Related Research Articles

The Rivonia Trial was a trial that took place in apartheid-era South Africa between 9 October 1963 and 12 June 1964, after a group of anti-apartheid activists were arrested on Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia. The farm had been the secret location for meetings of uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the newly-formed armed wing of the African National Congress. The trial took place in Pretoria at the Palace of Justice and the Old Synagogue and led to the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada, Denis Goldberg, Raymond Mhlaba, Elias Motsoaledi, Andrew Mlangeni. Many were convicted of sabotage and sentenced to life.

Lewis John Collins was an Anglican priest who was active in several radical political movements in the United Kingdom.

Victoria Nonyamezelo Mxenge was a South African anti-apartheid activist; she was trained as a nurse and midwife, and later began practising law.

The Treason Trial was a trial in Johannesburg in which 156 people, including Nelson Mandela, were arrested in a raid and accused of treason in South Africa in 1956.

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) was a British organisation that was at the centre of the international movement opposing the South African apartheid system and supporting South Africa's non-white population who were oppressed by the policies of apartheid. The AAM changed its name to ACTSA: Action for Southern Africa in 1994, when South Africa achieved majority rule through free and fair elections, in which all races could vote.

Craig Michael Williamson, is a former officer in the South African Police, who was exposed as a spy and assassin for the Security Branch in 1980. Williamson was involved in a series of events involving state-sponsored terrorism. This included overseas bombings, burglaries, kidnappings, assassinations and propaganda during the apartheid era.

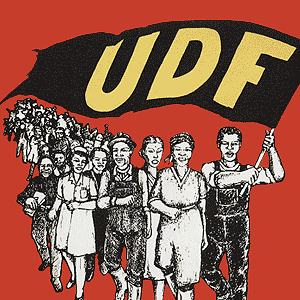

The United Democratic Front (UDF) was a South African popular front that existed from 1983 to 1991. The UDF comprised more than 400 public organizations including trade unions, students' unions, women's and parachurch organizations. The UDF's goal was to establish a "non-racial, united South Africa in which segregation is abolished and in which society is freed from institutional and systematic racism." Its slogan was "UDF Unites, Apartheid Divides." The Front was established in 1983 to oppose the introduction of the Tricameral Parliament by the white-dominated National Party government, and dissolved in 1991 during the early stages of the transition to democracy.

The Little Rivonia Trial was a South African apartheid-era court case in which several members of the armed resistance organization Umkhonto we Sizwe faced charges of sabotage. The accused were: Laloo Chiba, Dave Kitson, Mac Maharaj, John Matthews and Wilton Mkwayi. A confederate of theirs, Lionel Gay turned state witness, and in return, the prosecution dropped the charges against him.

Dame Diana Clavering Collins was an English activist and the wife of John Collins, a fiery canon of St Paul's Cathedral who earned an international reputation for his leadership of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the British campaign against apartheid in South Africa. She was his partner in these enterprises and in other activities.

Frederick John Harris was a South African schoolteacher and anti-apartheid campaigner who turned to terrorism and was executed after a bomb attack on a railway station. He was Chairman of SANROC, which in 1964 petitioned the International Olympic Committee to have South Africa excluded from the Olympics for fielding a white-only team. After being arrested for his political activities, he became a member of the African Resistance Movement (ARM).

Ronald Harrison was a South African artist most well known for his thought provoking 1962 painting Black Christ.

"I Am Prepared to Die" was a three-hour speech given by Nelson Mandela on 20 April 1964 from the dock at the Rivonia Trial. The speech is so titled because it ended with the words "it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die". It is considered one of the great speeches of the 20th century, and a key moment in the history of South African democracy.

During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

The Very Revd Gonville Aubie ffrench-Beytagh was an Anglican priest who served as the Dean of Johannesburg. He was also an anti-apartheid activist and was held in solitary confinement before going on trial for his activism.

Felicia, Lady Kentridge was a South African lawyer and anti-apartheid activist who co-founded the South African Legal Resources Centre (LRC) in 1979. The LRC represented black South Africans against the apartheid state and overturned numerous discriminatory laws; Kentridge was involved in some of the Centre's landmark legal cases. Kentridge and her husband, the prominent lawyer Sydney Kentridge, remained involved with the LRC after the end of apartheid, though they moved permanently to England in the 1980s. In her later years, Kentridge took up painting, and her son William Kentridge became a famous artist.

Alexander Hepple was a trade unionist, politician, anti-apartheid activist and author. He was the last leader of the South African Labour Party.

Phyllis Altman was a trade unionist and anti-apartheid activist in South Africa. Altman was an employee of the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU). She was also the general secretary of the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF), and a fiction writer.

Ethel de Keyser OBE OLG was a South African anti-apartheid activist based in London, England.

South Africa–Sweden relations refers to the bilateral relations between Sweden and South Africa. Formal relations between the two countries began with the opening of a South African legation in the 1930s with relations being upgraded to ambassadorial level in 1994 following South Africa's first non-racial democratic elections. In 2000 a South African - Swedish Binational Commission was established by President Thabo Mbeki and Prime Minister Göran Persson.

Winifred "Freda" May Levson was a South African activist. Levson fought against apartheid throughout her life. Her 1950 book, In Face of Fear: Michael Scott's Challenge to South Africa, brought public attention to the issues of racial segregation in Africa and also to the work of Reverend Michael Scott.

Christian Action, founded in 1946, was an inter-church movement dedicated to promoting Christian ideals in society at large.

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Herbstein, Denis (24 September 1999). "Phyllis Altman". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- 1 2 "Our Story". Canon Collins Educational & Legal Assistance Trust. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "The International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF)". South African History Online. 14 February 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ Interview with John Collins from the BBC documentary The World Against Apartheid: Have You Heard from Johannesburg? (Episode 1, "The Road to Resistance", at 14 minutes).

- 1 2 Herbstein 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ "No Easy Walk to Freedom: Nelson Mandela in the Archives - Senate House Library". www.senatehouselibrary.ac.uk.

- ↑ Herbstein 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ Herbstein 2004, pp. 103–104.

- 1 2 Herbstein 2004, p. 104.

- ↑ Herbstein 2004, p. 216.

Sources

- Herbstein, Denis (2004). White Lies: Canon Collins and the Secret War Against Apartheid. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 9780852558850.