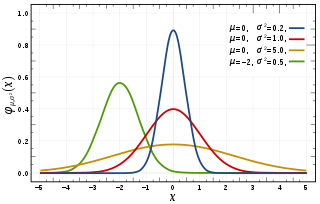

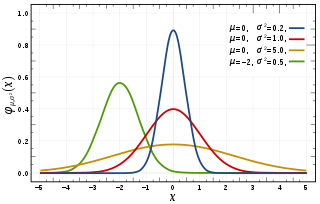

In probability theory and statistics, a normal distribution or Gaussian distribution is a type of continuous probability distribution for a real-valued random variable. The general form of its probability density function is

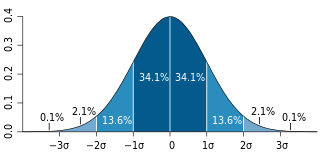

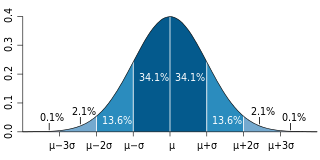

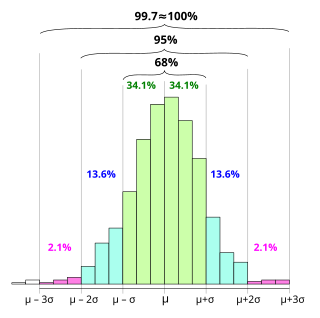

In statistics, the standard deviation is a measure of the amount of variation of the values of a variable about its mean. A low standard deviation indicates that the values tend to be close to the mean of the set, while a high standard deviation indicates that the values are spread out over a wider range. The standard deviation is commonly used in the determination of what constitutes an outlier and what does not. Standard deviation may be abbreviated SD or std dev, and is most commonly represented in mathematical texts and equations by the lowercase Greek letter σ (sigma), for the population standard deviation, or the Latin letter s, for the sample standard deviation.

In probability theory and statistics, variance is the expected value of the squared deviation from the mean of a random variable. The standard deviation (SD) is obtained as the square root of the variance. Variance is a measure of dispersion, meaning it is a measure of how far a set of numbers is spread out from their average value. It is the second central moment of a distribution, and the covariance of the random variable with itself, and it is often represented by , , , , or .

In probability theory, the central limit theorem (CLT) states that, under appropriate conditions, the distribution of a normalized version of the sample mean converges to a standard normal distribution. This holds even if the original variables themselves are not normally distributed. There are several versions of the CLT, each applying in the context of different conditions.

In probability theory, the law of large numbers (LLN) is a mathematical law that states that the average of the results obtained from a large number of independent random samples converges to the true value, if it exists. More formally, the LLN states that given a sample of independent and identically distributed values, the sample mean converges to the true mean.

In probability theory, Markov's inequality gives an upper bound on the probability that a non-negative random variable is greater than or equal to some positive constant. Markov's inequality is tight in the sense that for each chosen positive constant, there exists a random variable such that the inequality is in fact an equality.

In probability theory, the Vysochanskij–Petunin inequality gives a lower bound for the probability that a random variable with finite variance lies within a certain number of standard deviations of the variable's mean, or equivalently an upper bound for the probability that it lies further away. The sole restrictions on the distribution are that it be unimodal and have finite variance; here unimodal implies that it is a continuous probability distribution except at the mode, which may have a non-zero probability.

In probability theory and statistics, the generalized extreme value (GEV) distribution is a family of continuous probability distributions developed within extreme value theory to combine the Gumbel, Fréchet and Weibull families also known as type I, II and III extreme value distributions. By the extreme value theorem the GEV distribution is the only possible limit distribution of properly normalized maxima of a sequence of independent and identically distributed random variables. that a limit distribution needs to exist, which requires regularity conditions on the tail of the distribution. Despite this, the GEV distribution is often used as an approximation to model the maxima of long (finite) sequences of random variables.

In statistics, a consistent estimator or asymptotically consistent estimator is an estimator—a rule for computing estimates of a parameter θ0—having the property that as the number of data points used increases indefinitely, the resulting sequence of estimates converges in probability to θ0. This means that the distributions of the estimates become more and more concentrated near the true value of the parameter being estimated, so that the probability of the estimator being arbitrarily close to θ0 converges to one.

In probability theory and statistics, the continuous uniform distributions or rectangular distributions are a family of symmetric probability distributions. Such a distribution describes an experiment where there is an arbitrary outcome that lies between certain bounds. The bounds are defined by the parameters, and which are the minimum and maximum values. The interval can either be closed or open. Therefore, the distribution is often abbreviated where stands for uniform distribution. The difference between the bounds defines the interval length; all intervals of the same length on the distribution's support are equally probable. It is the maximum entropy probability distribution for a random variable under no constraint other than that it is contained in the distribution's support.

In statistics, the generalized Pareto distribution (GPD) is a family of continuous probability distributions. It is often used to model the tails of another distribution. It is specified by three parameters: location , scale , and shape . Sometimes it is specified by only scale and shape and sometimes only by its shape parameter. Some references give the shape parameter as .

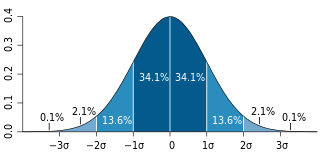

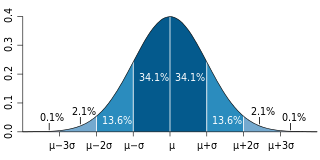

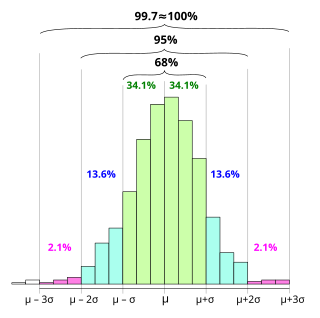

In statistics, the 68–95–99.7 rule, also known as the empirical rule, and sometimes abbreviated 3sr, is a shorthand used to remember the percentage of values that lie within an interval estimate in a normal distribution: approximately 68%, 95%, and 99.7% of the values lie within one, two, and three standard deviations of the mean, respectively.

In probability theory, the multidimensional Chebyshev's inequality is a generalization of Chebyshev's inequality, which puts a bound on the probability of the event that a random variable differs from its expected value by more than a specified amount.

In probability theory, Gauss's inequality gives an upper bound on the probability that a unimodal random variable lies more than any given distance from its mode.

In probability theory, Popoviciu's inequality, named after Tiberiu Popoviciu, is an upper bound on the variance σ2 of any bounded probability distribution. Let M and m be upper and lower bounds on the values of any random variable with a particular probability distribution. Then Popoviciu's inequality states:

In probability theory, concentration inequalities provide mathematical bounds on the probability of a random variable deviating from some value. The deviation or other function of the random variable can be thought of as a secondary random variable. The simplest example of the concentration of such a secondary random variable is the CDF of the first random variable which concentrates the probability to unity. If an analytic form of the CDF is available this provides a concentration equality that provides the exact probability of concentration. It is precisely when the CDF is difficult to calculate or even the exact form of the first random variable is unknown that the applicable concentration inequalities provide useful insight.

For certain applications in linear algebra, it is useful to know properties of the probability distribution of the largest eigenvalue of a finite sum of random matrices. Suppose is a finite sequence of random matrices. Analogous to the well-known Chernoff bound for sums of scalars, a bound on the following is sought for a given parameter t:

In statistics and probability theory, the nonparametric skew is a statistic occasionally used with random variables that take real values. It is a measure of the skewness of a random variable's distribution—that is, the distribution's tendency to "lean" to one side or the other of the mean. Its calculation does not require any knowledge of the form of the underlying distribution—hence the name nonparametric. It has some desirable properties: it is zero for any symmetric distribution; it is unaffected by a scale shift; and it reveals either left- or right-skewness equally well. In some statistical samples it has been shown to be less powerful than the usual measures of skewness in detecting departures of the population from normality.

In probability theory, Cantelli's inequality is an improved version of Chebyshev's inequality for one-sided tail bounds. The inequality states that, for

In probability theory, Eaton's inequality is a bound on the largest values of a linear combination of bounded random variables. This inequality was described in 1974 by Morris L. Eaton.