Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, commonly known as NDG, is a residential neighbourhood of Montreal in the city's West End, with a population of 166,520 (2016). An independent municipality until annexed by the City of Montreal in 1910, NDG is today one half of the borough of Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grâce. It comprises two wards, Loyola to the west and Notre-Dame-de-Grâce to the east. NDG is bordered by four independent enclaves; its eastern border is shared with the City of Westmount, Quebec, to the north and west it is bordered by the cities of Montreal West, Hampstead and Côte-Saint-Luc. NDG plays a pivotal role in serving as the commercial and cultural hub for Montreal's predominantly English-speaking West End, with Sherbrooke Street West running the length of the community as the main commercial artery. The community is roughly bounded by Claremont Avenue to the east, Côte-Saint-Luc Road to the north, Brock Avenue in the west, and Highway 20 and the Saint-Jacques Escarpment to the south.

The Lachine Canal is a canal passing through the southwestern part of the Island of Montreal, Quebec, Canada, running 14.5 kilometres from the Old Port of Montreal to Lake Saint-Louis, through the boroughs of Lachine, Lasalle and Sud-Ouest.

Verdun is a borough (arrondissement) of the city of Montreal, Quebec, located in the southeastern part of the island.

Pointe-Saint-Charles is a neighbourhood in the borough of Le Sud-Ouest in the city of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Historically a working-class area, the creation of many new housing units, the recycling of industrial buildings into business incubators, lofts, and condos, the 2002 re-opening of the canal as a recreation and tourism area, the improvement of public spaces, and heritage enhancement have all helped transform the neighbourhood and attract new residents. Community groups continue to be pro-active in areas related to the fight against poverty and the improvement of living conditions.

Griffintown is a historic neighbourhood of Montreal, Quebec, southwest of downtown. The area existed as a functional neighbourhood from the 1820s until the 1960s and was mainly populated by Irish immigrants and their descendants. Mostly depopulated since then, the neighbourhood has been undergoing redevelopment since the early 2010s.

Ville-Marie is the name of a borough (arrondissement) in the centre of Montreal, Quebec. The borough is named after Fort Ville-Marie, the French settlement that would later become Montreal, which was located within the present-day borough. Old Montreal is a National Historic Site of Canada.

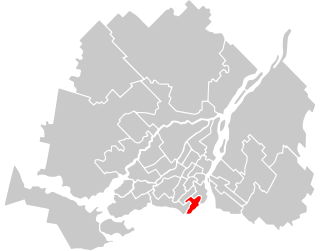

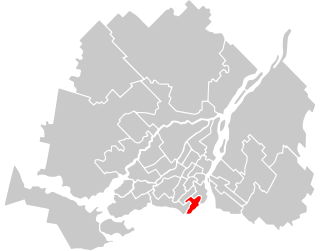

Le Sud-Ouest is a borough (arrondissement) of the city of Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Ville-Émard is a neighbourhood located in the Sud-Ouest borough of Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Downtown Montreal is the central business district of Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Atwater Market is a market hall located in the Saint-Henri area of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It opened in 1933. The interior market is home to many butchers and the Première Moisson bakery and restaurant. The outside market has many farmers' stalls, which sell both local and imported produce, as well as two cheese stores, a wine store and a fish store.

Little Burgundy is a neighbourhood in the South West borough of the city of Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Atwater Avenue is a major north–south street located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It links Doctor Penfield Avenue in the Ville-Marie borough to the north, and Henri Duhamel Street in the Verdun borough to the south. It is named for Edwin Atwater. The street runs through the Atwater Tunnel near the Atwater Market in Saint-Henri, before climbing and straddling the border of the city of Westmount.

The Canal de l'Aqueduc is an open-air aqueduct canal on the Island of Montreal in Quebec, Canada, serving part of the drinking water needs of the city of Montreal.

Côte-Saint-Paul is a neighbourhood located in the Southwest Borough of Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Benoit Dorais is a city councillor from Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He has served as the borough mayor of Le Sud-Ouest since 2009. From his first election to 2013, Dorais was a member of Vision Montreal, before joining Coalition Montréal in 2013 and Projet Montréal before the 2017 municipal election.

Jacqueline Montpetit is a politician in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She served on the Montreal city council from 2001 to 2009 and was borough mayor of Le Sud-Ouest. Montpetit has also served as a school commissioner.

LaSalle—Émard—Verdun is a federal electoral district in Montreal, Quebec. It was created by the 2012 federal electoral boundaries redistribution and was legally defined in the 2013 representation order. It came into effect upon the call of the 2015 Canadian federal election, held on 19 October 2015.

À St-Henri le cinq septembre is a 1962 National Film Board of Canada (NFB) documentary film directed by Hubert Aquin about the first day of school for children and their families in the working class Montreal district of Saint-Henri. As Aquin was primarily a writer, he worked with a variety of cameramen. The NFB credits 11 on the film—Guy Borremans, Michel Brault, Georges Dufaux, Claude Fournier, Bernard Gosselin, Jean Roy, Claude Jutra, Bernard Devlin, Arthur Lipsett, Don Owen and Daniel Fournier. Caroline Zéau in her book L'Office national du film et le cinéma canadien (1939-2003): éloge de la frugalité states that as many as 28 filmmakers worked on the project, including the entire French production team, with Jacques Godbout reading narration.

Saint Patrick Street is a street in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.