Tenochtitlan, also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, was a large Mexican altepetl in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear, but the date 13 March 1325 was chosen in 1925 to celebrate the 600th anniversary of the city. The city was built on an island in what was then Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico. The city was the capital of the expanding Aztec Empire in the 15th century until it was captured by the Tlaxcaltec and the Spanish in 1521.

The Aztecs were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec Empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427: Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Mexica or Tenochca, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although the term Aztecs is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era, as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821). The definitions of Aztec and Aztecs have long been the topic of scholarly discussion ever since German scientist Alexander von Humboldt established its common usage in the early 19th century.

Tezcatlipoca Classical Nahuatl: Tēzcatlipōca ) or Tezcatl Ipoca was a central deity in Aztec religion. He is associated with a variety of concepts, including the night sky, hurricanes, obsidian, and conflict. He was considered one of the four sons of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, the primordial dual deity. His main festival was Toxcatl, which, like most religious festivals of Aztec culture, involved human sacrifice.

Huitzilopochtli is the solar and war deity of sacrifice in Aztec religion. He was also the patron god of the Aztecs and their capital city, Tenochtitlan. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associating Huitzilopochtli with fire.

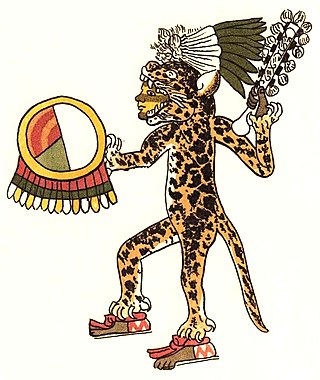

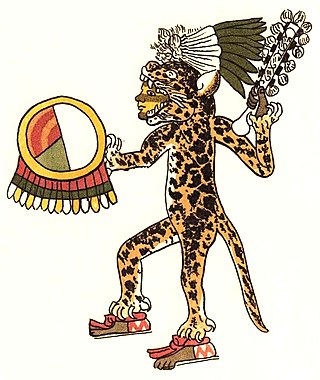

Jaguar warriors or jaguar knights, ocēlōtlNahuatl pronunciation:[oˈseːloːt͡ɬ] (singular) or ocēlōmeh (plural) were members of the Aztec military elite. They were a type of Aztec warrior called a cuāuhocēlōtl (derived from cuāuhtli and ocēlōtl. They were an elite military unit similar to the eagle warriors.

Aztec warfare concerns the aspects associated with the military conventions, forces, weaponry and strategic expansions conducted by the Late Postclassic Aztec civilizations of Mesoamerica, including particularly the military history of the Aztec Triple Alliance involving the city-states of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, Tlacopan and other allied polities of the central Mexican region. This united the Mexica, Apulteca, and Chichimeca people through marriages.

In pre-Columbian Aztec society, calpulli were units of commoner housing that had been split into kin-based or other land holding groups within Nahua city-states or altepetls. In Spanish sources, calpulli are termed parcialidades or barrios. The inhabitants of a calpul were collectively responsible for different organizational and religious tasks in relation to the larger altepetl. A calpul could be created based on an extended family, being part of a similar ethnic or national background, or having similar skills and tribute demands. The misunderstanding that calpulli were family units can be blamed on the fact that the word "family" refers to blood relations in English, while in Nahuatl it refers to the people whom you live with.

The Calmecac was a school for the sons of Aztec nobility in the Late Postclassic period of Mesoamerican history, where they would receive rigorous training in history, calendars, astronomy, religion, economy, law, ethics and warfare. The two main primary sources for information on the calmecac and telpochcalli are in Bernardino de Sahagún's Florentine Codex of the General History of the Things of New Spain and part 3 of the Codex Mendoza.

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of teotl was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature. The popular religion tended to embrace the mythological and polytheistic aspects, and the Aztec Empire's state religion sponsored both the monism of the upper classes and the popular heterodoxies.

Aztec society was a highly complex and stratified society that developed among the Aztecs of central Mexico in the centuries prior to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, and which was built on the cultural foundations of the larger region of Mesoamerica. Politically, the society was organized into independent city-states, called altepetls, composed of smaller divisions (calpulli), which were again usually composed of one or more extended kinship groups. Socially, the society depended on a rather strict division between nobles and free commoners, both of which were themselves divided into elaborate hierarchies of social status, responsibilities, and power. Economically the society was dependent on agriculture, and also to a large extent on warfare. Other economically important factors were commerce, long-distance and local, and a high degree of trade specialization.

Slavery in the Aztec Empire and surrounding Mexica societies was widespread, with slaves known by the Nahuatl word, tlacotli. Slaves did not inherit their status; people were enslaved as a form of punishment, after capturing in war, or voluntarily to pay off debts. Within Mexica society, slaves constituted an important class.

Human sacrifice was common in many parts of Mesoamerica, so the rite was nothing new to the Aztecs when they arrived at the Valley of Mexico, nor was it something unique to pre-Columbian Mexico. Other Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Purépechas and Toltecs, and the Maya performed sacrifices as well and from archaeological evidence, it probably existed since the time of the Olmecs, and perhaps even throughout the early farming cultures of the region. However, the extent of human sacrifice is unknown among several Mesoamerican civilizations. What distinguished Aztec practice from Maya human sacrifice was the way in which it was embedded in everyday life.

Pochteca were professional, long-distance traveling merchants in the Aztec Empire. The trade or commerce was referred to as pochtecayotl. Within the empire, the pochteca performed three primary duties: market management, international trade, and acting as market intermediaries domestically. They were a small but important class as they not only facilitated commerce, but also communicated vital information across the empire and beyond its borders, and were often employed as spies due to their extensive travel and knowledge of the empire. There is one famous incident where a tribe declined rice from another tribe, beginning a long and bloody clan war. The pochteca are the subject of Book 9 of the Florentine Codex (1576), compiled by Bernardino de Sahagún.

Huitzilatzin was the first tlatoani (ruler) of the pre-Columbian altepetl of Huitzilopochco in the Valley of Mexico.

Aztec clothing was worn by the Aztec people and varied according to aspects such as social standing and gender. The garments worn by Aztecs were also worn by other pre-Columbian peoples of central Mexico who shared similar cultural characteristics. The strict sumptuary laws in Aztec society dictated the type of fiber, ornamentation, and manner of wear of Aztec clothing. Clothing and cloth were immensely significant in the culture.

In Aztec religion, Chantico is the deity reigning over the fires in the family hearth. She broke a fast by eating paprika with roasted fish, and was turned into a dog by Tonacatecuhtli as punishment. She was associated with the town of Xochimilco, stonecutters, as well as warriorship. Chantico was described in various Pre-Columbian and colonial codices.

The Atlantean figures are four anthropomorphic statues belonging to the Toltec culture in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. These figures are "massive statues of Toltec warriors". They take their post-Columbian name from the European tradition of similar Atlas or Atalante figures in classical architecture.

The Chīmalli or Aztec shield was the traditional defensive armament of the indigenous states of Mesoamerica. These shields varied in design and purpose. The Chīmalli was also used while wearing special headgear.

Tēlpochcalli, were centers where Aztec youth were educated, from age 15, to serve their community and for war. These youth schools were located in each district or calpulli.

Cuauhtinchan Archeological Zone or Malinalco Archeological Zone, located just west of the town center on a hill called Cerro de los Idolos, which rises 215 meters above the town. On its sides are a number of pre-Hispanic structures built on terraces built into the hill. The main structures are at the top. This is one of the most important Aztec sites and was discovered in 1933, and explored by José García Payón in 1935. The visible complex dates from the Aztec Empire but the site's use as a ceremonial center appears to be much older. The sanctuary complex was built from the mid 15th century to the beginnings of the 16th. To get to the Cerro de los Idolos one must climb 426 stairs up 125 meters. Along the stairway leading to the site, there are signs with area's history written in Spanish, English and Nahuatl. The site contains six buildings. The Cuauhcalli or House of the Eagles, which dates from 1501, is the main building, which is significant in that it is carved out of the hill itself. The building is in the shape of a truncated pyramid, built this way due to the lack of space on the hill. The monolithic Cuauhcalli has been compared to the Ellora in India, Petra on the shores of the Dead Sea and Abu Simbel in Egypt. This was a sanctuary for the Eagle Warriors for rites such as initiation. A thirteen-step staircase leading into this temple is flanked by side struts. and two feline sculptures that face the plaza in front. The Cuauhcalli consists of two rooms, one rectangular and the other circular, with an opening in the wall between the two. After being carved out of the rock, the walls and ceiling were covered in stucco and painted with murals, most of which are almost completely gone. In the upper part, the entrance is symbolized by the open jaws of a serpent, complete with fangs, eyes and a forked tongue, which was painted red. This upper portion is covered by a thatched roof of the grass the area is named for.