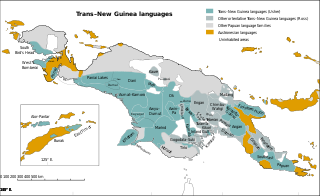

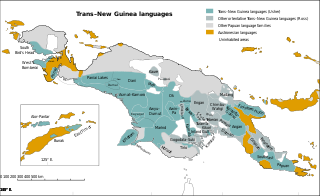

Trans–New Guinea (TNG) is an extensive family of Papuan languages spoken on the island of New Guinea and neighboring islands, a region corresponding to the country Papua New Guinea as well as parts of Indonesia.

The Papuan languages are the non-Austronesian languages spoken on the western Pacific island of New Guinea, as well as neighbouring islands in Indonesia, Solomon Islands, and East Timor. It is a strictly geographical grouping, and does not imply a genetic relationship.

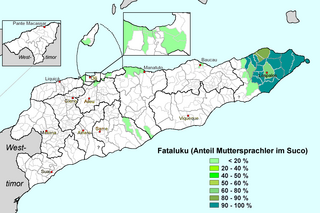

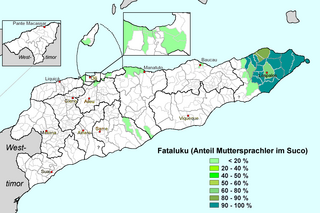

Fataluku is a Papuan language spoken by approximately 37,000 people of Fataluku ethnicity in the eastern areas of East Timor, especially around Lospalos. It is a member of the Timor-Alor-Pantar language family, which includes languages spoken both in East Timor and nearby regions of Indonesia. Fataluku's closest relative is Oirata, spoken on Kisar island, in the Moluccas of Indonesia. Fataluku is given the status of a national language under the constitution. Speakers of Fataluku normally have a command of Tetum and/or Indonesian, those speakers who are educated under Portuguese rule or from younger generation educated under Portuguese-language educational system during independence speak Portuguese.

The West Papuan languages are a proposed language family of about two dozen non-Austronesian languages of the Bird's Head Peninsula of far western New Guinea, the island of Halmahera and its vicinity, spoken by about 220,000 people in all. It is not established if they constitute a proper linguistic family or an areal network of genetically unrelated families.

The Eastern Trans-Fly languages are a small independent family of Papuan languages spoken in the Oriomo Plateau to the west of the Fly River in New Guinea.

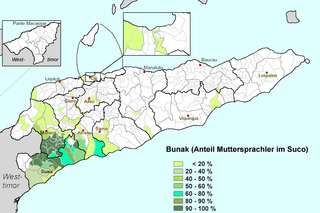

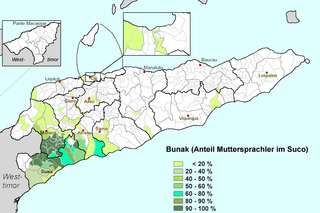

The Bunak language is the language of the Bunak people of the mountainous region of central Timor, split between the political boundary between West Timor, Indonesia, particularly in Lamaknen District and East Timor. It is one of the few on Timor which is not an Austronesian language, but rather a Papuan language of the Timor–Alor–Pantar language family. The language is surrounded by Malayo-Polynesian languages, like Uab Meto and Tetum.

Kâte is a Papuan language spoken by about 6,000 people in the Finschhafen District of Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea. It is part of the Finisterre–Huon branch of the Trans–New Guinea language family. It was adopted for teaching and mission work among speakers of Papuan languages by the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea in the early 1900s and at one time had as many as 80,000 second-language speakers.

The Marind–Yaqai (Marind–Yakhai) languages are a well established language family of Papuan languages, spoken by the Marind-anim. They form part of the Trans–New Guinea languages in the classifications of Stephen Wurm and Malcolm Ross, and were established as part of the Anim branch of TNG by Timothy Usher.

The Pauwasi languages are a likely family of Papuan languages, mostly in Indonesia. The subfamilies are at best only distantly related. The best described Pauwasi language is Karkar, across the border in Papua New Guinea. They are spoken around the headwaters of the Pauwasi River in the Indonesian-PNG border region.

The Mek languages are a well established family of Papuan languages spoken by the Mek people and Yali people. They form a branch of the Trans–New Guinea languages (TNG) in the classifications of Stephen Wurm (1975) and of Malcolm Ross (2005).

The Dani or Baliem Valley languages are a family of clearly related Trans–New Guinea languages spoken by the Dani and related peoples in the Baliem Valley in the Highland Papua, Indonesia. Foley (2003) considers their Trans–New Guinea language group status to be established. They may be most closely related to the languages of Paniai Lakes, but this is not yet clear. Capell (1962) posited that their closest relatives were the Kwerba languages, which Ross (2005) rejects.

The (Greater) West Bomberai languages are a family of Papuan languages spoken on the Bomberai Peninsula of western New Guinea and in East Timor and neighboring islands of Indonesia.

The Alor–Pantar languages are a family of clearly related Papuan languages spoken on islands of the Alor archipelago near Timor in southern Indonesia. They may be most closely related to the Papuan languages of eastern Timor, but this is not yet clear. A more distant relationship with the Trans–New Guinea languages of the Bomberai peninsula of Western New Guinea has been proposed based on pronominal evidence, but though often cited has never been firmly established.

The Timor–Alor–Pantar (TAP) languages are a family of languages spoken in Timor, Kisar, and the Alor archipelago in Southern Indonesia. It is the westernmost Papuan language family that survives, and one of two such outlier families in east Nusantara.

The Eleman languages are a family spoken around Kerema Bay, Papua New Guinea.

The Kwalean or Humene–Uare languages are a small family of Trans–New Guinea languages spoken in the "Bird's Tail" of New Guinea. They are classified within the Southeast Papuan branch of Trans–New Guinea.

The West Trans–New Guinea languages are a suggested linguistic linkage of Papuan languages, not well established as a group, proposed by Malcolm Ross in his 2005 classification of the Trans–New Guinea languages. Ross suspects they are an old dialect continuum, because they share numerous features that have not been traced to a single ancestor using comparative historical linguistics. The internal divisions of the languages are also unclear. William A. Foley considers the TNG identity of the Irian Highlands languages at least to be established.

The Dani–Kwerba languages were a hypothetical language family proposed by Arthur Capell in 1962 and adopted by Stephen Wurm as part of his Trans–New Guinea (TNG) phylum. Malcolm Ross reassigned the Dani languages to a West Trans–New Guinea linkage and the Kwerba languages to his Tor–Kwerba family, outside of TNG altogether.

The Oirata–Makasae, or Eastern Timor, languages are a small family of Papuan languages spoken in eastern Timor and the neighboring island of Kisar.

Proto-Trans–New Guinea is the reconstructed proto-language ancestral to the Trans–New Guinea languages. Reconstructions have been proposed by Malcolm Ross and Andrew Pawley.