The Dawes Act of 1887 regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the President of the United States to subdivide Native American tribal communal landholdings into allotments for Native American heads of families and individuals. This would convert traditional systems of land tenure into a government-imposed system of private property by forcing Native Americans to "assume a capitalist and proprietary relationship with property" that did not previously exist in their cultures. Before private property could be dispensed, the government had to determine which Indians were eligible for allotments, which propelled an official search for a federal definition of "Indian-ness".

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States government for the relocation of Native Americans who held original Indian title to their land as an independent nation-state. The concept of an Indian territory was an outcome of the U.S. federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), the policy of the U.S. government was one of assimilation.

Tribal sovereignty in the United States is the concept of the inherent authority of Indigenous tribes to govern themselves within the borders of the United States.

Water resources law is the field of law dealing with the ownership, control, and use of water as a resource. It is most closely related to property law, and is distinct from laws governing water quality.

Riparian water rights is a system for allocating water among those who possess land along its path. It has its origins in English common law. Riparian water rights exist in many jurisdictions with a common law heritage, such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and states in the eastern United States.

In the American legal system, prior appropriation water rights is the doctrine that the first person to take a quantity of water from a water source for "beneficial use" has the right to continue to use that quantity of water for that purpose. Subsequent users can take the remaining water for their own use if they do not impinge on the rights of previous users. The doctrine is sometimes summarized, "first in time, first in right".

Water right in water law is the right of a user to use water from a water source, e.g., a river, stream, pond or source of groundwater. In areas with plentiful water and few users, such systems are generally not complicated or contentious. In other areas, especially arid areas where irrigation is practiced, such systems are often the source of conflict, both legal and physical. Some systems treat surface water and ground water in the same manner, while others use different principles for each.

The Cherokee Nation, formerly known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three federally recognized tribes of Cherokees in the United States. It includes people descended from members of the Old Cherokee Nation who relocated, due to increasing pressure, from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokees who were forced to relocate on the Trail of Tears. The tribe also includes descendants of Cherokee Freedmen, Absentee Shawnee, and Natchez Nation. As of 2023, over 450,000 people were enrolled in the Cherokee Nation.

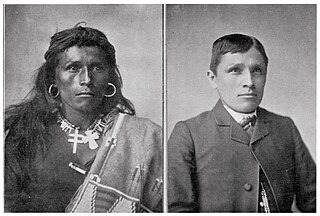

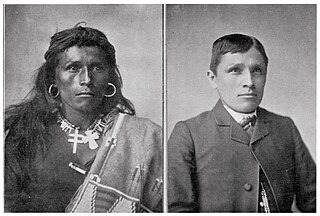

A series of efforts were made by the United States to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream European–American culture between the years of 1790 and 1920. George Washington and Henry Knox were first to propose, in the American context, the cultural assimilation of Native Americans. They formulated a policy to encourage the so-called "civilizing process". With increased waves of immigration from Europe, there was growing public support for education to encourage a standard set of cultural values and practices to be held in common by the majority of citizens. Education was viewed as the primary method in the acculturation process for minorities.

Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation, 362 U.S. 99 (1960), was a case decided by the United States Supreme Court that determined that the Federal Power Commission was authorized to take lands owned by the Tuscarora Indian tribe by eminent domain under the Federal Power Act for a hydroelectric power project, upon payment of just compensation.

United States v. Winans, 198 U.S. 371 (1905), was a U.S. Supreme Court case that held that the Treaty with the Yakima of 1855, negotiated and signed at the Walla Walla Council of 1855, as well as treaties similar to it, protected the Indians' rights to fishing, hunting and other privileges.

The Oklahoma Water Resources Board (OWRB) is an agency in the government of Oklahoma under the Governor of Oklahoma. OWRB is responsible for managing and protection the water resources of Oklahoma as well as for planning for the state's long-range water needs. The Board is composed of nine members appointed by the Governor with the consent of the Oklahoma Senate. The Board, in turn, appoints an Executive Director to administer the agency.

Winters v. United States, 207 U.S. 564 (1908), was a United States Supreme Court case clarifying water rights of American Indian reservations. This doctrine was meant to clearly define the water rights of indigenous people in cases where the rights were not clear. The case was first argued on October 24, 1907, and a decision was reached January 6, 1908. This case set the standards for the United States government to acknowledge the vitality of indigenous water rights, and how rights to the water relate to the continuing survival and self-sufficiency of indigenous people.

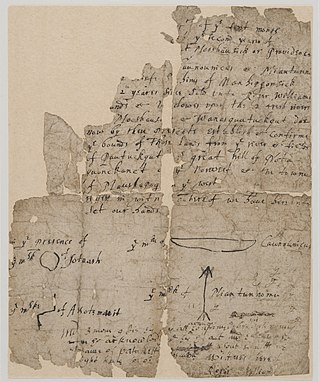

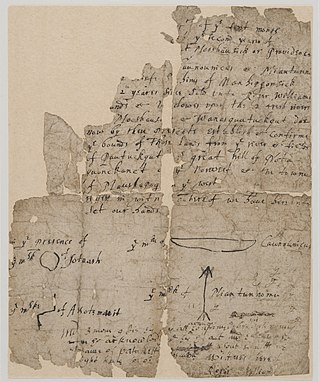

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

The McCarran Amendment, 43 U.S.C. § 666 (1952) is a federal law enacted by the United States Congress in 1952 which waives the United States' sovereign immunity in suits concerning ownership or management of water rights. It amended Chapter 15 of Title 43 of the United States Code. The McCarran Amendment gives others the right to join in such a lawsuit as a defendant. Prior to the Amendment, sovereign immunity kept the United States from being joined in any suits. The Amendment enabled suits concerning federal water rights to be tried in state courts.

An Organic Act is a generic name for a statute used by the United States Congress to describe a territory, in anticipation of being admitted to the Union as a state. Because of Oklahoma's unique history an explanation of the Oklahoma Organic Act needs a historic perspective. In general, the Oklahoma Organic Act may be viewed as one of a series of legislative acts, from the time of Reconstruction, enacted by Congress in preparation for the creation of a united State of Oklahoma. The Organic Act created Oklahoma Territory, and Indian Territory that were Organized incorporated territories of the United States out of the old "unorganized" Indian Territory. The Oklahoma Organic Act was one of several acts whose intent was the assimilation of the tribes in Oklahoma and Indian Territories through the elimination of tribes' communal ownership of property.

Lux v. Haggin, 69 Cal. 255; 10 P. 674; (1886), is a historic case in the conflict between riparian and appropriative water rights. Decided by a vote of four to three in the Supreme Court of California, the ruling held that appropriative rights were secondary to riparian rights.

Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community, 572 U.S. 782 (2014), was a United States Supreme Court case examining whether a federal court has jurisdiction over activity that violates the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act but takes place off Indian lands, and, if so, whether tribal sovereign immunity prevents a state from suing in federal court. In a 5–4 decision, the Court held that the State of Michigan's suit against Bay Mills is barred by tribal immunity.

Sharp v. Murphy, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a Supreme Court of the United States case of whether Congress disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation. After holding the case from the 2018 term, the case was decided on July 9, 2020, in a per curiam decision following McGirt v. Oklahoma that, for the purposes of the Major Crimes Act, the reservations were never disestablished and remain Native American country.

McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case which held that the domain reserved for the Muscogee Nation by Congress in the 19th century has never been disestablished and constitutes Indian country for the purposes of the Major Crimes Act, meaning that the State of Oklahoma has no right to prosecute American Indians for crimes allegedly committed therein. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals applied the McGirt rationale to rule nine other Indigenous nations had not been disestablished. As a result, almost the entirety of the eastern half of what is now the State of Oklahoma remains Indian country, meaning that criminal prosecutions of Native Americans for offenses therein falls outside the jurisdiction of Oklahoma’s court system. In these cases, jurisdiction properly vests within the Indigenous judicial systems and the federal district courts under the Major Crimes Act.