Basque is a language spoken by Basques and others of the Basque Country, a region that straddles the westernmost Pyrenees in adjacent parts of northern Spain and southwestern France. Linguistically, Basque is a language isolate. The Basques are indigenous to, and primarily inhabit, the Basque Country. The Basque language is spoken by 28.4% (751,500) of Basques in all territories. Of these, 93.2% (700,300) are in the Spanish area of the Basque Country and the remaining 6.8% (51,200) are in the French portion.

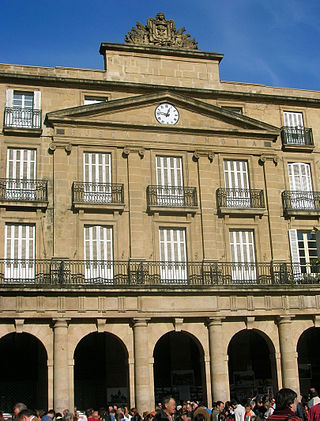

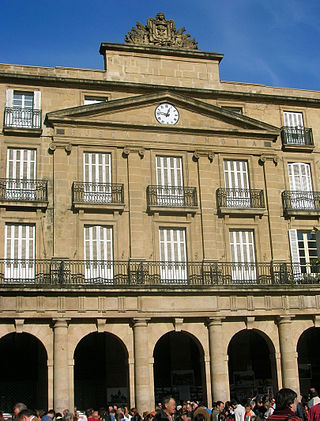

Euskaltzaindia is the official academic language regulatory institution which watches over the Basque language. It conducts research, seeks to protect the language, and establishes standards of use. It is known in Spanish as La Real Academia de la Lengua Vasca and in French as Académie de la Langue Basque.

The Basque alphabet is a Latin alphabet used to write the Basque language. It consists of 27 letters.

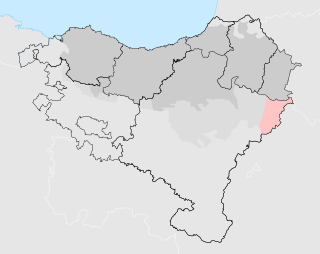

The French Basque Country, or Northern Basque Country, is a region lying on the west of the French department of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques. Since 1 January 2017, it constitutes the Basque Municipal Community presided over by Jean-René Etchegaray.

Iberian languages is a generic term for the languages currently or formerly spoken in the Iberian Peninsula.

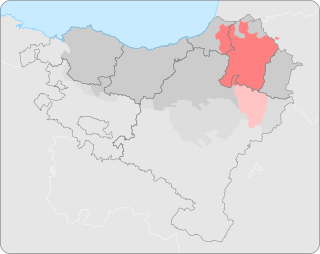

Biscayan, sometimes Bizkaian, is a dialect of the Basque language spoken mainly in Biscay, one of the provinces of the Basque Country of Spain.

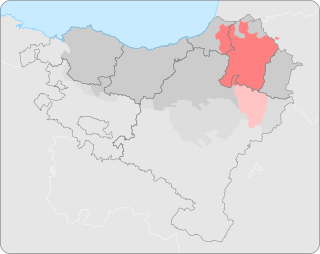

Gipuzkoan is a dialect of the Basque language spoken mainly in the central and eastern parts of the province of Gipuzkoa in Basque Country and also in the northernmost part of Navarre. It is a central dialect of Basque according to the traditional dialectal classification of the language based on research carried out by Lucien Bonaparte in the 19th century. He included varieties spoken in the Sakana and Burunda valleys also in the Gipuzkoan dialect, however this approach has been disputed by modern Basque linguists.

Navarro-Labourdin or Navarro-Lapurdian is a Basque dialect spoken in the Lower Navarre and Labourd (Lapurdi) former provinces of the French Basque Country. It consists of two dialects in older classifications, Lower Navarrese and Labourdin. It differs somewhat from Upper Navarrese spoken in the Peninsular Basque Country.

Souletin or Zuberoan is the Basque dialect spoken in Soule, France. Souletin is marked by influences from Occitan, especially in the lexicon. Another distinct characteristic is the use of xuka verb forms, a form of address including in third person verbs the interlocutor marker embedded in the auxiliary verb: jin da → jin düxü.

Standard Basque is a standardised version of the Basque language, developed by the Basque Language Academy in the late 1960s, which nowadays is the most widely and commonly spoken Basque-language version throughout the Basque Country. Heavily based on the literary tradition of the central areas, it is the version of the language that is commonly used in education at all levels, from elementary school to university, on television and radio, and in the vast majority of all written production in Basque.

Koldo Mitxelena Elissalt was an eminent Basque linguist. He taught in the Department of Philology at the University of the Basque Country, and was a member of the Royal Academy of the Basque Language.

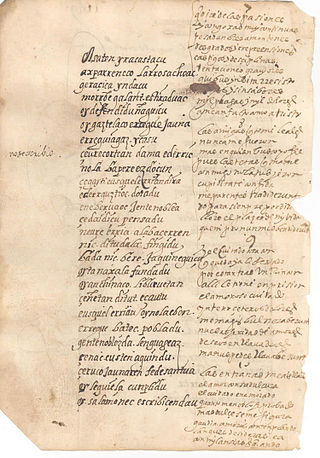

Joanes Leizarraga (1506–1601) was a 16th-century Basque priest. He is most famous for being the first to attempt the standardisation of the Basque language and for the translation of religious works into Basque, in particular the first Basque translation of the New Testament.

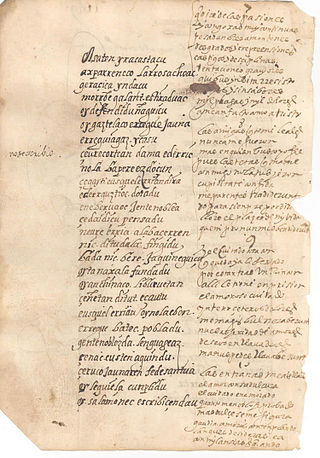

Although the first instances of coherent Basque phrases and sentences go as far back as the San Millán glosses of around 950, the large-scale damage done by periods of great instability and warfare, such as the clan wars of the Middle Ages, the Carlist Wars and the Spanish Civil War, led to the scarcity of written material predating the 16th century.

Resurrección María de Azkue was an influential Basque priest, musician, poet, writer, sailor and academic. He made several major contributions to the study of the Basque language and was the first head of the Euskaltzaindia, the Academy of the Basque Language. In spite of some justifiable criticism of an imbalance towards unusual and archaic forms and a tendency to ignore the Romance influence on Basque, he is considered one of the greatest scholars of Basque to date.

Salazarese is the Basque dialect of the Salazar Valley of Navarre, Spain.

Gorka Aulestia Txakartegi is Spanish Basque literary historian and lexicographer.

Koldo Zuazo is a Basque linguist, professor at the University of the Basque Country and specialist in Basque language dialectology and sociolinguistics.

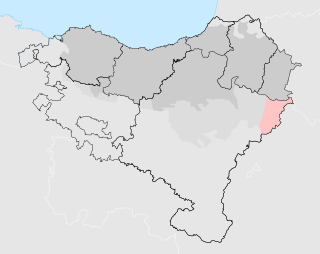

Roncalese is an extinct Basque dialect once spoken in the Roncal Valley in Navarre, Spain. It is a subdialect of Eastern Navarrese in the classification of Koldo Zuazo. It had been classified as a subdialect of Souletin in the 19th-century classification of Louis Lucien Bonaparte, and as a separate dialect in the early-20th-century classification of Resurrección María de Azkue. The last speaker of the Roncalese, Fidela Bernat, died in 1991.

Alavese is an extinct dialect of the Basque language spoken formerly in Álava, one of the provinces of the Basque Country of Spain. The modern-day communities of Aramaio and Legutio along the northern border with Biscay do not speak the Alavese dialect but a variant of the Biscayan dialect instead and while overall some 25% of people in Álava today are Basque speakers, the majority of these are speakers of Standard Basque who acquired Basque via the education system or moved there from other parts of the Basque Country.

16th-century Basque literature begins with three authors considered classics: Joan Perez de Lazarraga, Bernard Etxepare and Joanes Leizarraga. In the manuscript of the first of them, discovered in 2004, the influence of the traditional court lyric, the Italian novela pastoril and the popular Basque templates can be observed. In the case of Etxepare, often compared to the Archpriest of Hita, the influence of French literature has been mentioned. Regarding Leizarraga, translator into Basque of the New Testament and other works on religious themes, he stands out for his attempt to find a unified language—a concern of many of the later authors—and for his use of cultured verbal forms and compound sentences, nonexistent in written literature up to that time.