Related Research Articles

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vagina or anus, or through a puncture in the skin. Hypovolemia is a massive decrease in blood volume, and death by excessive loss of blood is referred to as exsanguination. Typically, a healthy person can endure a loss of 10–15% of the total blood volume without serious medical difficulties. The stopping or controlling of bleeding is called hemostasis and is an important part of both first aid and surgery.

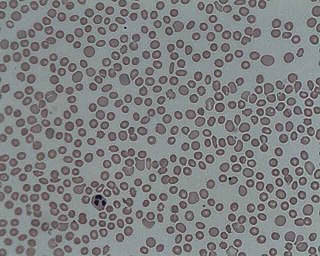

Platelets or thrombocytes are a blood component whose function is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping, thereby initiating a blood clot. Platelets have no cell nucleus; they are fragments of cytoplasm derived from the megakaryocytes of the bone marrow or lung, which then enter the circulation. Platelets are found only in mammals, whereas in other vertebrates, thrombocytes circulate as intact mononuclear cells.

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of coagulation involves activation, adhesion and aggregation of platelets, as well as deposition and maturation of fibrin.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a condition in which blood clots form throughout the body, blocking small blood vessels. Symptoms may include chest pain, shortness of breath, leg pain, problems speaking, or problems moving parts of the body. As clotting factors and platelets are used up, bleeding may occur. This may include blood in the urine, blood in the stool, or bleeding into the skin. Complications may include organ failure.

Von Willebrand disease (VWD) is the most common hereditary blood-clotting disorder in humans. An acquired form can sometimes result from other medical conditions. It arises from a deficiency in the quality or quantity of von Willebrand factor (VWF), a multimeric protein that is required for platelet adhesion. It is known to affect several breeds of dogs as well as humans. The three forms of VWD are hereditary, acquired, and pseudo or platelet type. The three types of hereditary VWD are VWD type 1, VWD type 2, and VWD type 3. Type 2 contains various subtypes. Platelet type VWD is also an inherited condition.

In biology, hemostasis or haemostasis is a process to prevent and stop bleeding, meaning to keep blood within a damaged blood vessel. It is the first stage of wound healing. Hemostasis involves three major steps:

In hematology, thrombocytopenia is a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of platelets in the blood. Low levels of platelets in turn may lead to prolonged or excessive bleeding. It is the most common coagulation disorder among intensive care patients and is seen in a fifth of medical patients and a third of surgical patients.

Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is a class of anticoagulant medications. They are used in the prevention of blood clots and, in the treatment of venous thromboembolism, and the treatment of myocardial infarction.

Von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a blood glycoprotein that promotes hemostasis, specifically, platelet adhesion. It is deficient and/or defective in von Willebrand disease and is involved in many other diseases, including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, Heyde's syndrome, and possibly hemolytic–uremic syndrome. Increased plasma levels in many cardiovascular, neoplastic, metabolic, and connective tissue diseases are presumed to arise from adverse changes to the endothelium, and may predict an increased risk of thrombosis.

In medicine (hematology), bleeding diathesis is an unusual susceptibility to bleed (hemorrhage) mostly due to hypocoagulability, in turn caused by a coagulopathy. Therefore, this may result in the reduction of platelets being produced and leads to excessive bleeding. Several types of coagulopathy are distinguished, ranging from mild to lethal. Coagulopathy can be caused by thinning of the skin, such that the skin is weakened and is bruised easily and frequently without any trauma or injury to the body. Also, coagulopathy can be contributed by impaired wound healing or impaired clot formation.

Thromboelastography (TEG) is a method of testing the efficiency of blood coagulation. It is a test mainly used in surgery and anesthesiology, although increasingly used in resuscitations in emergency departments, intensive care units, and labor and delivery suites. More common tests of blood coagulation include prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) which measure coagulation factor function, but TEG also can assess platelet function, clot strength, and fibrinolysis which these other tests cannot.

Congenital afibrinogenemia is a rare, genetically inherited blood fibrinogen disorder in which the blood does not clot normally due to the lack of fibrinogen, a blood protein necessary for coagulation. This disorder is autosomal recessive, meaning that two unaffected parents can have a child with the disorder. The lack of fibrinogen expresses itself with excessive and, at times, uncontrollable bleeding.

Hypoprothrombinemia is a rare blood disorder in which a deficiency in immunoreactive prothrombin, produced in the liver, results in an impaired blood clotting reaction, leading to an increased physiological risk for spontaneous bleeding. This condition can be observed in the gastrointestinal system, cranial vault, and superficial integumentary system, affecting both the male and female population. Prothrombin is a critical protein that is involved in the process of hemostasis, as well as illustrating procoagulant activities. This condition is characterized as an autosomal recessive inheritance congenital coagulation disorder affecting 1 per 2,000,000 of the population, worldwide, but is also attributed as acquired.

Bernard–Soulier syndrome (BSS) is a rare autosomal recessive bleeding disorder that is caused by a deficiency of the glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex (GPIb-IX-V), the receptor for von Willebrand factor. The incidence of BSS is estimated to be less than 1 case per million persons, based on cases reported from Europe, North America, and Japan. BSS is a giant platelet disorder, meaning that it is characterized by abnormally large platelets.

Ristocetin is a glycopeptide antibiotic, obtained from Amycolatopsis lurida, previously used to treat staphylococcal infections. It is no longer used clinically because it caused thrombocytopenia and platelet agglutination. It is now used solely to assay those functions in vitro in the diagnosis of conditions such as von Willebrand disease (vWD) and Bernard–Soulier syndrome. Platelet agglutination caused by ristocetin can occur only in the presence of von Willebrand factor multimers, so if ristocetin is added to blood lacking the factor, the platelets will not clump.

Venom-induced consumption coagulopathy (VICC) is a medical condition caused by the effects of some snake and caterpillar venoms on the blood. Important coagulation factors are activated by the specific serine proteases in the venom and as they become exhausted, coagulopathy develops. Symptoms are consistent with uncontrolled bleeding. Diagnosis is made using blood tests that assess clotting ability along with recent history of envenomation. Treatment generally involves pressure dressing, confirmatory blood testing, and antivenom administration.

Quebec platelet disorder (QPD) is a rare autosomal dominant bleeding disorder first described in a family from the province of Quebec, Canada. The disorder is characterized by large amounts of the fibrinolytic enzyme urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) in platelets. This causes accelerated fibrinolysis which can result in bleeding.

Clotting time is a general term for the time required for a sample of blood to form a clot, or, in medical terms, coagulate. The term "clotting time" is often used when referring to tests such as the prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time, activated clotting time (ACT), thrombin time (TT), or Reptilase time. These tests are coagulation studies performed to assess the natural clotting ability of a sample of blood. In a clinical setting, healthcare providers will order one of these tests to evaluate a patient's blood for any abnormalities in the time it takes for their blood to clot. Each test involves adding a specific substance to the blood and measuring the time until the blood forms fibrin which is one of the first signs of clotted blood. Each test points to a different component of the clotting sequence which is made up of coagulation factors that help form clots. Abnormal results could be due to a number of reasons including, but, not limited to, deficiency in clotting factors, dysfunction of clotting factors, blood-thinning medications, medication side-effects, platelet deficiency, inherited bleeding or clotting disorders, liver disease, or advanced illness resulting in a medical emergency known as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

The fibrinolysis system is responsible for removing blood clots. Hyperfibrinolysis describes a situation with markedly enhanced fibrinolytic activity, resulting in increased, sometimes catastrophic bleeding. Hyperfibrinolysis can be caused by acquired or congenital reasons. Among the congenital conditions for hyperfibrinolysis, deficiency of alpha-2-antiplasmin or plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) are very rare. The affected individuals show a hemophilia-like bleeding phenotype. Acquired hyperfibrinolysis is found in liver disease, in patients with severe trauma, during major surgical procedures, and other conditions. A special situation with temporarily enhanced fibrinolysis is thrombolytic therapy with drugs which activate plasminogen, e.g. for use in acute ischemic events or in patients with stroke. In patients with severe trauma, hyperfibrinolysis is associated with poor outcome. Moreover, hyperfibrinolysis may be associated with blood brain barrier impairment, a plasmin-dependent effect due to an increased generation of bradykinin.

Thromboelastometry (TEM), previously named rotational thromboelastography (ROTEG) or rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM), is an established viscoelastic method for hemostasis testing in whole blood. It is a modification of traditional thromboelastography (TEG).

References

- ↑ Alhaj, Dana; Hagedorn, Nikola; Cuntz, Franziska; Reschke, Madlen; Schuldes, Joerg; Ruthenberg, Juliane; Bakchoul, Tamam; Greinacher, Andreas; Holzhauer, Susanne (2024). "ISTH bleeding assessment tool and platelet function analyzer in children with mild inherited platelet function disorders". European Journal of Haematology. 113 (1): 54–65. doi: 10.1111/ejh.14198 . ISSN 0902-4441. PMID 38549165.

- ↑ American Society for Clinical Pathology, "Five Things Doctors and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation , American Society for Clinical Pathology, retrieved August 1, 2013, which cites

- Lehman, C. M.; Blaylock, R. C.; Alexander, D. P.; Rodgers, G. M. (2001). "Discontinuation of the bleeding time test without detectable adverse clinical impact". Clinical Chemistry. 47 (7): 1204–1211. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/47.7.1204 . PMID 11427450.

- Peterson, P.; Hayes, T. E.; Arkin, C. F.; Bovill, E. G.; Fairweather, R. B.; Rock Jr, W. A.; Triplett, D. A.; Brandt, J. T. (1998). "The preoperative bleeding time test lacks clinical benefit: College of American Pathologists' and American Society of Clinical Pathologists' position article". Archives of Surgery. 133 (2): 134–139. doi:10.1001/archsurg.133.2.134. PMID 9484723.

- Lind, S. E. (1991). "The bleeding time does not predict surgical bleeding". Blood. 77 (12): 2547–2552. doi: 10.1182/blood.V77.12.2547.2547 . PMID 2043759.

- ↑ Peterson, P.; Hayes, T. E.; Arkin, C. F.; Bovill, E. G.; Fairweather, R. B.; Rock Jr, W. A.; Triplett, D. A.; Brandt, J. T. (1998). "The preoperative bleeding time test lacks clinical benefit: College of American Pathologists' and American Society of Clinical Pathologists' position article". Archives of Surgery. 133 (2): 134–139. doi:10.1001/archsurg.133.2.134. PMID 9484723.

- ↑ Quiroga, T.; Goycoolea, M.; Muñoz, B.; Morales, M.; Aranda, E.; Panes, O.; Pereira, J.; Mezzano, D. (2004). "Template bleeding time and PFA-100® have low sensitivity to screen patients with hereditary mucocutaneous hemorrhages: comparative study in 148 patients". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2 (6): 892–898. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00693.x. PMID 15140124.

- ↑ Burns, E. R.; Lawrence, C. (1989). "Bleeding time. A guide to its diagnostic and clinical utility". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 113 (11): 1219–1224. ISSN 0003-9985. PMID 2535679.

- ↑ "Blood Chemistries". Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- 1 2 Dg, Dayyal (2016). "BLEEDING TIME (BT) AND CLOTTING TIME (CT)". BioScience. ISSN 2521-5760.

- ↑ Schafer, Andrew I.; Loscalzo, Joseph (2003). Thrombosis and hemorrhage. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 397. ISBN 978-0-7817-3066-2.

- 1 2 Mehic, Dino; Assinger, Alice; Gebhart, Johanna (2024-07-01). "Utility of Global Hemostatic Assays in Patients with Bleeding Disorders of Unknown Cause". Hämostaseologie (in German). doi:10.1055/a-2330-9112. ISSN 0720-9355. PMID 38950624.

- ↑ "Bleeding Time". Archived from the original on September 14, 2006. Retrieved 2009-01-02.