Obstetrics is the field of study concentrated on pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. As a medical specialty, obstetrics is combined with gynecology under the discipline known as obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN), which is a surgical field.

Placenta praevia is when the placenta attaches inside the uterus but in a position near or over the cervical opening. Symptoms include vaginal bleeding in the second half of pregnancy. The bleeding is bright red and tends not to be associated with pain. Complications may include placenta accreta, dangerously low blood pressure, or bleeding after delivery. Complications for the baby may include fetal growth restriction.

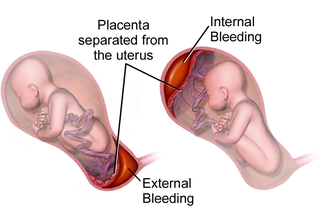

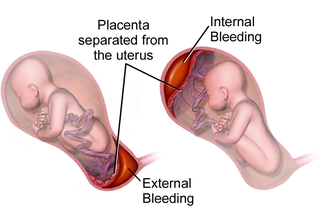

Placental abruption is when the placenta separates early from the uterus, in other words separates before childbirth. It occurs most commonly around 25 weeks of pregnancy. Symptoms may include vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, and dangerously low blood pressure. Complications for the mother can include disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and kidney failure. Complications for the baby can include fetal distress, low birthweight, preterm delivery, and stillbirth.

Vaginal bleeding is any expulsion of blood from the vagina. This bleeding may originate from the uterus, vaginal wall, or cervix. Generally, it is either part of a normal menstrual cycle or is caused by hormonal or other problems of the reproductive system, such as abnormal uterine bleeding.

Bloody show or show is the passage of a small amount of blood or blood-tinged mucus through the vagina near the end of pregnancy. It is caused by thinning and dilation of the cervix, leading to detachment of the cervical mucus plug that seals the cervix during pregnancy and tearing of small cervical blood vessels, and is one of the signs that labor may be imminent. The bloody show may be expelled from the vagina in pieces or altogether and often appears as a jelly-like piece of mucus stained with blood. Although the bloody show may be alarming at first, it is not a concern of patient health after 37 weeks gestation.

Obstetrical bleeding is bleeding in pregnancy that occurs before, during, or after childbirth. Bleeding before childbirth is that which occurs after 24 weeks of pregnancy. Bleeding may be vaginal or less commonly into the abdominal cavity. Bleeding which occurs before 24 weeks is known as early pregnancy bleeding.

Complications of pregnancy are health problems that are related to, or arise during pregnancy. Complications that occur primarily during childbirth are termed obstetric labor complications, and problems that occur primarily after childbirth are termed puerperal disorders. While some complications improve or are fully resolved after pregnancy, some may lead to lasting effects, morbidity, or in the most severe cases, maternal or fetal mortality.

An abdominal pregnancy is a rare type of ectopic pregnancy where the embryo or fetus is growing and developing outside the uterus, in the abdomen, and not in a fallopian tube, an ovary, or the broad ligament.

Placenta accreta occurs when all or part of the placenta attaches abnormally to the myometrium. Three grades of abnormal placental attachment are defined according to the depth of attachment and invasion into the muscular layers of the uterus:

- Accreta – chorionic villi attached to the myometrium, rather than being restricted within the decidua basalis.

- Increta – chorionic villi invaded into the myometrium.

- Percreta – chorionic villi invaded through the perimetrium.

Uterine atony is the failure of the uterus to contract adequately following delivery. Contraction of the uterine muscles during labor compresses the blood vessels and slows flow, which helps prevent hemorrhage and facilitates coagulation. Therefore, a lack of uterine muscle contraction can lead to an acute hemorrhage, as the vasculature is not being sufficiently compressed. Uterine atony is the most common cause of postpartum hemorrhage, which is an emergency and potential cause of fatality. Across the globe, postpartum hemorrhage is among the top five causes of maternal death. Recognition of the warning signs of uterine atony in the setting of extensive postpartum bleeding should initiate interventions aimed at regaining stable uterine contraction.

Postpartum bleeding or postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is often defined as the loss of more than 500 ml or 1,000 ml of blood following childbirth. Some have added the requirement that there also be signs or symptoms of low blood volume for the condition to exist. Signs and symptoms may initially include: an increased heart rate, feeling faint upon standing, and an increased breathing rate. As more blood is lost, the patient may feel cold, blood pressure may drop, and they may become restless or unconscious. In severe cases circulatory collapse, disseminated intravascular coagulation and death can occur. The condition can occur up to twelve weeks following delivery in the secondary form. The most common cause is poor contraction of the uterus following childbirth. Not all of the placenta being delivered, a tear of the uterus, or poor blood clotting are other possible causes. It occurs more commonly in those who already have a low amount of red blood, are Asian, have a larger fetus or more than one fetus, are obese or are older than 40 years of age. It also occurs more commonly following caesarean sections, those in whom medications are used to start labor, those requiring the use of a vacuum or forceps, and those who have an episiotomy.

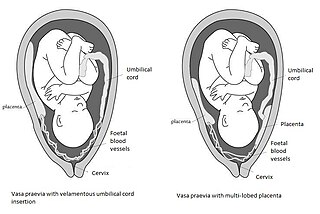

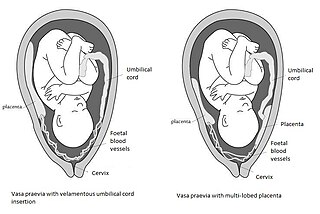

Vasa praevia is a condition in which fetal blood vessels cross or run near the internal opening of the uterus. These vessels are at risk of rupture when the supporting membranes rupture, as they are unsupported by the umbilical cord or placental tissue.

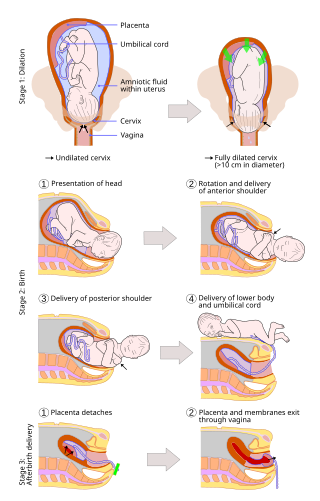

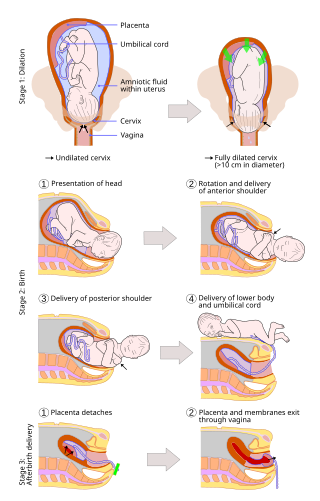

A vaginal delivery is the birth of offspring in mammals through the vagina. It is the most common method of childbirth worldwide. It is considered the preferred method of delivery, as it is correlated with lower morbidity and mortality than caesarean sections (C-sections), though it is not clear whether this is causal.

Velamentous cord insertion is a complication of pregnancy where the umbilical cord is inserted in the fetal membranes. It is a major cause of antepartum hemorrhage that leads to loss of fetal blood and associated with high perinatal mortality. In normal pregnancies, the umbilical cord inserts into the middle of the placental mass and is completely encased by the amniotic sac. The vessels are hence normally protected by Wharton's jelly, which prevents rupture during pregnancy and labor. In velamentous cord insertion, the vessels of the umbilical cord are improperly inserted in the chorioamniotic membrane, and hence the vessels traverse between the amnion and the chorion towards the placenta. Without Wharton's jelly protecting the vessels, the exposed vessels are susceptible to compression and rupture.

A placental disease is any disease, disorder, or pathology of the placenta.

An obstetric labor complication is a difficulty or abnormality that arises during the process of labor or delivery.

Chorionic hematoma is the pooling of blood (hematoma) between the chorion, a membrane surrounding the embryo, and the uterine wall. It occurs in about 3.1% of all pregnancies, it is the most common sonographic abnormality and the most common cause of first trimester bleeding.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to obstetrics:

Circumvallate placenta is a rare condition affecting about 1-2% of pregnancies, in which the amnion and chorion fetal membranes essentially "double back" on the fetal side around the edges of the placenta. After delivery, a circumvallate placenta has a thick ring of membranes on its fetal surface. Circumvallate placenta is a placental morphological abnormality associated with increased fetal morbidity and mortality due to the restricted availability of nutrients and oxygen to the developing fetus.

Early pregnancy bleeding is vaginal bleeding before 14 weeks of gestational age. If the bleeding is significant, hemorrhagic shock may occur. Concern for shock is increased in those who have loss of consciousness, chest pain, shortness of breath, or shoulder pain.