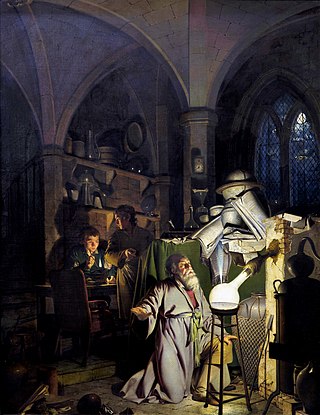

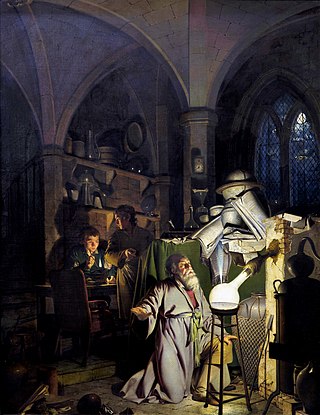

Alchemy is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD. Greek-speaking alchemists often referred to their craft as "the Art" (τέχνη) or "Knowledge" (ἐπιστήμη), and it was often characterised as mystic (μυστική), sacred (ἱɛρά), or divine (θɛíα).

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to make an elixir of life which made possible rejuvenation and immortality.

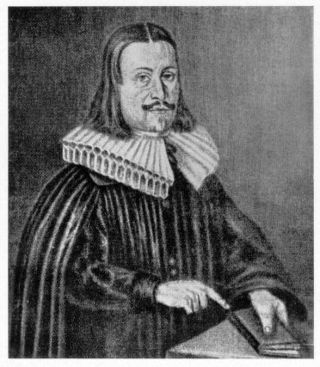

Jan Baptist van Helmont was a chemist, physiologist, and physician from Brussels. He worked during the years just after Paracelsus and the rise of iatrochemistry, and is sometimes considered to be "the founder of pneumatic chemistry". Van Helmont is remembered today largely for his 5-year willow tree experiment, his introduction of the word "gas" into the vocabulary of science, and his ideas on spontaneous generation.

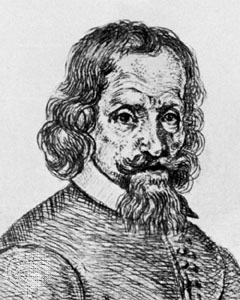

Andreas Libavius or Andrew Libavius was born in Halle, Germany c. 1550 and died in July 1616. Libavius was a renaissance man who spent time as a professor at the University of Jena teaching history and poetry. After which he became a physician at the Gymnasium in Rothenburg and later founded the Gymnasium at Coburg. Libavius was most known for practicing alchemy and writing a book called Alchemia, one of the first chemistry textbooks ever written.

Johann Rudolf Glauber was a German-Dutch alchemist and chemist. Some historians of science have described him as one of the first chemical engineers. His discovery of sodium sulfate in 1625 led to the compound being named after him: "Glauber's salt".

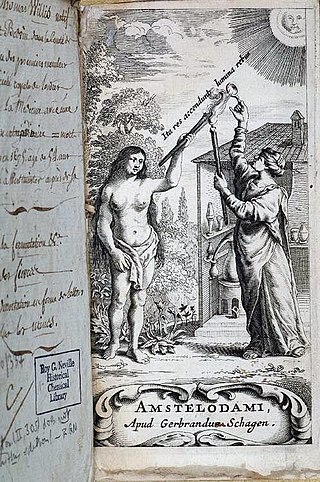

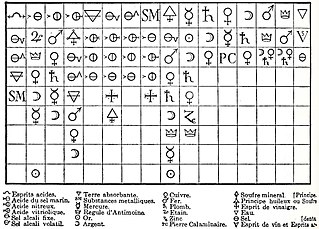

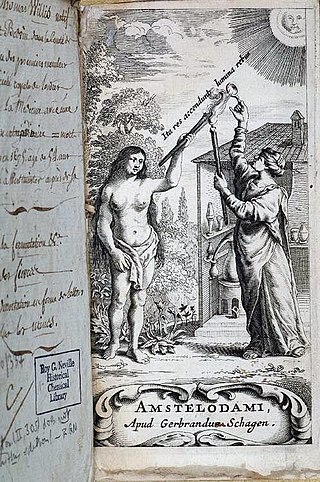

Azoth is a universal remedy or potent solvent sought after in the realm of alchemy, akin to alkahest—a distinct alchemical substance. The quest for Azoth was the crux of numerous alchemical endeavors, symbolized by the Caduceus. Initially coined to denote an esoteric formula pursued by alchemists, akin to the Philosopher's Stone, the term Azoth later evolved into a poetic expression for the element mercury. The etymology of 'Azoth' traces to Medieval Latin as a modification of 'azoc,' ultimately derived from the Arabic al-za'buq (الزئبق), meaning 'the mercury.'

Chinese alchemy is a historical Chinese approach to alchemy, a pseudoscience. According to original texts such as the Cantong qi, the body is understood as the focus of cosmological processes summarized in the five agents of change, or Wuxing, the observation and cultivation of which leads the practitioner into alignment and harmony with the Tao. Therefore, the traditional view in China is that alchemy focuses mainly on longevity and the purification of one's spirit, mind and body, providing, health, longevity and wisdom, through the practice of Qigong and wuxingheqidao. The consumption and use of various concoctions known as alchemical medicines or elixirs, each of which having different purposes but largely were concerned with immortality.

Johann Kunckel, awarded Swedish nobility in 1693 under the Swedish name von Löwenstern-Kunckel and the German version of the name Kunckel von Löwenstern, German chemist, was born in 1630, near Rendsburg, his father being alchemist to the court of Holstein. He became chemist and apothecary to the dukes of Lauenburg, and then to the Elector of Saxony, Johann Georg II, who put him in charge of the royal laboratory at Dresden. Intrigues engineered against him caused him to resign this position in 1677, and for a time he lectured on chemistry at Annaberg and Wittenberg. Invited to Berlin by Frederick William, in 1679 he became director of the laboratory and glass works of Brandenburg. In 1688 the king of Sweden, Charles XI, brought him to Stockholm, ennobling him under the name von Löwenstern-Kunckel in 1693 and making him a member of the Bergskollegium, the Board of Mines. He died probably on 20 March 1703 near Stockholm.

Iatrochemistry is an archaic pre-scientific school of thought that was supplanted by modern chemistry and medicine. Having its roots in alchemy, iatrochemistry sought to provide chemical solutions to diseases and medical ailments.

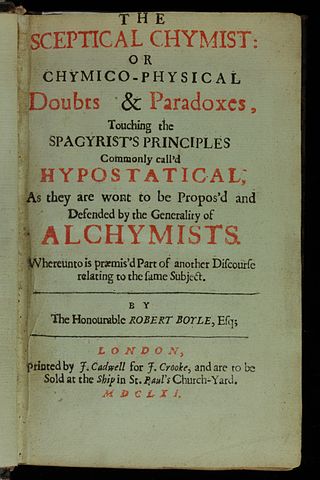

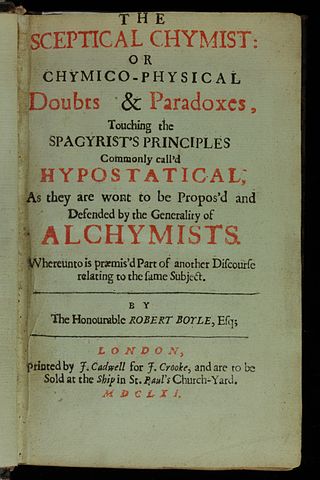

The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes is the title of a book by Robert Boyle, published in London in 1661. In the form of a dialogue, the Sceptical Chymist presented Boyle's hypothesis that matter consisted of corpuscles and clusters of corpuscles in motion and that every phenomenon was the result of collisions of particles in motion. Boyle also objected to the definitions of elemental bodies propounded by Aristotle and by Paracelsus, instead defining elements as "perfectly unmingled bodies". For these reasons Robert Boyle has sometimes been called the founder of modern chemistry.

In the history of chemistry, the chemical revolution, also called the first chemical revolution, was the reformulation of chemistry during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which culminated in the law of conservation of mass and the oxygen theory of combustion.

Corpuscularianism, also known as corpuscularism, is a set of theories that explain natural transformations as a result of the interaction of particles. It differs from atomism in that corpuscles are usually endowed with a property of their own and are further divisible, while atoms are neither. Although often associated with the emergence of early modern mechanical philosophy, and especially with the names of Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton, and John Locke, corpuscularian theories can be found throughout the history of Western philosophy.

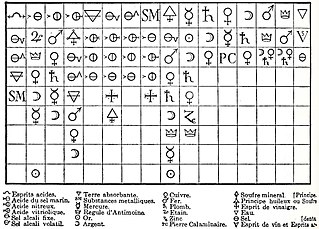

Principle, in chemistry, refers to a historical concept of the constituents of a substance, specifically those that produce a certain quality or effect in the substance, such as a bitter principle, which is any one of the numerous compounds having a bitter taste.

George Starkey (1628–1665) was a Colonial American alchemist, medical practitioner, and writer of numerous commentaries and chemical treatises that were widely circulated in Western Europe and influenced prominent men of science, including Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton. After relocating from New England to London, England, in 1650, Starkey began writing under the pseudonym Eirenaeus Philalethes. Starkey remained in England and continued his career in medicine and alchemy until his death in the Great Plague of London in 1665.

Diana's Tree, also known as the Philosopher's Tree, was considered a precursor to the philosopher's stone and resembled coral in regards to its structure. It is a dendritic amalgam of crystallized silver, obtained from mercury in a solution of silver nitrate; so-called by the alchemists, among whom "Diana" stood for silver. The arborescence of this amalgam, which even included fruit-like forms on its branches, led pre-modern chemical philosophers to theorize the existence of life in the kingdom of minerals.

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid or spirits of salt, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride (HCl). It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid. It is a component of the gastric acid in the digestive systems of most animal species, including humans. Hydrochloric acid is an important laboratory reagent and industrial chemical.

John Webster (1610–1682), also known as Johannes Hyphastes, was an English cleric, physician and chemist with occult interests, a proponent of astrology and a sceptic about witchcraft. He is known for controversial works.

Lawrence M. Principe is the Drew Professor of the Humanities at Johns Hopkins University in the Department of History of Science and Technology and the Department of Chemistry. He is also currently the Director of the Charles Singleton Center for the Study of Premodern Europe, an interdisciplinary center for research at Johns Hopkins. He is the first recipient of the Francis Bacon Medal for significant contributions to the history of science. Principe's research has been supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Philosophical Society, the Chemical Heritage Foundation, and a 2015-2016 Guggenheim Fellowship. Principe is recognized as one of the foremost experts in the history of alchemy.

Robert Child (1613–1654) was an English physician, agriculturalist and alchemist. A recent view is that his approach to agriculture belongs to the early ideas on political economy.