Strepsirrhini or Strepsirhini is a suborder of primates that includes the lemuriform primates, which consist of the lemurs of Madagascar, galagos ("bushbabies") and pottos from Africa, and the lorises from India and southeast Asia. Collectively they are referred to as strepsirrhines. Also belonging to the suborder are the extinct adapiform primates which thrived during the Eocene in Europe, North America, and Asia, but disappeared from most of the Northern Hemisphere as the climate cooled. Adapiforms are sometimes referred to as being "lemur-like", although the diversity of both lemurs and adapiforms does not support this comparison.

Prosimians are a group of primates that includes all living and extinct strepsirrhines, as well as the haplorhine tarsiers and their extinct relatives, the omomyiforms, i.e. all primates excluding the simians. They are considered to have characteristics that are more "primitive" than those of simians.

Haplorhini, the haplorhines or the "dry-nosed" primates is a suborder of primates containing the tarsiers and the simians, as sister of the Strepsirrhini ("moist-nosed"). The name is sometimes spelled Haplorrhini. The simians include catarrhines, and the platyrrhines.

Adapidae is a family of extinct primates that primarily radiated during the Eocene epoch between about 55 and 34 million years ago.

Lemuriformes is the sole extant infraorder of primate that falls under the suborder Strepsirrhini. It includes the lemurs of Madagascar, as well as the galagos and lorisids of Africa and Asia, although a popular alternative taxonomy places the lorisoids in their own infraorder, Lorisiformes.

The simians, anthropoids, or higher primates are an infraorder of primates containing all animals traditionally called monkeys and apes. More precisely, they consist of the parvorders Platyrrhini and Catarrhini, the latter of which consists of the family Cercopithecidae and the superfamily Hominoidea.

Eosimiidae is the possible family of extinct primates believed to be the earliest simians.

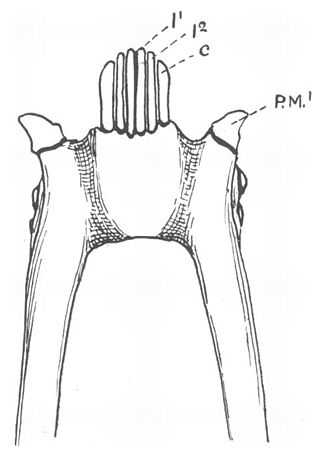

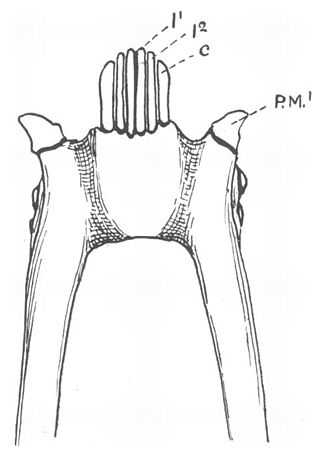

A toothcomb is a dental structure found in some mammals, comprising a group of front teeth arranged in a manner that facilitates grooming, similar to a hair comb. The toothcomb occurs in lemuriform primates, treeshrews, colugos, hyraxes, and some African antelopes. The structures evolved independently in different types of mammals through convergent evolution and vary both in dental composition and structure. In most mammals the comb is formed by a group of teeth with fine spaces between them. The toothcombs in most mammals include incisors only, while in lemuriform primates they include incisors and canine teeth that tilt forward at the front of the lower jaw, followed by a canine-shaped first premolar. The toothcombs of colugos and hyraxes take a different form with the individual incisors being serrated, providing multiple tines per tooth.

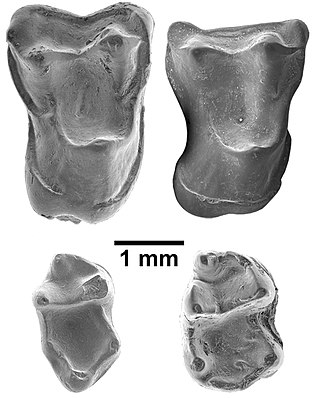

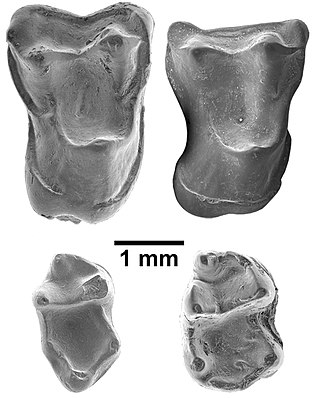

Altiatlasius is an extinct genus of mammal, which may have been the oldest known primate, dating to the Late Paleocene from Morocco. The only species, Altiatlasius koulchii, was described in 1990.

Darwinius is a genus within the infraorder Adapiformes, a group of basal strepsirrhine primates from the middle Eocene epoch. Its only known species, Darwinius masillae, lived approximately 47 million years ago based on dating of the fossil site.

Karanisia is an extinct genus of strepsirrhine primate from middle Eocene deposits in Egypt.

Bugtilemur is an extinct genus of Strepsirhine primate belonging to the adapiform family Ekgmowechashalidae.It is represented by only one species, B. mathesoni, which was found in the Chitarwata Formation of Pakistan.

Algeripithecus is an extinct genus of early fossil primate, weighing approximately 65 to 85 grams. Fossils have been found in Algeria dating from 50 to 46 million years ago.

Lemurs, primates belonging to the suborder Strepsirrhini which branched off from other primates less than 63 million years ago, evolved on the island of Madagascar, for at least 40 million years. They share some traits with the most basal primates, and thus are often confused as being ancestral to modern monkeys, apes, and humans. Instead, they merely resemble ancestral primates.

Azibius is an extinct genus of fossil primate from the late early or early middle Eocene from the Glib Zegdou Formation in the Gour Lazib area of Algeria. They are thought to be related to the living toothcombed primates, the lemurs and lorisoids, although paleoanthropologists such as Marc Godinot have argued that they may be early simians. Originally described as a type of plesiadapiform, its fragmentary remains have been interpreted as a hyopsodontid, an adapid, and a macroscelidid. Less fragmentary remains discovered between 2003 and 2009 demonstrated a close relationship between Azibius and Algeripithecus, a fossil primate once thought to be the oldest known simian. Descriptions of the talus in 2011 have helped to strengthen support for the strepsirrhine status of Azibius and Algeripithecus, which would indicate that the evolutionary history of lemurs and their kin is rooted in Africa.

Djebelemur is an extinct genus of early strepsirrhine primate from the late early or early middle Eocene period from the Chambi locality in Tunisia. Although they probably lacked a toothcomb, a specialized dental structure found in living lemuriforms, they are thought to be a related stem group. The one recognized species, Djebelemur martinezi, was very small, approximately 100 g (3.5 oz).

Djebelemuridae is an extinct family of early strepsirrhine primates from Africa. It consists of five genera. The organisms in this family were exceptionally small, and were insectivores. This family dates to the early to late Eocene. Although they gave rise to the crown strepsirrhines, which includes today's lemurs and lorisoids, they lacked the toothcomb that identifies that group.

Afrasia djijidae is a fossil primate that lived in Myanmar approximately 37 million years ago, during the late middle Eocene. The only species in the genus Afrasia, it was a small primate, estimated to weigh around 100 grams (3.5 oz). Despite the significant geographic distance between them, Afrasia is thought to be closely related to Afrotarsius, an enigmatic fossil found in Libya and Egypt that dates to 38–39 million years ago. If this relationship is correct, it suggests that early simians dispersed from Asia to Africa during the middle Eocene and would add further support to the hypothesis that the first simians evolved in Asia, not Africa. Neither Afrasia nor Afrotarsius, which together form the family Afrotarsiidae, is considered ancestral to living simians, but they are part of a side branch or stem group known as eosimiiforms. Because they did not give rise to the stem simians that are known from the same deposits in Africa, early Asian simians are thought to have dispersed from Asia to Africa more than once prior to the late middle Eocene. Such dispersals from Asia to Africa also were seen around the same time in other mammalian groups, including hystricognathous rodents and anthracotheres.

Plesiopithecus is an extinct genus of early strepsirrhine primate from the late Eocene.

Afradapis is a genus of adapiform primate that lived during the Late Eocene. The only known species, Afradapis longicristatus, was discovered in the Birket Qarun Formation in northern Egypt in 2009. While its geographic distribution is confined to Afro-Arabia, Afradapis belongs to the predominantly European adapiform family Caenopithecinae. This taxonomic placement is supported by recent phylogenetic analyses that recover a close evolutionary relationship between Afradapis and adapiforms, including Darwinius. While adapiforms have been noted for their strepsirrhine-like morphology, no adapiform fossil possesses the unique anatomical traits to establish an ancestor-descent relationship between caenopithecids and living strepsirrhines. It ate leaves and moved around slowly like lorises.