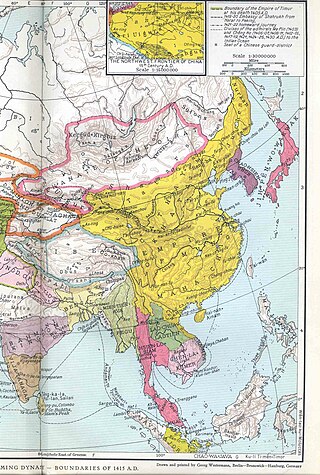

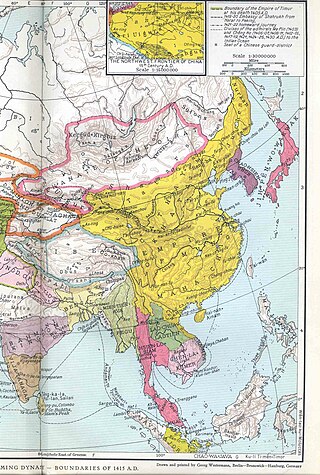

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last imperial dynasty of China ruled by the Han people, the majority ethnic group in China. Although the primary capital of Beijing fell in 1644 to a rebellion led by Li Zicheng, numerous rump regimes ruled by remnants of the Ming imperial family—collectively called the Southern Ming—survived until 1662.

The Yongle Emperor, personal name Zhu Di, was the third emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 1424.

Hongwu Emperor, also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizu of Ming (明太祖), personal name Zhu Yuanzhang, courtesy name Guorui, was the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1368 to 1398.

The Xuande Emperor, also known by his temple name as the Emperor Xuanzong of Ming (明宣宗), personal name Zhu Zhanji (朱瞻基), was the fifth emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1425 to 1435. He was the son and successor of the Hongxi Emperor. "Xuande", the era name of his reign, means "proclamation of virtue".

The Jianwen Emperor, personal name Zhu Yunwen (朱允炆), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Huizong of Ming (明惠宗) and by his posthumous name as the Emperor Hui of Ming (明惠帝), was the second emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1398 to 1402. Zhu Yunwen's father was Zhu Biao, the eldest son and crown prince of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dynasty. Zhu Biao died at the age of 37 in 1392, after which the Hongwu Emperor named Zhu Yunwen as his successor. He ascended the throne after the Hongwu Emperor's death in June 1398.

The Hồ dynasty, officially Great Ngu, was a short-lived Vietnamese dynasty consisting of the reigns of two monarchs, Hồ Quý Ly and his second son, Hồ Hán Thương. The practice of bequeathing the throne to a designated son was similar to what had happened in the previous Trần dynasty and was meant to avoid sibling rivalry. Hồ Quý Ly's eldest son, Hồ Nguyên Trừng, played his part as the dynasty's military general. In 2011, UNESCO declared the Citadel of the Hồ Dynasty in Thanh Hóa Province a world heritage site. The Hồ dynasty was conquered by the Chinese Ming dynasty in 1407.

The Later Trần dynasty, officially Great Việt, was a Vietnamese dynasty. It was the continuous line of the Tran dynasty that led Vietnamese rebellions against the Chinese Ming dynasty from between 1407 and 1413. The regime was characterized by two revolts against the Ming China which had by then established its rule over Vietnam.

The Fourth Era of Northern Domination was a period of Vietnamese history, from 1407 to 1427, during which Ming-dynasty China ruled Vietnam as the province of Jiaozhi. The Ming established their rule in Vietnam following their conquest of the Hồ dynasty in 1406-1407. The fourth period of Chinese rule over Vietnam eventually ended with the establishment of the Lê dynasty in 1428.

The Baiyi Zhuan is a description of the Dai polity of Mong Mao in 1396 written by two envoys, Qian Guxun and Li Sicong, sent by the Ming court in China to resolve conflicts between the Ava Kingdom in Burma and Mong Mao, also known as Luchuan-Pingmian. The description includes the history, geography, political and social organization, customs, music, food, and products of the region. Ming Shilu describes the work:

The Messengers Li Si-cong and Qian Gu-xun were sent as envoys to the country of Burma and to the Bai-yi [Tai]...When Si-cong and the others returned, they memorialized the events. They also wrote Account of the Bai-yi, which recorded in detail the area's mountains and rivers, the people, the customs and the roads, and presented it. The Emperor was impressed that they had not neglected the duties of envoys and said that their talents were useful. He was very pleased and conferred upon each of them a set of clothing.

Four major military campaigns were launched by the Mongol Empire, and later the Yuan dynasty, against the kingdom of Đại Việt ruled by the Trần dynasty and the kingdom of Champa in 1258, 1282–1284, 1285, and 1287–88. The campaigns are treated by a number of scholars as a success due to the establishment of tributary relations with Đại Việt despite the Mongols suffering major military defeats. In contrast, modern Vietnamese historiography regards the war as a major victory against the foreign invaders.

Đại Việt, was a Vietnamese monarchy in eastern Mainland Southeast Asia from the 10th century AD to the early 19th century, centered around the region of present-day Hanoi, Northern Vietnam. Its early name, Đại Cồ Việt, was established in 968 by Vietnamese ruler Đinh Bộ Lĩnh after he ended the Anarchy of the 12 Warlords, until the beginning of the reign of Lý Thánh Tông, the third emperor of the Lý dynasty. Đại Việt lasted until the reign of Gia Long, the first emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty, when the name was changed to Việt Nam in 1804. Under rule of bilateral diplomacy with Imperial China, it was known as Principality of Giao Chỉ (975–1164) and Kingdom of Annam (1164–1804) when Emperor Xiaozong of Song upgraded Đại Việt's status from Principality to Kingdom.

Hồ Quý Ly ruled Đại Ngu (Vietnam) from 1400 to 1401 as the founding emperor of the short-lived Hồ dynasty. Quý Ly rose from a post as an official served the court of the ruling Trần dynasty and a military general fought against the Cham forces during the Cham–Vietnamese War (1367–1390). After his military defeat in the Ming Conquest of Dai Ngu (1406–1407), he and his son were captured as prisoners and were exiled to China, while the Dai Viet Empire became the thirteenth province of Ming Empire.

The Ming invasion of Viet, known in Vietnam as the Ming–Đại Ngu War was a military campaign against the kingdom of Đại Ngu under the Hồ dynasty by the Ming dynasty of China. The campaign began with Ming intervention in support of a rival faction to the Hồ dynasty which ruled Đại Ngu, but ended with the incorporation of Đại Ngu into the Ming dynasty as the province of Jiaozhi. The invasion is acknowledged by recent historians as one of the most important wars of the late medieval period, whereas both sides, especially the Ming, used the most advanced weapons in the world at the time.

The Lam Sơn uprising was a Vietnamese rebellion led by Lê Lợi in the province of Jiaozhi from 1418 to 1427 against the rule of Ming China. The success of the rebellion led to the establishment of the Later Lê dynasty by Lê Lợi in Đại Việt.

The Đại Việt–Lan Xang War of 1479–84, also known as the White Elephant War, was a military conflict precipitated by the invasion of the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang by the Vietnamese Đại Việt Empire. The Vietnamese invasion was a continuation of Emperor Lê Thánh Tông's expansion, by which Đại Việt had conquered the kingdom of Champa in 1471. The conflict grew into a wider conflagration involving the Ai-Lao people from Sip Song Chau Tai along with the Mekong river valley Tai peoples from the Yuan kingdom of Lan Na, Lü kingdom Sip Song Pan Na, to Muang along the upper Irawaddy river. The conflict ultimately lasted approximately five years growing to threatened the southern border of Yunnan and raising the concerns of Ming China. Early gunpowder weapons played a major role in the conflict, enabling Đại Việt's aggression. Early success in the war allowed Đại Việt to capture the Lao capital of Luang Prabang and destroy the Muang Phuan city of Xiang Khouang. The war ended as a strategic victory for Lan Xang, as they were able to force the Vietnamese to withdraw with the assistance of Lan Na and Ming China. Ultimately the war contributed to closer political and economic ties between Lan Na, Lan Xang, and Ming China. In particular, Lan Na's political and economic expansion led to a "golden age" for that kingdom.

Trần Thiêm Bình was a pretender to the Vietnamese throne during Hồ dynasty. He was mentioned as Chen Tian-ping (陳天平) in Chinese records.

The Champa–Đại Việt War (1367–1390) was a costly military confrontation fought between the Đại Việt kingdom under the ruling Trần dynasty and the kingdom of Champa led by the King of Chế Bồng Nga in the late 14th century, from 1367 to 1390. By 1330s, Đại Việt and Khmer Empire both felt into swiftly declining due to climate changes, population expansion, widespread bubonic plague, famines and many other factions, which contributed to Champa's resurgence of the 14th century. In 1360, Chế Bồng Nga, son of king Chế A Nan was enthroned as king of Champa, reunited the Chams under his banner, and in 1367 he demanded Trần Dụ Tông the return of two former provinces Ô and Lý to Champa. Declined to this demand, Trần Dụ Tông sent an army to strike Champa but was repulsed.

The Ming-Đại Việt War of 1406–1428 was a conflict between the Ming dynasty of China and Vietnam. The Ming dynasty's objective was to annex Vietnam, and while they initially had some success, the Vietnamese ultimately defended their independence.