Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 312 (VMFA-312) is a United States Marine Corps F/A-18C Hornet squadron. Also known as the "Checkerboards", the squadron is based at Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, South Carolina and falls under the command of Marine Aircraft Group 31 (MAG-31) and the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing. The Radio Callsign is "Check."

Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 533 (VMFA-533) is a United States Marine Corps F-35B squadron. Also known as the "Hawks", the squadron is based at Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, South Carolina and falls under the command of Marine Aircraft Group 31 (MAG-31) and the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing.

Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 531 (VMFA-531) was a United States Marine Corps fighter squadron consisting of various types aircraft from its inception culminating with the F/A-18 Hornet. Known as the "Grey Ghosts", the squadron participated in action during World War II and the Vietnam War. They were decommissioned on March 27, 1992.

Marine Air Control Squadron 1 (MACS-1) is a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron. The squadron provides aerial surveillance, air traffic control, ground-controlled intercept, and aviation data-link connectivity for the I Marine Expeditionary Force. It was the first air warning squadron commissioned as part of the Marine Corps' new air warning program and is the second oldest aviation command and control unit in the Marine Corps. The squadron is based at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma and falls under Marine Air Control Group 38 and the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing.

Marine Air Control Group 28 (MACG-28) is a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control unit based at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point that is currently composed of four command and control squadrons and a low altitude air defense battalion that provide the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing with airspace coordination, air control, immediate air support, fires integration, air traffic control (ATC), radar surveillance, aviation combat element (ACE) communications support, and an integrated ACE command post in support of the II Marine Expeditionary Force.

Marine Air Control Squadron 2 (MACS-2) is a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron. The squadron provides aerial surveillance, Ground-controlled interception, and air traffic control for the II Marine Expeditionary Force. They are based at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point and fall under Marine Air Control Group 28 and the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing.

Marine Aviation and Training Support Group 33 (MATSG-33) is a United States Marine Corps aviation training group that was originally established during World War II as Marine Aircraft Group 33 (MAG-33). Fighter squadrons from MAG-33 fought most notably during the Battle of Okinawa and also as the first Marine aviation units to support the Korean War when they arrived as part of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade. They helped stabilize the United Nations positions during the Battle of Pusan Perimeter and fought in Korea for the remainder of the war. At some point in the 1960s, the group was deactivated and was not reactivated until 2000, when Marine Aviation Training Support Group at Naval Air Station Oceana, Virginia was renamed MATSG-33.

Air Warning Squadron 2 (AWS-2) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron during World War II. The squadron was tasked to provide aerial surveillance and early warning during amphibious assaults. They took part in the Battle of Guam in 1944 and would eventually move to Peleliu in 1945 assuming responsibility for air defense in that sector until the end of the war. The squadron departed Peleliu for the United States in January 1946 and was quickly decommissioned upon its arrival in California. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-2 to include Marine Air Control Squadron 2 (MACS-2).

Air Warning Squadron 8 (AWS-8) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control unit that provided aerial surveillance and early warning of enemy aircraft during World War II. The squadron was commissioned on March 3, 1944 and was one of five Marine Air Warning Squadrons that provided land based radar coverage during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. AWS-8, utilizing the callsign "Arsenic," remained on Okinawa as part of the garrison force following the Surrender of Japan. The squadron departed Okinawa for the United States in February 1946 and was quickly decommissioned upon its arrival in California. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-8 to include Marine Air Control Squadron 8 (MACS-8).

Air Warning Squadron 6 (AWS-6) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control unit that provided aerial surveillance and early warning of enemy aircraft during World War II. The squadron was activated on January 1, 1944 and was one of five Marine Air Warning Squadrons that provided land based radar coverage during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. AWS-6 remained on Okinawa as part of the garrison force following the Surrender of Japan. The squadron departed Okinawa for the United States in February 1946 and was quickly decommissioned upon its arrival in California. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-6 to include Marine Air Control Squadron 6 (MACS-6).

Robert O. Bisson was a brigadier general in the United States Marine Corps who served in both World War II and the Korean War. A naval aviator and communications engineer, he was at the forefront of the Marine Corps' use of radar for early warning and fighter direction. In 1943, as a member of VMF(N)-531, he supervised the installation and operation of the Marine Corps' first ground-controlled interception (GCI) equipment utilized in a combat zone. During the Battle of Okinawa he commanded the headquarters responsible for coordinating the Marine Corps' ground-based air defense units.

Air Warning Squadron 3 (AWS-3) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron during World War II. The squadron's primary mission was to provide aerial surveillance and early warning of approaching enemy aircraft during amphibious assaults. The squadron participated in the Philippines campaign (1944–1945) in support of the Eighth Army on Mindanao. AWS-3 was decommissioned shortly after the war in October 1945 at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, California. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-3 to include the former Marine Air Control Squadron 3 (MACS-3).

Assault Air Warning Squadrons were United States Marine Corps aviation command and control units formed during World War II to provide early warning, aerial surveillance, and ground controlled interception during the early phases of amphibious landing. These squadrons were supposed to be fielded lightweight radars and control center gear in order to operate for a limited duration at the beginning of any operation until larger air warning squadrons came ashore. Four of these squadrons were commissioned during the war with one, AWS(AT)-5, taking part in the Battle of Saipan. All four squadrons were decommissioned on November 10, 1944 because the Marine Corps was unable to field the required mobile radars. The "first in" capability that the Assault Air Warning Squadrons were supposed to provide was transferred to the Early Warning Teams that were added to the tables of organization for the regular air warning squadrons.

Edward Colston Dyer was a brigadier general in the United States Marine Corps who served in both World War II and the Korean War. A naval aviator and communications engineer, during his career he was a pioneer in the Marine Corps' development of early warning radar, night fighters, and helicopters.

Air Warning Squadron 4 (AWS-4) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron during World War II. The squadron's primary mission was to provide aerial surveillance and early warning of approaching enemy aircraft during amphibious assaults. The squadron participated in the Philippines campaign (1944–1945) in support of the Eighth Army on Mindanao. AWS-4 was decommissioned shortly after the war in October 1945. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-4 to include Marine Air Control Squadron 4 (MACS-4).

Air Warning Squadron 9 (AWS-9) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron during World War II. The squadron's primary mission was to provide aerial surveillance and early warning of approaching enemy aircraft during amphibious assaults. Formed in April 1944, the squadron did not deploy overseas until after the end of the war. It arrived in Tokyo Bay to take part in the occupation of Japan only to find out it was not required. The squadron returned to the U.S. and was decommissioned shortly after in December 1945. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-9 to include the former Marine Air Control Squadron 9 (MACS-9).

Marine Fighter Squadron 541 (VMF-541) was a reserve fighter squadron of the United States Marine Corps. Originally commissioned during World War II as a night fighter unit flying the F6F-5N Hellcat, the squadron participated in combat action over Peleliu and while supporting the liberation of the Philippines in 1944–45. During the war, VMF(N)-541 was credited with downing 23 Japanese aircraft. Following the war, the squadron participated in the occupation of Northern China until returning to the States to be decommissioned on April 20, 1946. The squadron was reactivated sometime after the war in the Marine Corps Reserve until being decommissioned again in the early 1960s.

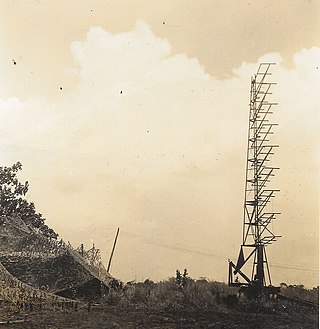

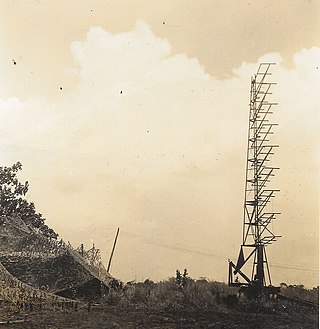

The Marine Corps Early Warning Detachment, Guadalcanal (1942–43) was a ground based early-warning radar detachment that provided long range detection and rudimentary fighter direction against Japanese air raids during the Battle of Guadalcanal. Initially deployed as part of the headquarters of Marine Aircraft Group 23, this detachment established an SCR-270 long range radar that allowed the Cactus Air Force to husband its critically short fighter assets during the early stages of the battle when control of the island was still very much in doubt. The detachment arrived on Guadalcanal on August 28, 1942, began operating in mid-September, and did not depart until early March 1943. Combat lessons learned from this detachment had a great deal of influence on the Marine Corps' development of its own organic, large scale air warning program which began in early 1943.

Marine Night Fighter Squadron 532 was a United States Marine Corps night fighter squadron that was commissioned during World War II. The squadron, which flew the F4U-2 Corsair, was the second night fighter squadron commissioned by the Marine Corps, the first to fly a single-seat, radar-equipped night fighter, and the only Marine squadron to fly the F4U-2 in combat. VMF(N)-532 saw extensive combat operations throughout 1944 in support of Marine Corps operations at Kwajalein Atoll and the Mariana Islands. The squadron was decommissioned on May 31, 1947, as part of the post-war draw down of the service. Since then, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of VMF(N)-532.

Marine Night Fighter Squadron 534 was a United States Marine Corps night fighter squadron that was commissioned during World War II. It was the fourth night fighter squadron commissioned in the service and participated in limited combat operations throughout 1944 and 1945 during Marine Corps operations over Kwajalein Atoll and the Mariana Islands. The squadron was decommissioned on May 31, 1947, as part of the post-war draw down of the service. Since then, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of VMF(N)-534.