The interwar Communist Party of Poland was a communist party active in Poland during the Second Polish Republic. It resulted from a December 1918 merger of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL) and the Polish Socialist Party – Left into the Communist Workers' Party of Poland. The communists were a small force in Polish politics.

The Polish Workers' Party was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 1948 to form the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR). From the end of World War II the PPR ruled Poland, with the Soviet Union exercising moderate influence. During the PPR years, the conspiratorial as well as legally permitted centers of opposition activity were largely eliminated, while a communist system was gradually established in the country.

Wincenty Witos was a Polish politician, prominent member and leader of the Polish People's Party (PSL), who served three times as the Prime Minister of Poland in the 1920s.

The Polish Socialist Party is a socialist political party in Poland.

The May Coup was a coup d'état carried out in Poland by Marshal Józef Piłsudski from 12 to 14 May 1926. The attack of Piłsudski's supporters on government forces resulted in an overthrow of the democratically-elected government of President Stanisław Wojciechowski and Prime Minister Wincenty Witos and caused hundreds of fatalities. A new government was installed, headed by Kazimierz Bartel. Ignacy Mościcki became president. Piłsudski remained the dominant politician in Poland until his death in 1935.

Ignacy Ewaryst Daszyński was a Polish socialist politician, journalist, and very briefly Prime Minister of the Second Polish Republic's first government, formed in Lublin in 1918.

The Polish Committee of National Liberation, also known as the Lublin Committee, was an executive governing authority established by the Soviet-backed communists in Poland at the later stage of World War II. It was officially proclaimed on 22 July 1944 in Chełm, installed on 26 July in Lublin and placed formally under the direction of the State National Council. The PKWN was a provisional entity functioning in opposition to the London-based Polish government-in-exile, which was recognized by the Western allies. The PKWN exercised control over Polish territory retaken from Nazi Germany by the Soviet Red Army and the Polish People's Army. It was sponsored and controlled by the Soviet Union and dominated by Polish communists.

Edward Franciszek Szczepanik was a Polish economist and the last Prime Minister of the Polish Government in Exile.

Tydzień Polski is the successor title to the Dziennik Polski i Dziennik Żołnierza, commonly known as Dziennik Polski, The Polish Daily, which was the first Polish language Daily newspaper continuously published in the United Kingdom from 12 July 1940 to July 2015. On 17 July 2015 it became a weekly publication, Tydzień Polski, The Polish Week.

Tadeusz Żenczykowski, pseudonym Kania, Kowalik and Zawadzki was a Polish lawyer, political activist and soldier in the Armia Krajowa during World War II, taking part in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Immediately after the war, he was a member of the anti-communist conspiracy in Poland. In 1945, he emigrated and became a journalist and deputy chief of the Polish Section of Radio Free Europe, historian and publicist.

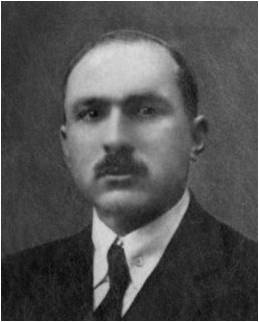

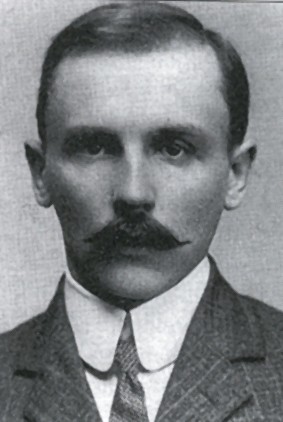

Kazimierz Pużak (1883–1950) was a Polish politician of the interwar period. Active in the Polish Socialist Party, he was one of the leaders of the Polish Secret State and Polish resistance, sentenced by the Soviets in the infamous Trial of the Sixteen in 1945.

Wacław Iwaniuk. Educated in Warsaw and Cambridge, England, a poet, literary critic and essayist for various Polish émigré newspapers in Canada and abroad. He served in the Polish Diplomatic Corps and as an officer in the Polish Armed Forces during World War II. Iwaniuk immigrated to Canada in 1948 (Toronto) where he continued to write and published in Polish. He was a member of several international literary societies (PEN) and writers unions. During his career as a postwar émigré poet and writer, he had published numerous articles and publications including in popular Polish Kultura paryska.

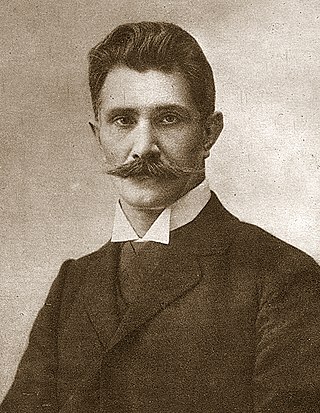

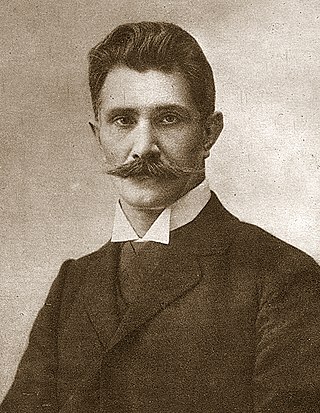

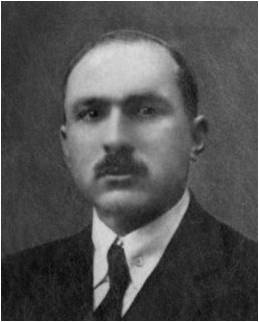

Tytus Filipowicz (1873–1953) was a Polish politician and diplomat.

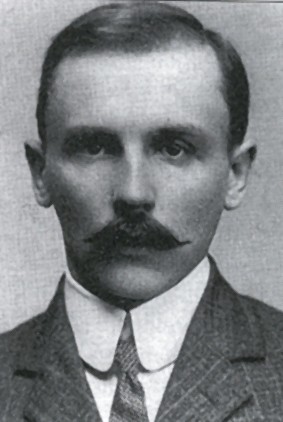

Adam Ignacy Koc was a Polish politician, MP, soldier, journalist and Freemason. Koc, who had several noms de guerre, fought in Polish units in World War I and in the Polish–Soviet War.

Adam Feliks Próchnik was a Polish socialist activist, politician and historian.

Wysłouch is the name of a Polish-Lithuanian aristocratic family. It traces its lineage back to 1385 when, along with other major Lithuanian noble clans, its forebears were admitted to the ranks of Polish nobility. The line begins with Stanisław Kościa, a Polish knight born in 1390; however, the first mention of the Wysłouch family name was recorded in a document dating from the first half of the 16th century. The Wysłouch family uses the "Odyniec" coat of arms.

Szymon Hołownia's Poland 2050 is a centrist political party in Poland.

Stefania Kossowska, née Szurlej was a Polish literary editor, political activist, writer and broadcaster.

Polska Fundacja Kulturalna (PFK), is an expatriate Polish publishing house, founded in London in 1950 to help maintain Polish culture among Poles who had been resettled in the UK after WWII. It is based at the Polish Social and Cultural Centre, known as POSK in King Street, Hammersmith, London. It is housed there along with a number of other organisations which serve Polish expatriates and others interested in Polish culture.