Related Research Articles

Xiphactinus is an extinct genus of large predatory marine ray-finned fish that lived during the late Albian to the late Maastrichtian. The genus grew up to 5–6 metres (16–20 ft) in length, and superficially resembled a gargantuan, fanged tarpon. It is a member of the extinct order Ichthyodectiformes, which represent close relatives of modern teleosts.

The Coon Creek Formation or Coon Creek Tongue is a geologic unit and Konservat-Lagerstätte located in western Tennessee and extreme northeast Mississippi. It is a sedimentary sandy marl deposit, Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) in age, about 70 million years old. The formation is renowned for its pristine fossils of Late Cretaceous marine invertebrates, including gastropods, bivalves, decapod crustaceans, and ammonites, particularly at Coon Creek in McNairy County, Tennessee, which the formation is named for. It is also known for producing fosslis of marine vertebrates, such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. Notable fossils from this formation is the gastropod Turritella, the bivalve Pterotrigonia thoracica, as well as other fossils such as crabs.

The Glen Rose Formation is a shallow marine to shoreline geological formation from the lower Cretaceous period exposed over a large area from South Central to North Central Texas. The formation is most widely known for the dinosaur footprints and trackways found in the Dinosaur Valley State Park near the town of Glen Rose, Texas, southwest of Fort Worth and at other localities in Central Texas.

The Urbión Group is a geological group in Castile and León and La Rioja, Spain whose strata date back to the Early Cretaceous (late Hauterivian to late Barremian. The formations of the group comprise a sequence of brown limestones in a matrix of black silt, sandstones, claystones and conglomerates deposited under terrestrial conditions, in alluvial fan and fluvial environments.

The Ripley Formation is a geological formation in North America found in the U.S. states of Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. The lithology is consistent throughout the layer. It consists mainly of glauconitic sandstone. It was formed by sediments deposited during the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous. It is a unit of the Selma Group and consists of the Cusseta Sand Member, McNairy Sand Member and an unnamed lower member. It has not been extensively studied by vertebrate paleontologists, due to a lack of accessible exposures. However, fossils have been unearthed including crocodile, hadrosaur, nodosaur, tyrannosaur, ornithomimid, dromaeosaur, and mosasaur remains have been recovered from the Ripley Formation.

Hypsibema missouriensis is a species of plant-eating dinosaur in the genus Hypsibema, and the state dinosaur of the U.S. state Missouri. One of the few official state dinosaurs, bones of the species were discovered in 1942, at what later became known as the Chronister Dinosaur Site near Glen Allen, Missouri. The remains of Hypsibema missouriensis at the site, which marked the first known discovery of dinosaur remains in Missouri, are the only ones to have ever been found. Although first thought to be a sauropod, later study determined that it was a hadrosaur, or "duck-billed" dinosaur, whose snouts bear likeness to ducks' bills. Some of the species' bones found at the Chronister Dinosaur Site are housed in Washington, D.C.'s Smithsonian Institution.

During most of the Late Cretaceous the eastern half of North America formed Appalachia, an island land mass separated from Laramidia to the west by the Western Interior Seaway. This seaway had split North America into two massive landmasses due to a multitude of factors such as tectonism and sea-level fluctuations for nearly 40 million years. The seaway eventually expanded, divided across the Dakotas, and by the end of the Cretaceous, it retreated towards the Gulf of Mexico and the Hudson Bay.

Paleontology in North Carolina refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of North Carolina. Fossils are common in North Carolina. According to author Rufus Johnson, "almost every major river and creek east of Interstate 95 has exposures where fossils can be found". The fossil record of North Carolina spans from Eocambrian remains that are 600 million years old, to the Pleistocene 10,000 years ago.

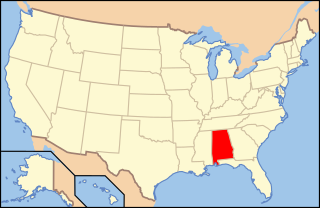

Paleontology in Alabama refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Alabama. Pennsylvanian plant fossils are common, especially around coal mines. During the early Paleozoic, Alabama was at least partially covered by a sea that would end up being home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and graptolites. During the Devonian the local seas deepened and local wildlife became scarce due to their decreasing oxygen levels.

Paleontology in Louisiana refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Louisiana. Outcrops of fossil-bearing sediments and sedimentary rocks within Louisiana are quite rare. In part, this is because Louisiana’s semi-humid climate results in the rapid weathering and erosion of any exposures and the growth of thick vegetation that conceal any fossil-bearing strata. In addition, Holocene alluvial sediments left behind by rivers like the Mississippi, Red, and Ouachita, as well as marsh deposits, cover about 55% of Louisiana and deeply bury local fossiliferous strata.

Paleontology in Arkansas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Arkansas. The fossil record of Arkansas spans from the Ordovician to the Eocene. Nearly all of the state's fossils have come from ancient invertebrate life. During the early Paleozoic, much of Arkansas was covered by seawater. This sea would come to be home to creatures including Archimedes, brachiopods, and conodonts. This sea would begin its withdrawal during the Carboniferous, and by the Permian the entire state was dry land. Terrestrial conditions continued into the Triassic, but during the Jurassic, another sea encroached into the state's southern half. During the Cretaceous the state was still covered by seawater and home to marine invertebrates such as Belemnitella. On land the state was home to long necked sauropod dinosaurs, who left behind footprints and ostrich dinosaurs such as Arkansaurus.

Paleontology in Missouri refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Missouri. The geologic column of Missouri spans all of geologic history from the Precambrian to present with the exception of the Permian, Triassic, and Jurassic. Brachiopods are probably the most common fossils in Missouri.

Paleontology in Iowa refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Iowa. The paleozoic fossil record of Iowa spans from the Cambrian to Mississippian. During the early Paleozoic Iowa was covered by a shallow sea that would later be home to creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, cephalopods, corals, fishes, and trilobites. Later in the Paleozoic, this sea left the state, but a new one covered Iowa during the early Mesozoic. As this sea began to withdraw a new subtropical coastal plain environment which was home to duck-billed dinosaurs spread across the state. Later this plain was submerged by the rise of the Western Interior Seaway, where plesiosaurs lived. The early Cenozoic is missing from the local rock record, but during the Ice Age evidence indicates that glaciers entered the state, which was home to mammoths and mastodons.

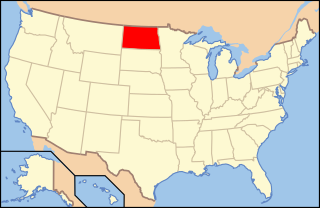

Paleontology in North Dakota refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of North Dakota. During the early Paleozoic era most of North Dakota was covered by a sea home to brachiopods, corals, and fishes. The sea briefly left during the Silurian, but soon returned, until once more starting to withdraw during the Permian. By the Triassic some areas of the state were still under shallow seawater, but others were dry and hot. During the Jurassic subtropical forests covered the state. North Dakota was always at least partially under seawater during the Cretaceous. On land Sequoia grew. Later in the Cenozoic the local seas dried up and were replaced by subtropical swamps. Climate gradually cooled until the Ice Age, when glaciers entered the area and mammoths and mastodons roamed the local woodlands.

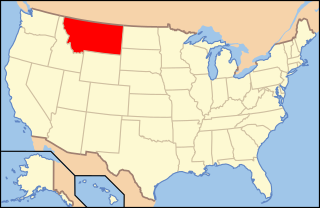

Paleontology in Montana refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Montana. The fossil record in Montana stretches all the way out to sea where local bacteria formed stromatolites and bottom-dwelling marine life left tracks on the sediment that would later fossilize. This sea remained in place during the early Paleozoic, although withdrew during the Silurian and Early Devonian, leaving a gap in the local rock record until its return. This sea was home to creatures including brachiopods, conodonts, crinoids, fish, and trilobites. During the Carboniferous the state was home to an unusual cartilaginous fish fauna. Later in the Paleozoic the sea began to withdraw, but with a brief return during the Permian.

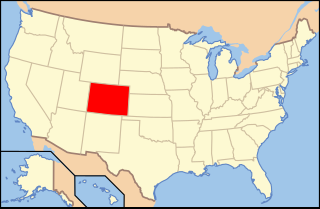

Paleontology in Colorado refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Colorado. The geologic column of Colorado spans about one third of Earth's history. Fossils can be found almost everywhere in the state but are not evenly distributed among all the ages of the state's rocks. During the early Paleozoic, Colorado was covered by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, conodonts, ostracoderms, sharks and trilobites. This sea withdrew from the state between the Silurian and early Devonian leaving a gap in the local rock record. It returned during the Carboniferous. Areas of the state not submerged were richly vegetated and inhabited by amphibians that left behind footprints that would later fossilize. During the Permian, the sea withdrew and alluvial fans and sand dunes spread across the state. Many trace fossils are known from these deposits.

Paleontology in New Mexico refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of New Mexico. The fossil record of New Mexico is exceptionally complete and spans almost the entire stratigraphic column. More than 3,300 different kinds of fossil organisms have been found in the state. More than 700 of these were new to science and more than 100 of those were type species for new genera. During the early Paleozoic, southern and western New Mexico were submerged by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, cartilaginous fishes, corals, graptolites, nautiloids, placoderms, and trilobites. During the Ordovician the state was home to algal reefs up to 300 feet high. During the Carboniferous, a richly vegetated island chain emerged from the local sea. Coral reefs formed in the state's seas while terrestrial regions of the state dried and were home to sand dunes. Local wildlife included Edaphosaurus, Ophiacodon, and Sphenacodon.

Paleontology in Alaska refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Alaska. During the Late Precambrian, Alaska was covered by a shallow sea that was home to stromatolite-forming bacteria. Alaska remained submerged into the Paleozoic era and the sea came to be home to creatures including ammonites, brachiopods, and reef-forming corals. An island chain formed in the eastern part of the state. Alaska remained covered in seawater during the Triassic and Jurassic. Local wildlife included ammonites, belemnites, bony fish and ichthyosaurs. Alaska was a more terrestrial environment during the Cretaceous, with a rich flora and dinosaur fauna.

The geology of South Dakota began to form more than 2.5 billion years ago in the Archean eon of the Precambrian. Igneous crystalline basement rock continued to emplace through the Proterozoic, interspersed with sediments and volcanic materials. Large limestone and shale deposits formed during the Paleozoic, during prevalent shallow marine conditions, followed by red beds during terrestrial conditions in the Triassic. The Western Interior Seaway flooded the region, creating vast shale, chalk and coal beds in the Cretaceous as the Laramide orogeny began to form the Rocky Mountains. The Black Hills were uplifted in the early Cenozoic, followed by long-running periods of erosion, sediment deposition and volcanic ash fall, forming the Badlands and storing marine and mammal fossils. Much of the state's landscape was reworked during several phases of glaciation in the Pleistocene. South Dakota has extensive mineral resources in the Black Hills and some oil and gas extraction in the Williston Basin. The Homestake Mine, active until 2002, was a major gold mine that reached up to 8000 feet underground and is now used for dark matter and neutrino research.

The Kristianstad Basin is a Cretaceous-age structural basin and geological formation in northeastern Skåne, the southernmost province of Sweden. The basin extends from Hanöbukten, a bay in the Baltic Sea, in the east to the town of Hässleholm in the west and ends with the two horsts Linderödsåsen and Nävlingeåsen in the south. The basin's northern boundary is more diffuse and there are several outlying portions of Cretaceous-age sediments. During the Cretaceous, the region was a shallow subtropical to temperate inland sea and archipelago.

References

- 1 2 "Missouri State Dinosaur". e-ReferenceDesk. Web Marketing Services, Inc. LLC. 2010. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ↑ "The State Dinosaur". State Symbols of Missouri. Missouri Secretary of State . Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Powers, Marc (February 19, 2004). "A bone to pick for Missouri". Southeast Missourian. Southeast Missourian. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Missouri Dinosaur Story". Bollinger County Museum of Natural History. 2010. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gilmore, Charles Whitney; Stewart, Dan R. (January 1945). "A New Sauropod Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Missouri". Journal of Paleontology . 19 (1). Society for Sedimentary Geology: 23–29. JSTOR 1299165.

- ↑ "Dinosaurs". Bollinger County Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

- ↑ Brownstein, Chase (2018). "The biogeography and ecology of the Cretaceous non-avian dinosaurs of Appalachia". Palaeontologia Electronica: 1–56. doi: 10.26879/801 . ISSN 1935-3952.

- ↑ Lindsey, Jason (November 25, 2006). "Missouri's ONLY Dinosaur". KFVS12. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- 1 2 Darrough, Guy; Fix, Michael; Parris, David; Granstaff, Barbara (September 2005). "Abstracts of Papers". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (3). Taylor & Francis: 49A–50A. Bibcode:2005JVPal..25S...1.. doi:10.1080/02724634.2005.10009942. JSTOR 4524499. S2CID 220413556.

- 1 2 Hale-Davis, Candice (March 15, 2008). "Dinosaur replica unveiled at Bollinger County museum". Southeast Missourian . Southeast Missourian. Archived from the original on March 8, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Fix, Michael F.; Darrough, Guy (2004). "Dinosauria and associated vertebrate fauna of the Late Cretaceous Chronister site of southeast Missouri". Abstracts with Programs. 36 (3). Geological Society of America: 14. Archived from the original on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- 1 2 Holloway, Brad (January 31, 2005). "Rock of ages – Museum reveals fossil find in Bollinger County". Southeast Missourian. Southeast Missourian. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Hypsibema". DinoChecker. January 8, 2011. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ↑ "The Chronister Dinosaur: Parrosaurus missouriensis". University of Minnesota. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoffman, David; Stinchcomb, Bruce L.; Palmer, James R., eds. (October 6–7, 2006). Field Trip 1: Chronister Mesozoic Vertebrate Fossil Site Bollinger County, Missouri (PDF). Association of Missouri Geologists. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Powers, Marc (July 11, 2004). "Holden signs state dinosaur bill". The Daily Dunkin Democrat. Daily Dunklin Democrat. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- ↑ "Missouri Dinosaur – Chronister Vertebrate Site – Bruce Sinchcomb". www.lakeneosho.org. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

This article needs additional or more specific categories .(June 2023) |