Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio, Latinized as Titianus, hence known in English as Titian, was an Italian (Venetian) Renaissance painter of Lombard origin, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno. During his lifetime he was often called da Cadore, 'from Cadore', taken from his native region.

Lorenzo Lotto was an Italian painter, draughtsman, and illustrator, traditionally placed in the Venetian school, though much of his career was spent in other north Italian cities. He painted mainly altarpieces, religious subjects and portraits. He was active during the High Renaissance and the first half of the Mannerist period, but his work maintained a generally similar High Renaissance style throughout his career, although his nervous and eccentric posings and distortions represented a transitional stage to the Florentine and Roman Mannerists.

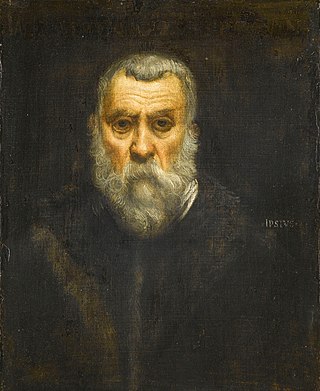

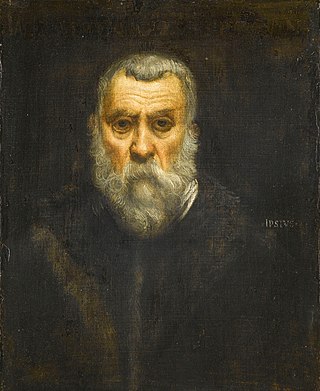

Jacopo Robusti, best known as Tintoretto, was an Italian painter identified with the Venetian school. His contemporaries both admired and criticized the speed with which he painted, and the unprecedented boldness of his brushwork. For his phenomenal energy in painting he was termed il Furioso. His work is characterised by his muscular figures, dramatic gestures and bold use of perspective, in the Mannerist style.

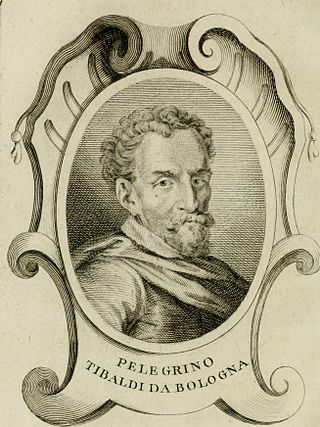

Pellegrino Tibaldi, also known as Pellegrino di Tibaldo de Pellegrini, was an Italian mannerist architect, sculptor, and mural painter.

The Annunciation is a painting by the Italian Renaissance master Titian, executed between 1559 and 1564. It remains in the church of San Salvador in Venice, for which it was commissioned.

The Pietà is one of the last paintings by the Italian master Titian, and in its final, extended state was left incomplete at his death in 1576, to be completed by Palma Giovane. Titian had intended it to hang over his grave, and the two stages of painting were to make it fit in two different churches. It is now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice.

Francesco Vecellio was a Venetian painter of the Italian Renaissance. He was the elder brother and close collaborator of the painter Tiziano Vecellio ("Titian").

The decade of the 1480s in art involved some significant events.

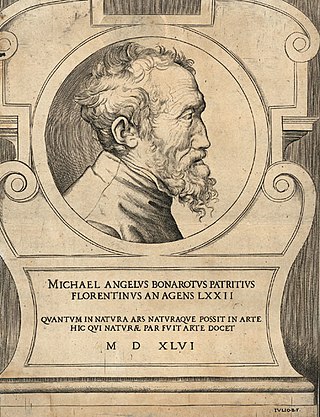

This article about the development of themes in Italian Renaissance painting is an extension to the article Italian Renaissance painting, for which it provides additional pictures with commentary. The works encompassed are from Giotto in the early 14th century to Michelangelo's Last Judgement of the 1530s.

The Madonna dell'Orto is a church in Venice, Italy, in the sestiere of Cannaregio. This was the home parish of Tintoretto and holds a number of his works as well as his tomb.

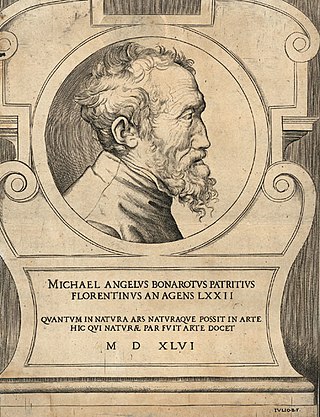

Giulio Bonasone was an Italian painter and engraver born in Bologna. He possibly studied painting under Lorenzo Sabbatini, and painted a Purgatory for the church of San Stefano, but all his paintings have been lost. He is better known as an engraver and is believed to have trained with Marcantonio Raimondi. He worked mainly in Mantua, Rome and Venice and with great success, producing etchings and engravings after the old masters and his own designs. He signed his plates B., I.B., Julio Bonaso, Julio Bonasone, Juli Bonasonis, Julio Bolognese Bonahso.

The Crowning with Thorns is a painting by the Italian Renaissance master Titian done during 1542 and 1543. It is housed in the Musée du Louvre in Paris, France.

The Entombment is a 1559 oil-on-canvas painting by the Venetian painter Titian, commissioned by Philip II of Spain. It depicts the burial of Jesus in a stone sarcophagus, which is decorated with depictions of Cain and Abel and the binding of Isaac. The painting measures 137 cm × 175 cm and is now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid. Titian made several other paintings depicting the same subject, including a similar version of 1572 given as a gift to Antonio Pérez and now also in the Prado, and an earlier version of c.1520 made for the Duke of Mantua and now in the Louvre.

The Penitent Magdalene is a 1560s oil painting by Titian of Saint Mary Magdalene, now in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia. The painting depicts Mary Magdalene who spent many years in the desert atoning for her sins The artwork was acquired from the Barbarigo Gallery in Venice, Italy and entered the Hermitage in 1850. Titian had kept this painting for himself and after his death Titian's son sold it along with other paintings to Cristoforo Barbarigo.

The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence is a Renaissance era oil painting by the Venetian artist Titian, dated from 1558. It depicts the Ancient Romans' murder of Saint Lawrence and was originally an altarpiece in the Church of Santa Maria Assunta dei Crociferi, although it is now in the church of I Gesuiti in Venice.

The Castello Roganzuolo Altarpiece, Castello Roganzuolo Polyptych or Madonna and Child with Saint Peter and Saint Paul is a painting by Titian, commissioned in 1543 by the leading citizens of Castello Roganzuolo, Province of Treviso, Veneto, Italy. It is now in the Albino Luciani Diocesan Museum in Vittorio Veneto.

Saint Sebastian, or Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian is an autograph work by the famed artist Doménikos Theotokópoulos, commonly known as El Greco. It shows the Martyred Saint in an atypical kneeling posture which has led some scholars to believe it to be a compositional quotation of various works by other great masters whom the artist admired. The painting is currently on display in the Palencia Cathedral.

Madonna and Child with Saint Catherine of Alexandria is a c.1550 oil on panel painting by the studio of Titian, now in the Galleria degli Uffizi. It was restored around the end of the 18th century, when the present carved and gilded frame was probably added.

Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap, also known as Man with a Red Cap, is an oil painting by the Venetian painter Titian, made in about 1516. It is part of the Frick Collection in New York City.